Rome, Italy, Nov 2, 2021 / 14:00 pm (CNA).

On one of Rome’s most important Renaissance-era streets lies a historic church dedicated to prayer for the dead, especially the poor and unknown.

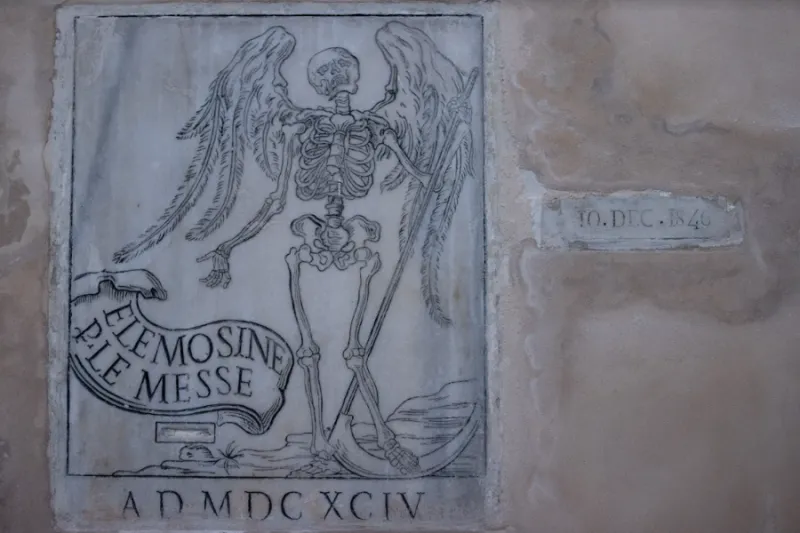

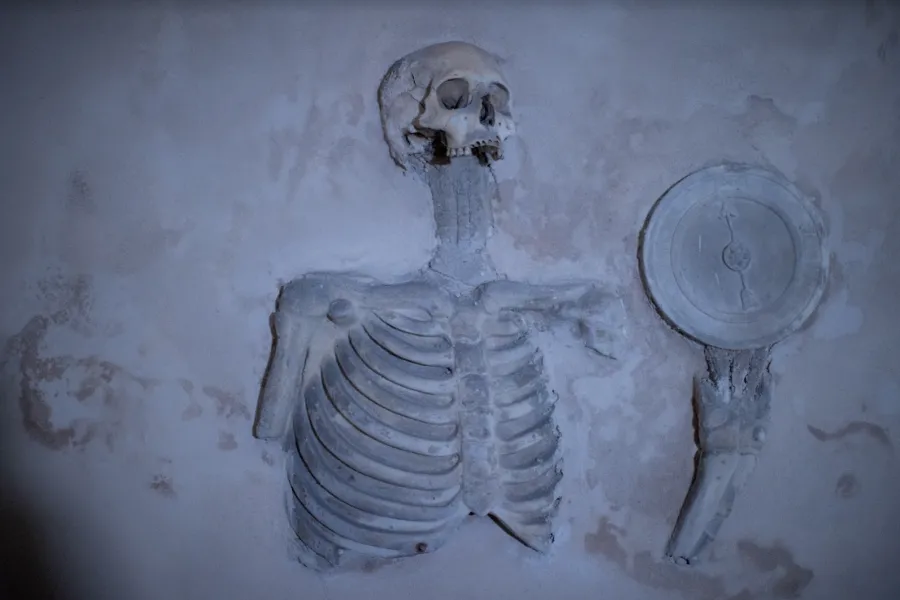

On the church’s facade can be found stone slabs with holes just large enough to slip coins into, decorated with images of winged skeletons holding a scythe or hourglass.

“Alms for the poor dead who are taken in the countryside” is written on one. “Alms for perpetual lamps in the cemetery” is written on another, and “alms for Masses” on yet another.

One winged skeleton reminds passersby of their mortality, as it holds a sign with the Latin phrase “Hodie mihi, cras tibi” (“Today me, tomorrow you.”)

