I was saddened to learn of James Hitchcock’s death on July 14th at the age of 87.

Like most people, my first encounter with the distinguished historian and author came through one of his books. Back in 1982, I submitted a report on his 1982 book, What Is Secular Humanism, for a theology assignment at my small Catholic high school in western Ohio. I no longer remember much about what I thought about the book at the time, but perusing its pages these many years later, I see that it displays Hitchcock’s trademark method: distilling extensive learning and profound ideas into crisp, clear prose accessible to a wide readership.

Hitchcock wasn’t afraid to tackle big, controversial topics. In that book, it was the principal malady troubling Western culture: the sundering of the connection between God and man—a reversal of the Incarnation. “As man more and more declares his independence from traditional moral and religious constraints,” he pointed out, “he does not soar to the heights of Nietzsche’s superman, but finds himself drawn down by his lower nature.” Created by “an all-wise and all-loving God, he cannot be truly free or truly happy except in loving obedience to his Creator’s will.”

Peering through the lens of history, Hitchcock devoted his life to the articulation of such foundational truths.

That life revolved around the city of St. Louis, where Hitchcock was born in 1938. He was a product of a pre-Vatican II Jesuit education, graduating successively from St. Louis University High School and Saint Louis University. Then came an East Coast hiatus: After obtaining a master’s and doctorate in history from Princeton University, he taught at St. John’s University in New York, where he met his wife, Helen, a convert to Catholicism. James and Helen Hull Hitchcock had four daughters and were married for almost 48 years until Helen’s death in November 2014.

In 1966, one year after the Second Vatican Council closed, he took a position in the history department at his alma mater. He would teach at Saint Louis University for more than forty years, emerging as one of the most incisive analysts of Church affairs during a turbulent period in American Catholic life.

Like Pope Benedict XVI and many other intellectuals who came of age in the mid-twentieth century, Hitchcock was a “liberal” by the standards of the pre-Vatican II Church, supporting causes such as liturgical reform, political and religious liberty, and intellectual and cultural engagement with the world. With Cardinal Ratzinger, he also perceived the theological, moral, and liturgical unmooring of so many Catholics from Tradition in the years following the council, and thus became known as “conservative.” Eschewing the role of detached scholar, he was an early combatant in what his longtime friend and ally, Msgr. George Kelly famously identified in his 1979 book as The Battle for the American Church.

Hitchcock’s name is all over the organizations and publications that championed orthodoxy in the bewildering decades of the ’70s and ’80s. He joined theologian Michael Novak and Notre Dame philosopher Ralph McInerny in their influential magazine, Crisis (founded in 1982 as Catholicism in Crisis), and was involved in starting the U.S. edition of the European theological journal Communio. He was, with McInerny and Msgr. Kelly, a founding member of the Fellowship of Catholic Scholars, an association formed in 1977, in the group’s own words, “to help the Catholic scholarly community better serve the teaching authority of the church in an era of dispiriting dissent.” In collaboration with his wife, who spearheaded the Adoremus Bulletin, Hitchcock promoted a return to liturgical sanity after the era of erratic experimentation that followed Vatican II.

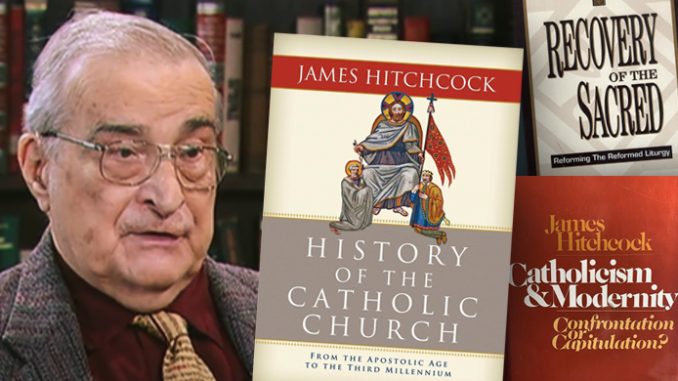

In all of this, Hitchcock, while sharply critical of theological modernism, never turned to anti-Vatican II traditionalism. Like Council participants John Paul II and Benedict XVI, he defended the actual teaching of the council against “interpreters” bent on distorting it to their own ends. The themes and trajectory of Hitchcock’s contributions to American Catholic discourse in these decades can be discerned from his book titles: The Decline and Fall of Radical Catholicism (1971); Catholicism and Modernity: Confrontation or Capitulation? (1979); The Dissenting Church (1983); Years of Crisis (1985); and The Recovery of the Sacred (1995).

