Leprosy is an ancient horror. For millennia, people feared and shunned the ravaged bodies of lepers as “unclean.” A few dared to show compassion: St. Francis of Assisi famously kissed a leper for the sake of Jesus. But none ever charged headlong at the repulsive affliction with more Christian love and peasant gusto than Joseph de Veuster, who will be canonized as St. Damien of Molokai, “Apostle to the Lepers,” on October 11, 2009.

Leprosy is an ancient horror. For millennia, people feared and shunned the ravaged bodies of lepers as “unclean.” A few dared to show compassion: St. Francis of Assisi famously kissed a leper for the sake of Jesus. But none ever charged headlong at the repulsive affliction with more Christian love and peasant gusto than Joseph de Veuster, who will be canonized as St. Damien of Molokai, “Apostle to the Lepers,” on October 11, 2009.

Long known in Asia, leprosy had reached the Mediterranean world by the time of Christ. It became conspicuous in medieval Europe, prompting the founding of “lazar houses,” or refuges where doomed lepers could rot apart from “clean” folk. Common myths connected leprosy with lust: decaying flesh matched degenerate souls. By the 18th century, leprosy had mostly retreated to Scandinavia. Norwegian doctor G.H.A. Hansen first isolated the infectious agent, Mycobacterium leprae, in 1873. The medical term for leprosy is now “Hansen’s disease” in his honor.

As subsequent research would show, leprosy manifests itself in several categories of infection and with a range of symptoms. Slowly attacking the skin and mucous tissue, it can kill nerves, disable muscles, decalcify bones, and disfigure faces. Although a victim’s limbs and features do not actually fall off as they decay, he is left, in the words of historian Gavan Daws, “deformed, crippled, ulcerated, blinded, his senses devastated, his very ability to breathe threatened.” Contrary to age-old belief, leprosy is surprisingly hard to catch. It spreads by respiratory droplets or skin contact and only among the genetically susceptible.

Tragically, Hawaiians proved to be a susceptible population. Following their discovery by British explorer Captain James Cook in 1778, the Islands attracted sailors, traders, and settlers. Newcomers brought in foreign diseases, including smallpox, measles, syphilis, influenza, and leprosy, which devastated indigenous people. By the later 19th century, Hawaii’s native population had shrunk to about 20 percent of pre-contact levels. Within this remnant, 2 percent of people with full or part Hawaiian blood had leprosy. Extinction seemed inevitable. Natives (kanakas) blamed whites (haoles) for ruining their lives and culture.

White, mostly American, businessmen growing rich in the Islands took native mortality rates as evidence of racial inferiority. The prevalence of leprosy among locals reinforced puritanical contempt for Hawaiian morals. Old Testament strictures on lepers were used to justify strict segregation of the afflicted.

Elite attitudes reflected the Calvinism instilled by New England missionaries. The first of these had arrived in 1820 and quickly made important converts, including royalty. The French priests who came later were unwelcome. Although the king decreed religious toleration in 1839, Protestants and Catholics usually assumed the worst of each other in their competition for souls.

While the ministers’ descendants consolidated power, they tolerated native kings and queens as Westernized Christians. But in 1893 they overthrew the monarchy in favor of an American-dominated republic. Five years later the United States annexed Hawaii as a territory. Statehood would be granted in 1959.

Tangled threads of racism, imperialism, religious rivalry, and politics greatly complicated provisions for lepers, who were being forcibly isolated on the island of Molokai by a royal decree issued in 1865. Kanakas suspected the policy was part of a haole plot to kill even more of them. Some hid lepers from the authorities; some voluntarily accompanied infected loved ones into exile on Molokai as kokua (helpers), although this practice was prohibited after 1873. For Hawaiians, being removed from one’s family was worse than the disease itself.

Initially, the government Board of Health naively had expected the lepers to support themselves by farming. They were even supposed to build their own coffins. Officials begrudged every penny spent on provisions for Molokai. (Expenditures would come to consume 5 percent of the kingdom’s budget.) Lepers fought over scanty allotments of food and clothing. Those who still had some strength passed their time with sex, gambling, dancing, and home-brewed liquor. The weak lay untended in their huts until they perished. Despite the presence of superintendents and constables, Molokai was a land without law.