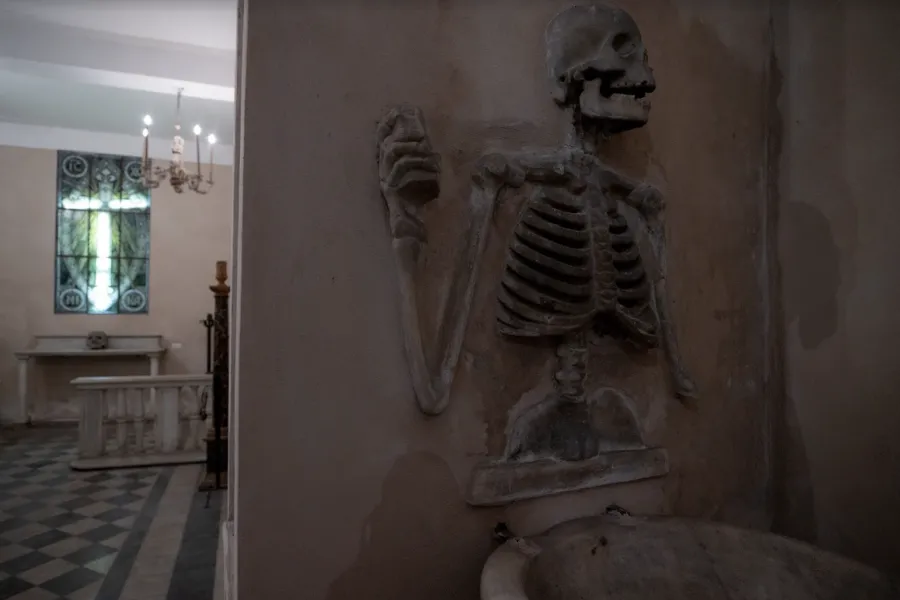

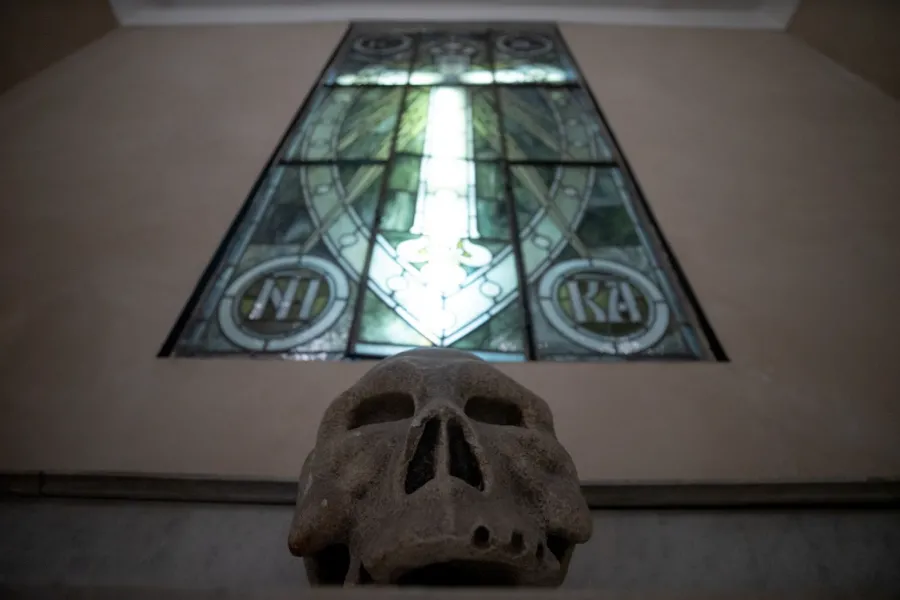

Santa Maria dell’Orazione e Morte (the Church of St. Mary of Prayer and Death) is the final resting place of the physical remains of more than 8,000 people buried by a charity dedicated to that cause.