With Decline and Fall, “a book which the author can sincerely say he wishes did not have to be written,” Hitchcock staked out his ground on the nature of reform in the Catholic Church, a question at the root of the theological confusion and controversy that characterized the decades following Vatican II. “Fundamentally,” he concluded, “in terms of the all-pervading spiritual revival which was expected to take place, renewal has obviously been a failure. Virtually everyone in the Church is now more uneasy, more suspicious, more apprehensive than before the Council. . . . Little in the Church seems entirely healthy or promising; everything seems vaguely sick and vaguely hollow.”

In response to the crisis, radicals offered only more change. “Many of the more prominent reformers insisted that they desired reform only in accordance with the traditions and authority of the Church,” Hitchcock noted, “when in reality they were already beginning to repudiate almost everything which was part of historic Roman Catholicism.”

At this early point in his career, Hitchcock judged that “the failure of aggiornamento must be about evenly apportioned between rigid reactionaries, especially in the hierarchy, who never believed in reform and did little to implement it, and radical innovators with little commitment to historic Catholicism who nonetheless had a disproportionate influence in the reform movement.” Yet, having counted himself among them, Hitchcock’s fire was directed chiefly at reformers, especially the “radicals” who “discredited the cause of reform precisely because they have made it appear to be a process of unending strife, instability, and abandonment of cherished beliefs.” Thus, Hitchcock reluctantly but ineluctably parted ways with many of his fellow “progressives.” Battle lines were being drawn.

On the strength of his publications, lecturing, and media presence, Hitchcock was by the 1990s a household name among informed, orthodox Catholics, which explains why my mother wrote to him as I neared my college graduation. My foolish heart was set on pursuing a doctorate in American history, and I was exploring Ivy League programs. Mom was worried about what might happen to her son’s faith should he be immersed in the “secular humanism” against which Hitchcock warned, so she wrote to the prominent historian for advice. He replied graciously to the unsolicited missive, and I still have the typescript letter with a blue ink signature. “I think that if he is a solid Catholic and is well-trained, it would not harm him to go to a secular graduate school,” he reassured the concerned mother. “Sometimes, of course, it requires courage and stamina to profess belief in a largely hostile environment.”

That was Hitchcock: clear, concise, and accurate.

Six years later, I wrote to Professor Hitchcock myself, this time to request input on the publication of my dissertation on American Catholic intellectual life in the twentieth century. He was again generous enough to write back, offering two pages of commentary and research references. He kindly provided a preface for that volume, my first book, released by an obscure academic press. (I suppose it must be the least-read Hitchcock piece ever published.) In commenting on the book’s thesis, he described the perennial dilemma at the heart of much of his own work: “Catholics both had to show themselves relevant to the culture and avoid the trap of merely accommodating themselves to that culture.”

I would finally meet Jim in person a year or two later at a Fellowship of Catholic Scholars (FCS) conference, which also provided the opportunity to speak with his comrades-in-arms Msgr. Kelly, Ralph McInerny, and others. Around the table at dinner, there was much complaining about the state of the Church and the world, but also plenty of ribbing and jocularity. They were happy warriors.

Although Hitchcock is more widely known as a participant in the intramural controversies of post-Vatican II Catholicism, his scholarly contributions in other areas should not be neglected. In my academic research, I have drawn on his informative two-volume treatment of The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life (Princeton University Press, 1995). In 2012, he published his final book, History of the Catholic Church—a sweeping ecclesiastical history that was an appropriate summation of a lifetime of study. I asked for and received it for Christmas. As a survey, it lacks some of the characteristic wit and verve of earlier writings, but it is nonetheless a testament to his magisterial mastery of Church history, and I continue to consult it as an authoritative reference.

The introduction to that volume contains many wise reflections on the craft of the Catholic historian. “The Catholic Church is the longest-enduring institution in the world, and her historical character is integral to her identity,” he began. “But an awareness of the historical character of the Church carries with it the danger that she will be seen as only a product of history, without a transcendent divine character.”

His treatment of the thorny problem of historical objectivity was similarly balanced. “Rather than historical ‘objectivity,’” he observed, “which implies personal detachment on the part of the scholar, the historian’s ideal ought to be honesty—an approach that is committed but strives to use evidence with scrupulous fairness.”

Sensitive to the particularities of time and place, Hitchcock nonetheless saw patterns in history, the drama of salvation that he believed was guided by Providence, no matter how messy it appeared. One of those patterns was the interplay between religion and culture. “Beginning with the Judaism of Jesus’ day, the Gospel has always had a disruptive effect on cultures,” he wrote. “If it did not, it would not be the Gospel, which requires fundamental conversion on the part of its hearers, does not allow them to remain part of their culture unchanged, and ultimately requires the transformation of culture itself.”

This passage, timeless in its historical application, also encapsulated Hitchcock’s assessment of his own country in the late twentieth century, when too many of his fellow Catholic intellectuals yielded too much ground to secular American culture.

Novak, Kelly, McInerny, and now Hitchcock have all gone to their eternal rewards. Fr. Joseph Fessio, S.J.—founder of Ignatius Press and another ally in the FCS—called his passing “the end of a dynasty.” In an interview with the National Catholic Register, Fessio remembered the Hitchcock home containing “an extensive personal archive” including “letters from concerned Catholics.” Perhaps Mom’s note is still there somewhere.

The “battle for the American Church” has evolved, and the lines of conflict are not identical to those of the 1970s, when James Hitchcock rose to prominence as a defender of the Faith. But the fundamental obligation remains the same: fidelity to Christ and his Church. As a serious and faithful historian, Hitchcock was a model and a mentor for many, including me.

Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

A lovely paean to a stalwart warrior.

Hitchcock’s view of the Vatican II controversies are particularly instructive, I would say.

The Church needs men who are sober, rational, honest — and, yes, resolutely Christian — to both record its history and help chart its course.

Wonderful article.

Next up: the Fessio interview.

“The Church needs men who are sober, rational, honest — and, yes, resolutely Christian — to both record its history and help chart its course.”

True, and yet when it comes to affirming the infallibility of Christ’s Magisterium that resides in The Deposit Of Faith that Christ Has Entrusted to His Church, For The Salvation Of Souls, Through Sacred Tradition, Sacred Scripture, And The Teaching Of The Magisterium, Ground In Sacred Tradition And Sacred Scripture, why is it, that when it comes to sexual morality, which serves out of respect for the Sanctity and Dignity of all beloved sons and daughters, that a Good man is often hard to find, when in Christ, we can know through both Faith and reason, that there does not exist , “a union of a private nature”, where “there is neither a third party, nor is society affected”, because we are Called to Holiness, and thus Called to be “Temples of The Holy Ghost”, in all our relationships.

Woe to us!

Yours truly first encountered Hitchcock when his “The Decline and Fall of Radical Catholicism (1971)” hit the shelves. But, here I would like to put his “patterns in history” under the microscope.

Three points:

FIRST, what “patterns”? Unlike paganism’s endless cycles of “history”—and given the fallenness of Man, the single pattern might have been “entropy” in all of its deformities. The Gordian Knot of original sin and, therefore, the tendency toward disorganization and disintegration. But propped up by one feeble scaffold or another to manage all of the scattered data points: whether in the historical Roman Empire, or the more ahistorical Caliphate, or pre-historical species Evolution-ism at the expense of specific butterflies and stuff, or now superhistorical AI as the “Cloud” if Unknowing, or even an antihistorical redefinition of “synods of bishops,” a process validated by an incestuous “synod-on-synodality” (say what?).

SECOND, the linear alternative to such a convoluted Gordian Knot is, as Hitchcock shows, the singular and “alarming” (Benedict’s term) Incarnation of the divine cutting directly into universal human “history”—as prefigured in the Old Testament and fulfilled in the New. Each Mass, now, as the “continuation and extension” of the one singular event (more than an idea or symbol!) of divine sacrificial love at a particular and historical time and place—on Calvary. The mystery of the sacramental Real Presence.

THIRD, Benedict gives a conceptual and equally moral clue: “Corresponding to the image of a monotheistic God is a monogamous marriage. Marriage based on exclusive and definitive love becomes the icon of the relationship between God and his people and vice versa, God’s way of loving becomes the measure of human love. This close connection between eros and marriage in the Bible has practically no equivalent in extra-biblical literature” (Pope Benedict, Deus est Caritas, 2006). The irreducibly particular, exclusive, and indissoluble marriage of one man to one woman.

So, history’s entropic mutations even include polyglot/polygamous Islamic family, or “ummah,” and, in the West, the equally sectarian and so-called LGBTQ “community” and their redefinition of “marriage” and the “family.” St. John Paul II was onto something particularly true in affirming the supremacy of “Veritatis Splendor” and of moral absolutes over the entropic “Fundamental Option, proportionalism, and consequentialism”…

SUMMARY: in step with Hitchcock, might we go so far as to say that St. Augustine, in the “City of God,” contrasted the love of God with “entropy”(!), aka love of the so-called “world”? In the coming decades what wisdom might we hear from the Augustinian Pope Leo XIV…probably not the entropic “who am I to judge.”

Kevin, I enjoyed this reflection on Jim Hitchcock very much. He was a sure and witty guide for this distressed Catholic in the late 1990s. Jim and Helen very kindly took me (and others) into their fold via Ralph McInerny’s Basics of Catholicism courses at Notre Dame where wannabe warriors were trained. Jim was the perfect mix of exacting professor and avuncular friend—he pushed me to read deeply in Church history. They turned out a platoon of marching professors, writers, journalists, doctors and lawyers who learned that only an understanding of Catholic history and a deep faith could sustain them for long battle ahead. It is the end of a dynasty. May Jim Hitchcock rest in peace, he was a good and faithful servant.