DAMIEN’S DESTINY

But as conditions deteriorated in the Islands, Providence was preparing a response. Hawaii’s first case of leprosy is said to have been confirmed in 1840. On January 3 of that year, Joseph de Veuster was born in a tiny farming village in Belgium. He was the seventh of eight children. Despite poverty, his childhood seems to have been happy. He was pulled out of school at age 13 to work on the family farm, but five years later his father sent him off for more education to prepare for a future dealing grain.

Although Flemish-speaking Joseph quickly learned French, the language of his new school, he was beginning to consider a quite different destiny. Two of his sisters had become Ursuline nuns and his older brother—now called Pamphile—had joined a French religious order, the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary and of Perpetual Adoration of the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar. Pamphile dissuaded Joseph from pursuing a vocation with the Trappists and helped him gain admission to the Sacred Hearts Fathers at Louvain. Joseph took the habit as Brother Damien soon after his 19th birthday in 1859. Thanks to Pamphile’s tutelage in Latin, Damien convinced his superiors to allow him to study for the priesthood.

Unlike Pamphile, Damien was no scholar, but he compensated with sheer hard work. He was modest, amiable, and impulsive, yet quick to apologize. Damien grew to be stocky, of medium height, with curly black hair and dark eyes. He was near-sighted and wore glasses. What impressed everyone was his physical strength: an observer remarked on his “fine broad face glowing with health.” A deeper level shows in three spiritual keywords he carved into his desk—“Silence Recollection Prayer.”

St. Francis Xavier, Apostle of the East, had long been Damien’s model. A talk by a visiting missionary bishop focused his interest on Polynesia. He envied Pamphile’s selection for a team to serve in Hawaii, which the Sacred Hearts Fathers had first reached in 1827. But when Pamphile caught typhus ministering to victims of an epidemic in Louvain, Damien entreated the head of the Congregation to let him take his brother’s place. This was a bold move, especially since Damien was only in minor orders and not qualified for a mission post. To everyone’s astonishment, permission was granted.

Five months later, after sailing round the Horn, Damien and his Sacred Hearts brethren reached Honolulu on March 19, 1864. He was ordained to the priesthood that spring. His first assignment was a remote district on the “Big Island” of Hawaii. Although required to ride or walk hundreds of miles over rough terrain visiting his flock, Damien still found time to grow vegetables and build chapels. The stalwart young priest thrived on hard physical labor. His greatest burden was isolation. He rarely saw another priest and had to go without confession for long periods.

Damien liked the natives, though he regarded them as “children” and “savages.” He deplored their promiscuous habits and reliance on pagan healers. He learned their language and its Pidgin counterpart. In turn, the kanakas warmed to a haole who would join their feasts and share their food from a common pot.

“THE GIVEN GRAVE”

Then at Eastertime in 1873, Damien volunteered to serve the leper colony at Molokai. He sailed for his new post two hours later. He was just 33 years old, the traditional age of the Crucified Savior.

Nature could scarcely have designed a better spot to confine lepers than Kalaupapa promontory on the north coast of the island of Molokai. Sheer volcanic cliffs 2,000-4,000 feet high barricade four square miles of land that juts out like an arrow into crashing seas. Hawaiians called this site “the Given Grave.” Lepers were initially settled at Kalawao, on the east side of the peninsula. Because ships could not land at its stony beach, getting lepers and supplies ashore via small boats was exceedingly risky.

Damien arrived with nothing more than his breviary. For the first few weeks, he slept under a tree rather than take shelter with a leper. But soon he was embracing his “unclean” flock as easily and naturally as had his “clean” ones earlier. Touching lepers with bare hands—something white Protestant ministers refused to do on their rare visits—acknowledged victims’ humanity as nothing else could. To quote Gavan Daws again, Damien had embarked upon “a priesthood of worms, of ghastly sights and suffocating smells.”

Initially, Damien found the stench of leprous sores so vile, nausea nearly impaired his ability to say Mass. He took up smoking a pipe to cover hospital smells and the miasma of the cemetery beside his cottage. Besides visiting each sick person weekly, Damien built coffins and dug graves himself. He purchased a large cross for the cemetery and imported lumber to fence in his “fine garden of the dead.” There lepers’ corpses were spared the attentions of hungry pigs.