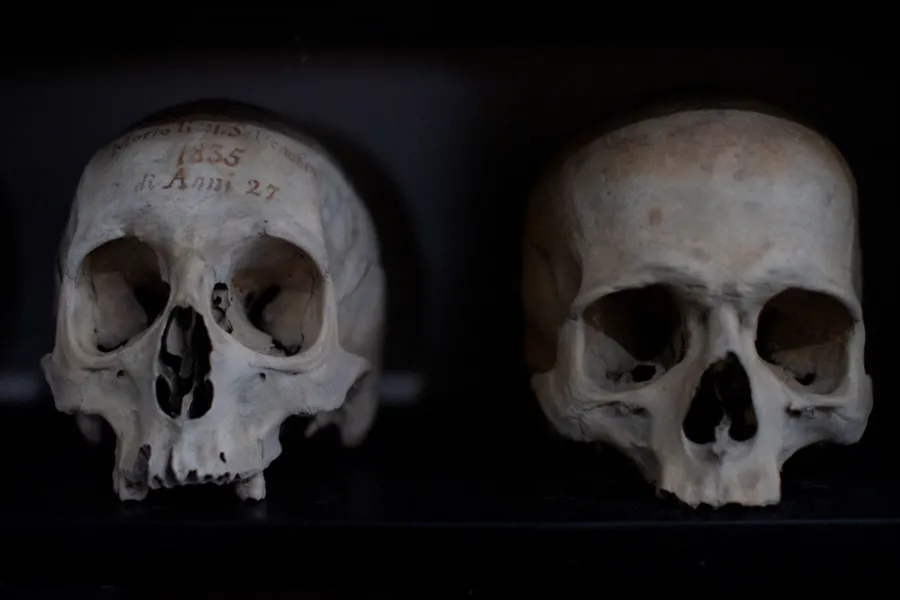

For much of its 483-year-old history, the Archconfraternity of St. Mary of Prayer and Death provided the poor — sometimes the unidentified bodies found in streets, fields, or even the Tiber River — with a funeral, burial, and prayers of suffrage.

The group still meets today to pray for those who have died and have no one to pray for them.

In the 1500s, when the confraternity was founded, the bodies of those who were too poor — or whose families were too poor — to pay for a burial, could be left to decay in circumstances unworthy of their human dignity. The confraternity was created to provide this spiritual work of mercy to those most in need.

For several decades, the Catholic group was hosted by various churches on Via Giulia, a road of just over 3,000 feet which runs on the east bank of the Tiber and is named for its patron, Pope Julius II.

Eventually, the confraternity built its own church. But in the first part of the 18th century it was torn down and the bigger Church of St. Mary of Prayer and Death was built in its place. This church and many of those used by the confraternity can still be visited today.

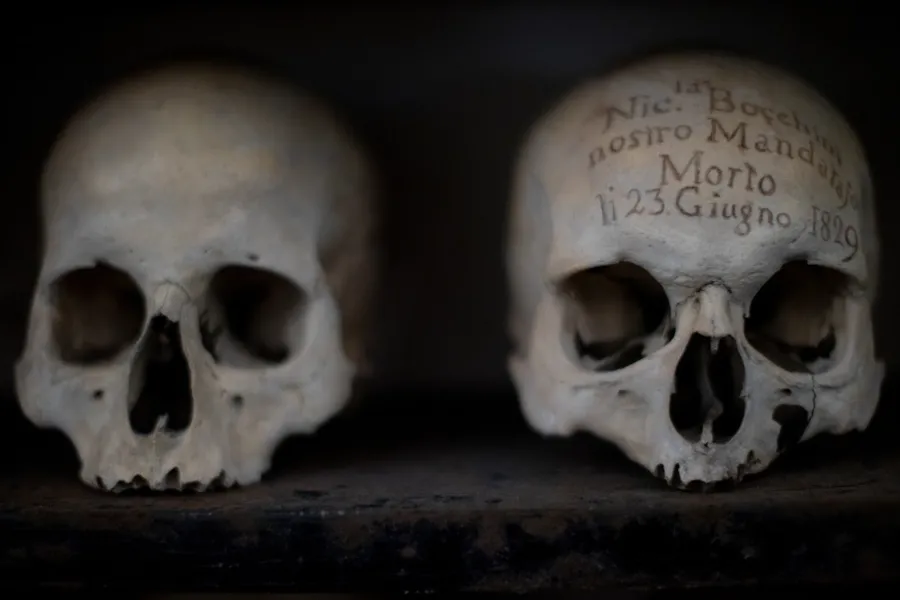

Records show that at least 8,600 bodies were buried in the church’s crypt and a cemetery on the banks of the Tiber from 1552 to 1896.

The outdoor cemetery was almost completely destroyed in 1886, however, when the walls of the Tiber River were constructed.

On its website, the confraternity recalls its “confrères who, with sacrifice, devotion, faith, courage, humility, abnegation, mercy, and fear of God, in the nearly 500 years of life of the confraternity, have observed this pious work of Christian charity.”

Today, on the wall of the crypt can still be read a prayer in Italian for the souls of those who have departed: “Eternal repose give to them, O Lord, and perpetual light shine upon them. May they rest in peace.”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply