The late Cardinal Pell was a larger-than-life figure known for his outspoken orthodoxy and bluntness, as well as for being infamously jailed and then dramatically exonerated by the Australian courts.

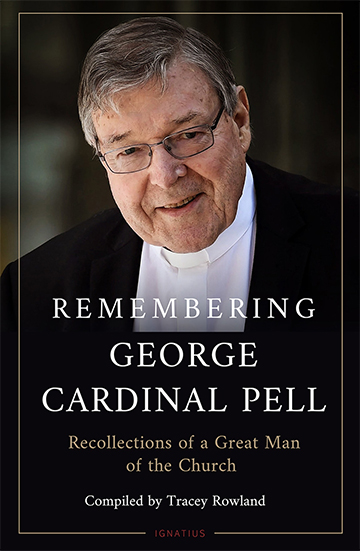

But what was Pell like among friends, colleagues, and those he interacted with in a wide array of private and public settings? Remembering George Cardinal Pell: Recollections of a Great Man of the Church, compiled by noted theologian Tracey Rowland and published recently by Ignatius Press, gathers over three dozen essays by laity, religious, priests, and bishops who knew Pell as a friend, mentor, shepherd, and co-worker.

Among the contributors are Cardinal Gerhard Müller, George Weigel, Joanna Bogle, Andrew Bolt, Bishop Peter Elliott, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, Sister Mary Grace, S.V., Canon Alexander Sherbrooke, Rev. Jerome Santamaria, and many more.

Tracey Rowland recently corresponded with CWR about her friendship with Cardinal Pell, and some of the insights and surprises found in this new book.

CWR: How did this book come about? With so many contributors, how did you pull it all together? What sort of criteria did you set?

Tracey Rowland: The idea for the book was suggested to me as we gathered around the Cardinal’s casket for the last time in the crypt of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney. I had been planning to collate a book of memoirs of people in Australian public life who were involved in student politics in the 1970s and 80s on the non-Marxist side of the battle. A friend suggested that before I collate a book about fighting undergraduate Marxists, I should compile a book of memories of Cardinal Pell.

When I approached Ignatius Press with the concept, the response was “Yes, but we don’t want a hagiography.” Ignatius did not want a submission to the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints. Rather, the idea was to gather a collection of memories from people who were close to the cardinal that would showcase different facets of his personality. I have used the metaphor of a kaleidoscope to describe it.

I drew up a list of people to invite, and I asked those on my list to suggest others. The process was worse than herding cats, though I must say that two of the biggest names–Cardinal Dolan and Cardinal Collins–were the most prompt to send in their entries.

I had only two criteria–that the person knew the cardinal well and that I could expect a contribution of a high literary level. I told contributors to imagine that they were writing a piece for the English weekly The Spectator.

CWR: For readers who are not Australian, could you give us a sense of the historical and cultural context of Cardinal Pell’s upbringing and eventual rise to being made a bishop and cardinal? Are there aspects of the Australian context that are especially important in understanding him, the various conflicts he went through, and (of course) his being sentenced, jailed, and then exonerated?

Rowland: I did add footnotes for international readers in circumstances where I thought that the cultural references would be lost on non-Australians. These were especially important for making sense of the many football stories and comments about something called “the Split”.

Cardinal Pell loved Australian Rules football. The memoir from his brother David tells the story of talent-spotters turning up to watch a young George Pell play in a school match with a view to recruiting him for their A-grade team.

It is hard to overestimate how big this game is in Victoria. To explain it to an American, I would say, imagine that in every suburb of Chicago there was a football team, and that every weekend for several months of the year almost every family in Chicago would have some member at a football match.

That a young George Pell could have been an A-grade Australian Rules footballer is one key to understanding his personality. Another is to understand that his father was a champion boxer.

The second difficult cultural reference for non-Australians is “the Split”. This expression refers to the division within the Australian Labor Party (ALP) in 1955. The short story is that Communist-controlled trade unions exercised a huge influence over some sections of the Australian Labor Party. This was more of a problem in the state of Victoria than in the state of New South Wales. In 1955, some members split from the ALP and formed the Democratic Labor Party (DLP). One effect of this was that the ALP did not win another federal election until 1972. Another effect was that the two great archdioceses of Sydney and Melbourne were also, in a sense, “split” along political lines. The Cardinal Archbishop of Sydney and Sydney Catholics in general continued to support the ALP. In Victoria, however, Archbishop Daniel Mannix, until his death in 1963, staunchly supported the DLP, as did many Victorian Catholics and Catholics in the mineral-rich state of Queensland. Just about every Victorian Catholic knows which side their grandparents or great-grandparents took in “the Split”. Cardinal Pell came from a DLP-supporting family.

A further factor for non-Australians to understand is that contemporary Victoria is, politically speaking, a bit like California. It’s the state where the culture wars are at their most intense, where the influence of cultural Marxism is strongest, and where the Catholic Church is politically weak, notwithstanding its significant size and wealth. Indeed, not only is the Catholic Church marginalised, but so too is the Liberal Party (the Australian analogue of the Republican Party).

Melbourne, the capital city of Victoria, was once described as ‘the jewel in the crown of the Liberal Party’, and it was the home of the most illustrious of the Liberal Party Prime Ministers–Sir Robert Menzies. However, this era ended with the social ascendancy of the generation of ’68 types and their rise through the institutions of government and education. During the COVID pandemic, the state of Victoria endured the longest lockdown in the entire world and the most oppressive legislation. Upon visiting Melbourne, one priest-friend, who is not an Australian, seriously suggested to me that the place needed an exorcist.

Many members of the social elite who run the state of Victoria hated Cardinal Pell and were delighted to have him behind bars. Whether or not it was in any way possible that he could have committed the crimes alleged was beside the point. He was a publicly outspoken intellectual enemy who needed to be contained. Those involved in financial corruption in Rome were also happy to have him contained, and yet others, ordinary members of the community who were scandalized by the extent of the child abuse problem, wanted someone in authority to pay for the negligence. As the most senior cleric in the country, the Cardinal was the obvious scapegoat. There was, in short, a perfect storm of factors at play. When the Cardinal was eventually vindicated, it was by the full bench of the Australian High Court, based in the national capital of Canberra.

Another Australian cultural reference is to biscuits. The word biscuit comes from the Latin bis (twice) and coctus (to cook), mediated through the old French word bescuit and finding itself as biscuit in Middle English. Americans, however, say cookie, which comes from the Dutch word koekje for a little cake. According to one of the contributors, the Cardinal was fond of mint slice biscuits.

CWR: How did you first come to meet and get to know Cardinal Pell?

Rowland: We met at a conference to celebrate 1000 years of Christianity in Ukraine. He was always interested in getting to know young Catholic scholars.

One of the strongest things about him was his understanding that lay Catholics need to be well-educated in their faith. He understood that if someone’s faith formation stopped at the end of primary school, there was not much hope for them successfully navigating themselves through the atheist landmines they would undoubtedly encounter at university.

Many of his projects were therefore about promoting Catholic intellectual life. I was one of those he encouraged to work in this field. We became co-patrons of the Australian Catholic Students’ Association.

CWR: Do you have a particular anecdote that stands out from your interactions with Cardinal Pell? How would you summarize his person and work?

Rowland: During his years in Rome, our paths would sometimes cross. One time, we ran into each other in the foyer of the hotel Santa Marta. He said something like, “Tracey dear, what are you doing here?” and after I explained, he said, “Well, I’m here to try to find a missing 20 million Euro”. This was during his time as Prefect for the Economy.

Although he was always dealing with weighty matters, he never appeared to be glum or despairing. That day in the foyer of hotel Santa Marta, he had an expression on his face like the cat emoji whose mouth curls around at the edge, signifying that something smells fishy. Others would have completely collapsed under the weight of the corruption he uncovered, but for him, it was just another day in a job he had been given by his “boss”.

He had an incredible capacity to remain optimistic and forge ahead regardless of the barriers or “bombs” raining down. He was courageous in an era when it is uncommon to find that quality in social leaders. Everyone knew where he stood on the hot-button issues, and everyone knew that he would never cave in to social pressure, especially to media pressure.