When Damien arrived, there were 749 persons at Kalawao, the great majority lepers. About a third was Catholic. He offered Masses for them every Sunday in tiny St. Philomena’s Church. Sometimes he climbed the barrier cliffs to serve the “topside” residents who were not lepers. Not surprisingly, his zeal rapidly won converts. An infected kanaka minister complained to fellow Protestants in Honolulu about the priest’s “diabolical” influence. Damien described his approach as simply trying “to raise the courage of my patients. I present death to them as the end of their ills, if they will make a sincere conversion.”

Besides founding separate pious associations for men, women, and children, he also instituted perpetual Eucharistic adoration. Although Damien could do little to stop what he termed “disrespect paid to the moral law,” he did at times scatter noisy revelers with his stout stick.

In addition to his spiritual duties, Damien built houses, churches, a road, and an orphanage. He bandaged sores, dispensed medicine, and raised chickens. A longtime inmate of Kalawao summed up Damien as [original spelling intact]: “a vigorous, forceful, impellant man with a generous heart in the prime of life and a jack of all trades, carpenter, mason, baker, farmer, Medico and nurse, no lazy bone in the make up of his manhood, busy from morning to nightfall.”

Even Damien bent under this burden and fell into “black thoughts,” especially because he missed the opportunity for regular confession. (At one point he had to shout his sins—in French—at a priest aboard a ship that was not permitted to land at the settlement.) He begged his superiors to send another priest but those who came were sources of conflict rather than camaraderie. Damien was so at odds with one colleague that the two seldom spoke outside the confessional.

Much as Damien’s superiors acknowledged his good works at Molokai, they found his zeal “indiscreet” and certainly not saintly. His rule-bending was frustrating, his unwitting attraction of publicity an embarrassment. He has “no common sense and is ill-bred,” his exasperated vice-provincial complained. His bishop called him “over-animated and tempestuous.” At least, his sketchy notions of hygiene and housekeeping were beneath their notice.

In 1881, the king awarded Damien the cross of a Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalakaua. Another cross was already being impressed upon his flesh—leprosy. Damien had gone from “the perfection of youthful health and vigor” to faint early symptoms of the disease within three years of his arrival at Kalawao. By the early 1880s, he was limping from sciatic pain and had lost feeling in one foot. By 1885, the diagnosis was definite. That year, leprous growths had begun to invade Damien’s face. His death sentence was now posted for anyone to see. Two physicians examined Damien at this time to verify that he had no other diseases, to forestall future rumors of syphilis.

Although Damien had tried to shield his family from the truth, his condition became known worldwide early in 1886. The shock of learning this from a Belgian newspaper killed his 83-year-old mother.

Damien embraced his cross willingly. He would not have to carry it alone. As his superiors grew more irritable, helpers arrived from other quarters. The first of these was Joseph Ira Barnes Dutton, a Vermont-born veteran of the Civil War who had served with distinction as a quartermaster. Afterwards, he had worked for the Army in graves registration and personally supervised the disinterment of 6,000 Union corpses. Hitting bottom after a disastrous marriage and heavy drinking, Dutton converted to Catholicism in 1883, taking the baptismal name Joseph, which he used ever after.

He then spent two years testing a vocation with the Trappists of Gethsemani Abbey, but did not fit in. A newspaper story about Molokai inspired Dutton to volunteer there. Arriving in the summer of 1886, “Brother Joseph” immediately became indispensable. His calm, methodical disposition complemented Damien’s impulsiveness. He stayed at Molokai for more than 40 years as “brother to everybody” and director of the orphanage for leper boys. Near the end of his life he wrote: “I am an old, old relic, still on duty and happy. Almost ashamed to say how jolly I am.” Only when his remarkable strength collapsed did Brother Joseph leave the place he called “Molokai the Blessed.” He died in Honolulu in 1931 but was brought home to rest among his lepers.

Father Louis-Lambert Conrady, a French-speaking Belgian priest, appeared out of nowhere in 1888. Although Damien appreciated his company, others found him obnoxious. Conrady and Dutton later joined the Franciscan Third Order to mollify Damien’s suspicious superiors. Conrady went on to work at a leper hospital in China, where he died in 1914.

The year of 1888 also brought three Franciscan sisters and their chaplain to Molokai to run a new home for leper girls at Kalaupapa, about three miles west of Damien’s settlement. Their leader was Mother Marianne Cope, born Barbara Koob in Hesse-Darmstadt, Germany in 1838. Brought to Utica, New York as a toddler, she had worked in a woolen factory for nine years before joining the Franciscans of Syracuse in 1862.

At first Sister Marianne taught school, but she soon became nurse-administrator of the Franciscans’ hospital in Syracuse, which had an affiliated medical school. Her hospital introduced new standards of cleanliness developed abroad and admitted patients without regard for creed or color—daring policies at the time. She was elected Provincial Superior of her order seven years before answering a call to Hawaii in 1883.

With six companions, Mother Marianne transformed the vile receiving station for lepers in Honolulu into a place of peace and order. Under royal patronage, she also established an orphanage for the healthy children of lepers in the capital before proceeding to Molokai. Beautiful, serene, diplomatic, and unfailingly cheerful, her reception in the Islands was far smoother than Damien’s.

But Mother Marianne endured her own special crosses. Two of her original companions quickly succumbed to tuberculosis and she also contracted the disease. One sister went mad from the strain of the work. Mother Marianne’s oddest challenge was politely deflecting the Board of Health Director’s infatuated attentions. Mother Marianne stayed at Kalaupapa until she died in 1918, painfully afflicted with arthritis and dropsy. She was beatified in 2005.

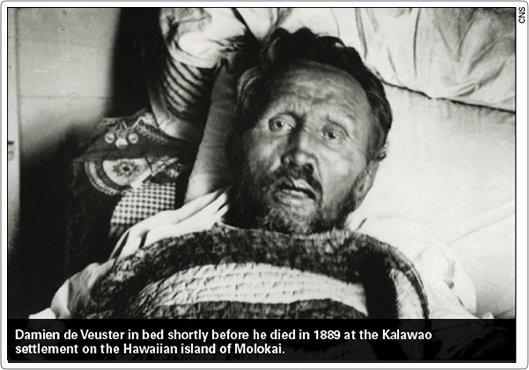

Thankful for new hands to carry on his work, Damien would not let go until his own deformed hands could no longer hold a chalice or a tool. Leprosy had disfigured his face, ravaged his body, and reduced his voice to a rasp, but he had finished the course and kept the faith. Damien died just before Easter on April 15, 1889 and was buried with his lepers, under the same tree he had slept beneath on arrival 16 years earlier.

Damien’s heroism awed the world—with one notable exception. Newspapers published a letter by white Hawaiian minister Dr. Henry Hyde which denounced Damien as a “coarse, dirty man, headstrong and bigoted” who had caught leprosy through fornication. Robert Louis Stevenson, himself dying of tuberculosis, defended Damien’s character in an open letter to Hyde with such white-hot fury that history remembers Hyde only as a footnote to Damien’s story.

Admirers had romanticized Damien even before he died. Afterwards the flood of donations and tributes included a granite commemorative cross funded by leading Englishmen, among them the Prince of Wales. Damien’s exploits were exaggerated. Sentimentality crept in. Biographer Gavan Daws insists that Damien addressed his Molokai parishioners as “we lepers” from the beginning and not, as legend would have it, to announce his own disease.

Damien’s superiors, however, could not picture their difficult charge as a saint. (Compare the coolness of the original Catholic Encyclopedia’s entry on Damien composed by one of them with the article on Molokai written by Joseph Dutton.) The flourishing Sacred Hearts Fathers did little to promote his canonization cause until 1938, when his generation of superiors was dead. Two years earlier, the Belgian government had removed Damien’s body for reburial with full honors at Louvain. Only his right hand remains at Kalawao.

World interest in Damien continued to grow even as the Hawaiian leprosy epidemic shrank after his death. Although leprosy has been fully curable with antibiotics since 1981, two to three million people worldwide have been disabled by the disease, which remains endemic in East Africa, Brazil, India, and Southeast Asia. The emergence of HIV as a global threat has expanded Damien’s relevance. AIDS sufferers have adopted Blessed Damien as their de facto patron.

Damien’s statue—branded with leprosy marks—stands in Honolulu and in the rotunda of the US Capitol. After his intercession healed a nun’s chronic intestinal disorder, he was beatified in 1994 and assigned May 10 as his feast day. The miracle permitting his canonization—the cure of a Hawaiian woman’s metastasized cancer—was approved in 2008. On October 11, at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Pope Benedict XVI canonized Damien, saying the new saint “teaches us to choose the good fight—not those that lead to division, but those that gather us together in unity.”

With canonization, the Church now recognizes what Stevenson said more than a century ago: the headstrong Apostle to the Lepers shared “all the grime and paltriness of mankind” yet was “a saint and a hero all the more for that.”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.