In the late 1530s, a Castilian priest recently arrived in New Spain encountered two indigenous students from the Franciscan College of Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, founded in 1536 near Mexico City, which locals still called Tenochtitlan. Unable to believe the stories he had heard about native scholars who spoke Latin like Cicero and could explicate the complexities of Catholic theology, the priest asked the students to recite the Pater Noster and the Credo. After the recitation, the priest objected to an apparent error the pair made in the latter, stating that the line was “nato ex Maria Virgine.” The boys asked the priest – in Latin – to identify the case of “nato” and he did not know. The two young native scholars then proceeded to dissect the prayer’s grammar, explaining how the line must be “natus ex Maria Virgine.”

As you might imagine, opposition existed in sixteenth-century Spain and New Spain to classically educating native peoples. Though the Franciscans had the support of the Crown when they founded their college in 1536 on the feast of the Epiphany – a date signaling a call to Gentiles to the true faith – opposition to the school ranged from concerns over a waste of mendicant resources to fear about producing native scholars better educated than most European colonists. The first classical school in the Americas, the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, offered to the sons of native nobles an education in the trivium – Latin grammar, rhetoric, and logic – and the quadrivium – arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. Its alumni not only taught at their alma mater and assisted other religious institutions, but also served their communities as native governors and officials. Some scholars argue that the Colegio was meant to be a seminary forming indigenous priests, but opposition prevented any ordinations.

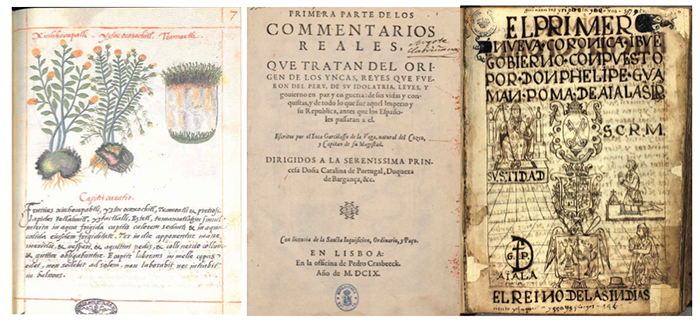

Though the Colegio would lose support and funding before the end of the century, the native scholars it produced continued to collaborate with their Franciscan teachers, co-publishing historical works, dictionaries, grammars, and devotional texts that today provide rich insight into the origins of Mexican Catholicism. During its early years, native students and teachers produced an illustrated Nahuatl-language herbal medicine text modeled after Early Modern European medical manuals, the first herbal and medical text produced in the New World. After preparing a Latin translation, the Colegio sent it to Spain in 1552 to garner institutional support and it eventually landed in the Vatican collections; in 1990, Pope St. John Paul II returned the original manuscript of the Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis to Mexico and it now resides in the National Institute of History and Anthropology in Mexico City.

The Colegio’s classically-educated students were so important to the evangelizing project that the famed Franciscan ethnographer and Nahuatlato (i.e., someone fluent in Nahuatl) fray Bernardino de Sahagún, who arrived to New Spain in 1529 and remained for 50 years, stated that if sermons in the native language were free of heresy and worth publication, it was because their tri-lingual native collaborators with their deep knowledge of Castilian, Nahuatl, and Latin had translated them. Sahagún himself would publish numerous texts with indigenous co-authors, the most famous being The Florentine Codex, a 12-volume compendium detailing the history, customs, knowledge, and religion of central Mexico shortly after Castilian invasion, and for which Sahagún interviewed indigenous elders. As a Mexican Catholic and a historian of colonial Mexico, these indigenous-Christian works – and associated memoirs by their Franciscan tutors – are some of my favorite texts, illustrating how native peoples made Catholicism their own.

Throughout the colonial period in Latin America (~1520s to 1820s), classical education retained an important presence, not simply for the European elite and independence leaders of the nineteenth century as one might expect, but also for native scholars over hundreds of years and well beyond Mexico’s borders. Many native communities in Latin America had an established intellectual tradition that predated Castilian arrival, and some indigenous intellectuals embraced European humanistic studies as their own. Indeed, the collaborative projects produced in 16th-century New Spain led to a Golden Age of indigenous intellectual accomplishments in the 17th century, with scholarly texts appearing into the late colonial period.

Several Golden Age indigenous intellectuals are well-known, such as nobleman and mestizo Garcilaso de la Vega el Inca who, influenced by Neoplatonists, argued in the early 17th century in Royal Commentaries of the Incas that some aspects of Inca sun worship approached an understanding of the “true” religion. Around 1615, Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, a descendant of Inca nobility, authored an epic history of Andean societies unfolding in four eras preceding the birth of Christ which he related alongside European history. In his account of Andean history, Guaman Poma’s contemporary, Joan Pachacuti Yamqui, identified in Inca beliefs and festivals an anticipation of Christianity. A mestizo born into privilege, don Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl composed Spanish-language indigenous histories in the mid-17th century, depicting Nezahualcoyotl, a native leader from Texcoco, as an idealized ruler who intuited the idea of one God before Christianity had reached Mexico’s shores.

At the turn of the 17th century, a Nahua (Aztec) author in Mexico City who called himself don Domingo de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin composed histories of the ancient Nahua past, a diary of Mexico City events, and his own Spanish-language version of a popular Conquest narrative penned by Hernando Cortés’ secretary, Francisco López de Gómara (who himself never visited the Americas). This book is the only known attempt by a native author to adapt and appropriate a Castilian text about the Americas. The late colonial period saw the production of Nahuatl and Quechua-language devotional dramas and passion plays influenced by European medieval miracle plays and baroque Spanish theater, with particular emphasis on the story of Guadalupe.

Scholarly interest in the historical roots of classical education in Latin America is growing. Of note is Antiquities and Classical Traditions in Latin America, a 2018 collection of essays exploring classical traditions generated from within Latin America during the colonial, independence, and modern periods. Editors observe that with some exceptions – i.e., David Lupher’s Romans in a New World: Classical Models in Sixteenth-Century Spanish America and Sabine MacCormack’s work examining Rome’s influence in colonial Peru – scholars have overlooked Latin America’s broader appropriations of Greco-Roman culture. (For a concise overview, see Anthropologist and Nahuatlato David Tavárez’s “Indigenous Intellectuals in Colonial Latin America”.)

Even as classical education is enjoying a historic pandemic-driven boom – and despite the historical roots of classical education in Latin America – resources for Spanish-speaking families remain limited. The Angelicum Academy, a Church-approved homeschooling program renowned for its online Socratic discussions, is seeking to change that. This fall, we are launching The Great Books Program en español, starting with Year 1: The Ancient Greeks. Beginning on Tuesday, October 4 (the feast of St. Francis), adults and students ages 14 and over will meet online once a week for two hours with me and other university professors for a Spanish-language discussion of important texts that shaped western civilization. Next fall we will add Year 2: The Ancient Romans.

As I develop Angelicum’s Great Books Program en español, I will be incorporating Spanish, Latin American, and indigenous-Christian texts into Year 3: The Middle Ages and Year 4: The Moderns. Together, students and I will explore the fusion of Platonic and Christian thinking in texts generated from within Latin America, building upon our Socratic discussions in Year 1 and Year 2. This is a rich opportunity to broaden student understanding of the classical tradition in their ancestral homelands, particularly as we draw in participants from around the Spanish-speaking world.

Discussing classical texts in Spanish means students and I will be reading many of the same texts that the sons of native nobles in Colonial Mexico studied (albeit in Latin) with their Franciscan tutors at the first classical school in the Americas. Far from introducing the classical tradition to Latin America and its descendants in the U.S., the Angelicum Academy is participating in a continuum of intellectual tradition, one whose historical reach predates European introduction of the humanities. As a Latin American historian specializing in the origins of Mexican Catholicism, I consider it a gift to develop and direct the Great Books Program en español for the Angelicum Academy. Indeed, as far as we know, our program – offering Socratic discussions online in Spanish – is the first of its kind.

The Angelicum Academy has, since the year 2000, provided an authentically Catholic homeschooling curriculum from Nursery School (age 3) to Associate’s degrees; its flexible programs include syllabi, study guides, lesson plans, grading, transcripts, and parental support, with live online Socratic discussions beginning in Grade 3. For high school students, we offer both a fully online curriculum that pairs recorded asynchronous lectures with subject-specific tutor support and an online Great Books Program that meets weekly with a pair of moderators for a live, two-hour discussion of classical texts. Students may earn and apply up to 75 college credits towards obtaining an A.A. degree by the end of 12th grade; some students earn a B.A. one year later. Online classes for our English-language programs begin September 1.

Please share news of the fall launch of our renowned Great Books Program in Spanish with your Spanish-speaking friends and contacts. For more information, enrollment forms, and an informative video in Spanish, please visit The Great Books Program en español.

We’ll see you online on October 4! ¡Nos vemos en línea el 4 de octubre!

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Fascinating and totally news to me!

1. Once upon a time, for a hundred or two hundred years or so, Catholic Spain was the greatest (most powerful) nation in the world. It has those vast colonies. It drove the Muslim conquerors out of Spain. It has lots of gold taken from the New World. It had a great navy.

2. But then something happened. Just what happened I do not know.

3. Protestant Britain and Catholic/Revolutionary France suppassed Spain. Spain lost most of its colonies to revolutionaries. In the end, it mainly just had Cuba and the Philippines, and then the USA took those away, too.

4. To me, the greatest subject of interest from the golden age of Spain is the writings of Catholic theologians wrestling with the issues of the military conquest and rule of the native non-Christian peoples in the Americans.

5. I know that in the present time many people in Latin American live lives that are comparable to the “good life” that many Americans live.

6. Yet, all in all, something seems to have really gone wrong in Latin America. In so many of those nations, the police, the courts, the military, tax collectors, and license-granting gov’t bureaucrats are extremely corrupt.

7. Plus, in part because of all this corruption, Marxist movements still seem to be pretty strong in Latin America.

8. A great books program in Spanish is a good idea. Bravo.

9. But I hope the past is not idealized. The golden age of Spain and the Spanish Empire had, I think, some terrible injustices and bad ideas, and I think those sowed seeds that are still today bringing forth a bad harvest.

Hello Veronica. I would love to have a list of your primary sources from Mexico. I would be willing to share mine. My list is pretty impressive, and includes Spanish and English translations. I have a 4 volume set of the writings of Zumarraga, the writings of Motolinia, much of Sahagun, the works of Junipero Serra, Cortés, Bernal Diaz and much more. I am going to buy some documents from Vasco de Quiroga as soon as I can. I can send you a list of my sources in my library. If I see your email address, I will send it now. Thank you.

I sent you the link via Facebook. Musings of a Mariner Sojourning in the Land of Woke is mine. You may like my articles I have written on there as well. We have a devotion to Isabel la Católica, and our library on her is equally amazing.