CWR: As you mentioned, you did not want works of hagiography. Are there weaknesses or struggles of Cardinal Pell that get mentioned?

Rowland: My contributors were not good at following the ‘no hagiography’ brief. They all admired him and wanted to convey that fact, though not in any mawkish way. They were also reluctant to say anything remotely critical when he had suffered so much. There were, however, a number of references to his sometimes colourful language. He was not shy about using expressions more commonly heard behind the bar of a pub than in the corridors of ecclesial institutions.

I think the copy editor was surprised by the number of times the word “bastard” appeared in the manuscript, and I had to assure her that for Australians, this noun can be a term of endearment. One famous example is that King Charles, when he was sent to board at Geelong Grammar in Victoria, was called a “pommy bastard” by his classmates. He knew when they called him that, that he had been accepted. No insult to his parents was intended.

CWR: The range of contributors is quite remarkable. What does that say about Cardinal Pell and his influence and relationships?

Rowland: He was interested in all kinds of people, especially couples who were building strong Catholic families, sporty types with a deep Catholic faith, Catholic politicians who were prepared to defend their faith in the public square, young people with religious vocations, and writers and scholars.

As a sociological generalisation, it could be said that younger Catholics, especially in Sydney and Melbourne, loved him, while the boomer generation found him to be an embarrassment–that is, someone who was stirring up anti-Catholic feeling by defending unfashionable theological causes. Since he was especially loved by the younger generations, I wanted the book to include memoirs from some of the young clergy for whom he was not just an ecclesial superior but a friend and father figure.

The generational difference can be explained by the fact that for the boomers the key issue was their social acceptance in a society dominated by Protestants, while for the younger generations who were born after 1968, in times that might be described as post-Christian or even anti-Christian, the key issue is Catholic identity and the courage to be a Catholic within a culture where this is not a ticket to upward social mobility.

Cardinal Pell offered clear and unequivocal teaching about what it means to be a Catholic, and he was prepared to take the social flak for this, as the younger generations of Catholics quickly learned in their university years would be their fate too, if they were to lift their heads above the parapet. The younger generations, however, have much less to lose than the boomers, who rode high on the waves of their tribal loyalties, excellent educations provided by holy religious institutions, and arrival in adult life just as the ecumenical movement was cracking glass ceilings.

A recent book by the Australian writer Philippa Martyr, titled The Future Catholic Church in Australia, does an excellent job of highlighting these generational differences.

CWR: Do you have favorite chapters or sections, or stories that surprised you?

Rowland: I was surprised to learn that he had trouble using mobile phones, computers, and washing machines. Anything related to IT and mechanical housework seemed to challenge him.

My two favorite anecdotes were from Cardinal Dolan and Fr. Greg Morgan. Cardinal Dolan recalled asking Cardinal Pell how he responded to people who accused him of acting like a “bull in a china shop”. Cardinal Pell replied: “Nonsense! I’m like a whole bloody rodeo in a china shop”!

Fr Greg Morgan’s story was about the Cardinal’s reaction to finding copies of books by Foucault, Derrida, and Heidegger on Morgan’s desk. Pell said, “Good Lord, Greg, [after reading those authors] can you still say grace, let alone Mass?”

I would give the prize for the theologically most insightful memoir to Justice Santamaria, for the most poignant reflection to Cardinal Collins, the prize for the memoir expressed in the most elegant literary style to Fr Anthony Robbie, and the prize for the memoir that best does justice to who George Pell was, on the stage of the world, to Tony Abbott.

The memoir from Sr. Mary Grace S. V. gave us a glimpse of his paternal tenderness which was a good counter-balance to all the football, rowing and boxing references and the memoirs from Joanna Bogle, Canon Alexander Sherbrooke and Bishop Peter Elliott threw light on his “at home in England” side, counter-balancing his Mannix-style Irish Catholicism that was on display in many of the other contributions.

Like in a kaleidoscope, where every facet of glass has its role in forming a symmetrical pattern, the different short essays reflect different shades of the personality of a man who was anything but one-dimensional.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply