A devoted listener of the music of Sufjan Stevens never has to worry that a new album from the Michigan-born, Brooklyn-based singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist will sound just like the previous album. You can expect, without fail, his releases to be intricately composed. Most surprising are his stylistic variances, as in the case of Age of Adz (2010) an album showcasing a colossal, apocalyptic-like electronic feast and which, I must admit, made me long for the musical sways of his earlier works Greetings from Michigan (2003)and Seven Swans (2004). However, this detour never swayed my loyalty as a fan, convinced as I have been for many years that Sufjan is one of the most brilliant songwriters of our time.

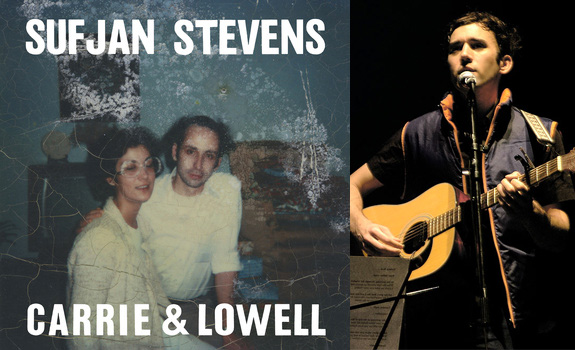

Stevens’ new release, Carrie & Lowell, is his most delicate and difficult offering to date, due to the subject matter that drove him to be the conduit for these songs. This collection is an exploratory guide to what grief demands of us. He admits the album was born from a terrifying inner place he entered after pain overwhelmed him following the death of his mother Carrie in 2012. Her life had been fraught with alcoholism, depression, and schizophrenia; their relationship was nearly nonexistant, marked by her leaving Stevens as a child. What ensued was a gaping distance and Sufjan’s longing to know her—a knowing that never arrived. He returned to Oregon to make parts of the record, the coastal state holding his only fading childhood memories of his mother.

The subject matter is truly grim, but Sufjan’s signature touch of genius is an ability to draw listeners into intimate places—terrifying places of loss and longing that may never be reconciled—and reveal them in exquisite ways. From start to end the songs are woven together with a thread of almost-whispered vocals, minimal production, and background room noise. Upon first listening you expect an eventual lift from the muffled vocals—a lift that never comes during the entire record, which after many listens to me feels just what grief is like: a pressing in, a weightedness, always there, never letting up.

A different take than the crisp sweetness of Seven Swans, and an obvious departure from the experimental waves of Age of Adz and the often whimsical feel of Come On, Feel the Illinoise (2006) Carrie & Lowell brings to mind the brazen honesty of Sufjan’s 2006 song “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.”, written in the same vein of gutsy vulnerability. Maybe it was a glimpse of what was to come, but even then a younger Stevens could not have predicted the darkness that would settle in these last few years.

Sufjan shows what makes good songwriting unbelievably great: the ability to experience immense heartache, sit in it, stay in it, to “mine the vein” so to speak, and then share how it was to live it and get through it.

The opening track “Death With Dignity” is an invitation to join Stevens in these places, in tenderness deeply delved. “Somewhere in the desert there’s a forest / And an acre before us / but I don’t know where to begin… I forgive you, mother, I can hear you / And I long to be near you / But every road leads to an end / …. You’ll never see us again”.

As on previous albums, there are elements of faith intertwined seamlessly into his writing, but this album is really more about the struggle and less about the triumph. Stevens portrays his distinct wrestling with God in the song “No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross” and a kind of broken yearning for Him in “John My Beloved”.

In “Fourth of July” he sings: “Did you get enough love, my little dove / Why do you cry? / And I’m sorry I left, but it was for the best / Though it never felt right”. One of the brightest moments on the album is “Should Have Known Better”, the darkness giving way to a widening musical lushness as he sings, “My brother had a daughter / The beauty that she brings, illumination”.

Stevens is a master at crafting such an intimate collection of songs without coming across as if he’s simply lifting from his personal journal, or overproducing songs that simply don’t need it. In his aged sensitivity as a songwriter he treats the songs as they deserve to be treated, as sparse and achingly beautiful pieces of music.

Too heavy a hand and these songs would lose their intricacy. Thankfully, working alongside brilliant engineers including Tucker Martine (The Decemberists, My Morning Jacket), these songs offer deep breaths of refreshing honesty woven together with perfect touches of light production. Only seven artists including Stevens are credited, a notable change from the ornate production of many previous recordings (often including instruments ranging from oboe and xylophone to “wood flute and likeminded whistles”).

Stevens has created a hauntingly beautiful soundtrack to the movie of real life, inviting us to pause and provoking us to really listen. And, as always, giving us music to take on our own paths of longing and grief, reflection and contemplation.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.