At the start of the 1955 British film The Prisoner, a regal cardinal played by Alec Guinness finds Communist secret police waiting for him as he walks out of Mass in an anonymous Central European country.

Guinness, who would convert to Catholicism a year later and go on to play Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars, tells an attendant at the cathedral: “Try to remember, any confession I may be said to have made while in prison will be a lie, or the result of human weakness.”

In the taut psychological thriller, an interrogator played by Jack Hawkins (who would later portray Charlton Heston’s Roman patron in Ben Hur) slowly tortures the cardinal’s mind and body. He finally forces the priest to confess to “treason against the state” — the common charge that postwar Communists used to discredit heroic Catholic bishops who had fought the Nazis before them.

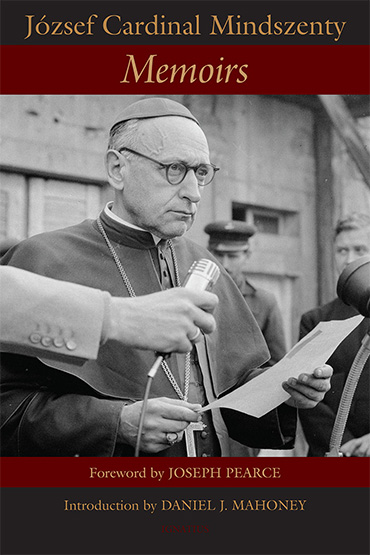

Nearly 70 years later, the memories of 20th-century Communist atrocities against the Catholic Church have nearly faded from living memory. But the new Ignatius Press edition of Hungarian Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty’s gripping Memoirs brings them back with all the vivid intensity of a fever dream.

The disgraced cardinal of The Prisoner was based on a composite of Mindszenty (1892-1975) and the Croatian Cardinal Aloysius Stepinac (1898–1960), two widely admired prelates who Communist authorities forced to confess to treason during show trials after World War II.

“The convict in solitary confinement never sees God’s green fields, woods, flowery meadows, acres of ripening grass scattered with poppies,” Cardinal Mindszenty writes in the English translation of his memoirs, recalling his 1949-1956 imprisonment on false charges of espionage.

In the name of the poor, the Communists of the mid-20th century sought to create a worker’s paradise as they created the Soviet bloc, but felt God stood in their way.

As they took over Catholic schools in Hungary, the new atheist authorities replaced crucifixes and pictures of the pope with photographs of Soviet leaders Vladimir Lenin and Josef Stalin.

Communist leaders quickly subdued Catholic bishops, including Mindszenty, who viewed their tyranny as simply a new variation on the Arrow Cross that they had resisted during World War II.

The Arrow Cross, or the Hungarian Nazi party, machine-gunned Jews on the banks of the Danube River as Soviet troops liberated Budapest from Adolf Hitler’s panzer divisions in 1944.

Confined in a solitary cell after the war, Mindszenty wrote that the guards jeered at him while he celebrated Mass, but that he ignored them.

In 1956, leaders of the Hungarian Revolution freed Mindszenty from his prison, allowing him to speak publicly as they declared their intention to leave the Soviet bloc.

Encouraged by the U.S. government under Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower to rise up, the Hungarians expected American troops to arrive and support them.

The Americans never came, but the Russian tanks rolled into Budapest 11 days later, crushing the revolutionary government and driving Cardinal Mindszenty into exile in the U.S. embassy.

“During the years between 1944 and October 23, 1956, Hungary had been a dungeon,” wrote Cardinal Mindszenty. “For eleven days (only four for me), we had been able to breathe freely. After November 4 the country became a prison once more.”

Granted political asylum, the cardinal lived in the U.S. embassy for the next 15 years, free to write but unable to participate in papal conclaves or leave the grounds.

Pope Paul VI eventually negotiated with Hungary to allow Mindszenty to leave the country on Sept. 28, 1971.

He continued to serve as the Catholic primate of Hungary in exile until 1973, when the pope accepted his retirement but refused to name a successor during his lifetime.

Cardinal Mindszenty spent his remaining years visiting exiled Hungarians in countries including Venezuela, Colombia, and the United States. He finally died at age 83 on May 6, 1975, in exile in Vienna, Austria.

Like many nations in Europe, Hungary went through several violent government changes during his lifetime. Hungarians endured the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, a brief Communist interlude after World War I, a restoration of the Kingdom of Hungary between the wars, a long Communist nightmare, and finally the current Republic of Hungary.

Hungary lost two-thirds of its borders and population in the Treaty of Trianon after World War I, when the winning side of the war carved Czechoslovakia out of the Habsburg domains.

Mindszenty lived through it all, steadfastly opposed to oppression in all its forms. He had St. Stephen of Hungary, St. Elizabeth of Hungary, and Our Lady of Mariapocs as his guides.

“The history of Bolshevism…shows that the Church simply cannot make any conciliatory gesture in the expectation that the regime will in return abandon its persecution of religion,” the exiled cardinal notes, referring to Communism.

Today, Communism continues to threaten religious freedoms in nations from Cuba to China. Socialist trends in nations like Venezuela have likewise destroyed faith, family, and freedom.

That makes the memoirs of Cardinal Mindszenty more relevant than ever, as a cautionary exhortation to resist those who persecute and kill in the name of the poor. They are the same poor who somehow do not disappear even after Communists and socialists redistribute the wealth of the pious.

As he prepared to leave the American embassy for exile in 1971, Cardinal Mindszenty wrote to Pope Paul VI that he had no regrets about his decisions. “I am convinced that even the greatest personal sacrifice shrinks to insignificance when the cause of God and his Church are at stake,” he writes.

After World War II, Hungarians coined a laconic phrase to describe their experiences of a century that began in hope and unfolded in death: “Temetni tudunk.” Loosely translated from the Finno-Ugric tongue of the Magyars, it means: “We know how to bury people.”

But another Hungarian phrase, even more ancient, has become common again since the peaceful 1989 fall of Communism in that nation.

They are words Hungarians prayed long before the remains of Cardinal Mindszenty returned to his homeland in 1991 for burial in consecrated ground at Esztergom, where Hungary’s kings lie entombed: “Szusz Mária, könyörögj érettünk.”

Hail Mary, pray for us.

Memoirs

By Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty

Introduction by Daniel Mahoney; Foreword by Joseph Pearce

Ignatius Press, 2023

Paperback, 477 pages

Related at CWR:

• “Cardinal Mindszenty and the recovery of heroic Christian virtue” (October 14, 2022) by Daniel J. Mahoney

• “Cardinal Mindszenty’s Memoirs are ‘deeply informative, moving, and spiritually and politically instructive’” (March 2, 2023) by Paul Senz

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

If only, the Wise One would whisper this in the ear of the modern prelates of our day….

“The history of Bolshevism…shows that the Church simply cannot make any conciliatory gesture in the expectation that the regime will in return abandon its persecution of religion,” the exiled cardinal notes, referring to Communism.

Today, 3 April 23, Crisis Magazine feature an excellent article by Fr Perricone “The Preferential Option for the ‘Poor Sinner’.” exposing the doctrinal change in the mission of the church from saving souls to redistribution of wealth.

That oppression is still with us, but it is cleverly disguised. We can NEVER forget that.

“The history of Bolshevism …. shows that the Church simply cannot make ANY (emphasis mine) conciliatory gesture in the expectation that the regime will in return abandon its persecution of religion.”

Could it be any clearer?