Kyiv, Ukraine, Dec 9, 2022 / 08:55 am (CNA).

The train between Przemysl, Poland, and Kyiv, Ukraine, travels for 10 hours at night and is packed with people. Przemysl, a small Polish town 15 kilometers (about nine miles) from the Polish-Ukrainian border, has faced a refugee emergency during the last few months of the war in Ukraine.

It is estimated that 7 million people have crossed the Ukraine border with Poland since the beginning of the Russian aggression in February, and for many of them, Przemysl is the first port of call.

CNA recently traveled between Poland and Ukraine with a small delegation of Vatican reporters for a trip organized by the Polish and Ukrainian embassies to the Holy See. The trip offered a firsthand glimpse of the situation, a visit to the areas where there has been war, and a look at the future.

The train ride from Poland to the Ukrainian capital tells a double story. The first is that the people of Ukraine want to live again, even though the war is not over, and even though Russia underlines that the so-called special military operation will be over. Second, there is also a world that has arrived beyond the border of Poland because it didn’t know what else to do, not because it wanted to leave its territory of origin.

Przemysl

“I came to Przemysl because the mayor of Kyiv, Vitali Klitschko, invited us to leave the city because there would not be enough energy to heat us in winter. But I have no plans here,” a woman named Ludmila told CNA.

She is in her 60s, arrived alone, and is hosted in the first meeting center of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, which is based in Przemysl. There, the migrants arrive and are welcomed for 48 hours. Then they will decide whether to stay in Poland or go elsewhere. If the latter, a more comfortable destination will be found for them, and steps will also be taken to provide language classes so they can look for a job.

The structure, explained the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic bishop of Przemysl, Eugeniusz Popowicz, was obtained from a building that the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church received back from the state after the communists had confiscated it. Many bunk beds are arranged in the best and most dignified way possible, and a shared kitchen and a playroom for the little ones is now under construction.

In Przemysl, there is also a Caritas center, the “women and children” center, which brings together families of women with children.

There is Tatiana, who with her 7-year-old son and 13-year-old daughter fled the war while her husband was at the front. She has a tumor, worsened by her escape, but she has the hope “that war will lead to victory. The victory not only of Ukraine but of Caritas, of solidarity, of the love we have received.”

And then there is another woman, also named Ludmila, a grandmother who keeps her grandchildren while her daughters or daughters-in-law have had to stay in Ukraine. And there’s Tania, who is a bit like everyone’s grandmother.

In the Przemysl food bank, boxes of food for families are stored. Some also bring a Bible, in Ukrainian and English, with various necessities. The trucks also make four-day trips to the areas most affected by the war.

Kyiv

The theme of victory often comes up in the words of those who have fled or are in Ukraine because there is no solution or possibility of living peacefully.

“First of all, wars should not exist, as we human beings cannot ‘win’ one against the other. But I totally see the Ukrainian mind, as the word ‘survive’ means ‘to defend oneself’ in this war. This is what they mean by victory,” said Archbishop Visvaldas Kulbokas, apostolic nuncio to Ukraine.

“Every evening,” Kulbokas explained, “Russian programs speak of Ukraine’s victory, they underline that Ukraine is Russia’s property, they justify the current situation. From this, people can conclude that ending the war can only benefit them with a military victory.”

The nuncio welcomed the small delegation in the nunciature in a completely snow-covered Kyiv. There are still blackouts, but they are controlled, while the capital has come back to life after the Battle of Kyiv, which ended with a Russian withdrawal from that part of Ukraine in April.

By now, one is also accustomed to hearing rocket attacks in the distance. The traffic is heavy, and people go out. There is a more relaxed atmosphere here than there was during the early months of the war.

The nuncio is the only diplomat who remained in Kyiv — in addition to the Polish ambassador — during the siege. At the time, the staff of the nunciature had moved to sleep on the ground floor while tables blocked the entrances. But only a few anti-tank barricades remain near the government buildings from that time. For the rest, Kyiv has started to live again.

“Before the pandemic,” says the Latin bishop of Kyiv, Vitaliy Kryvytskyi, “they celebrated eight months in the cathedral every Sunday, attended by 1,500 people. After the pandemic, we had three Sunday Masses for a while, and now we have seven. We have canceled the English-language Mass because the students have left. In the same way, we have replaced the Russian-language Mass with the one in the Ukrainian language.”

The Catholic Co-Cathedral of St. Alexander had been confiscated by the Soviets, who from 1952 to 1990 used it as a planetarium. “The communists wanted people to see heaven, but not what was beyond the sky,” the bishop commented.

Decades of Soviet rule in Kyiv ended with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. In the context of the current Russian invasion, they remain a historical burden for Ukrainians, who hope to expunge this cumbersome past by cultivating memory and history. There is a museum, among other things, right in front of the center of the Orthodox Church linked to the Moscow Patriarchate, which displays Soviet weapons: helicopters lost in the war in Afghanistan, tanks, and remains of planes.

In this museum, the exhibition “Crucified Ukraine” was created, commemorating the days of the April 2022 siege of Kyiv by the Russians.

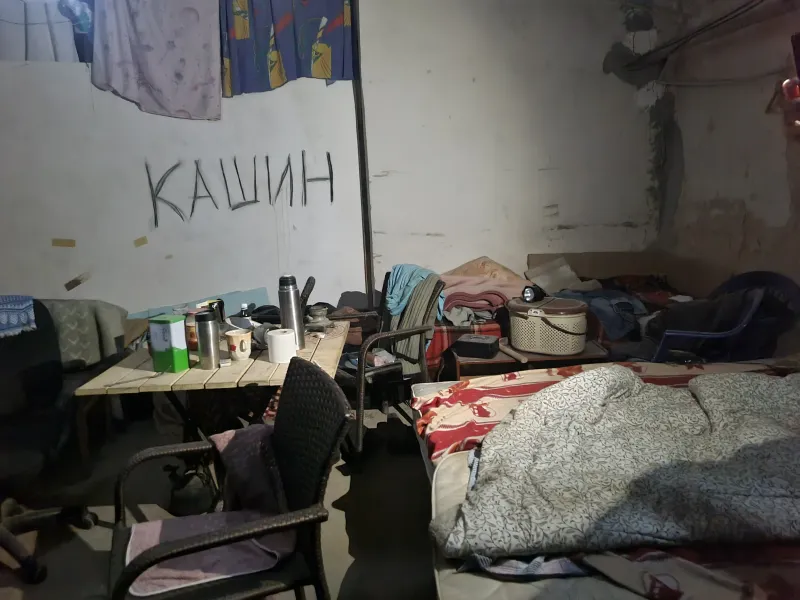

Indeed, one of the underground shelters is reproduced, painstakingly and precisely, with writing on the walls and labels on the food.

The curator of the exhibition explained that the Russian soldiers “only rarely allowed people to go out and go to supermarkets to get food or to cook outdoors. And in that case, at the checkpoint, people were forced to film videos in which they thanked the Russian military for their help.”

Incredible, however, is the desire to create memory when a historical memory has not yet been built. Ukraine wants to learn from past mistakes and does not want the past to come back. In this sense, it is significant that at the center of the exhibition is a painting of Jesus from a splinter from a church in the village of Peremoha, severely damaged by shelling in April.

Rzeszow

Everything seems standard now, but Ukrainians will have to deal with the most terrible general in Russian history — “General Winter.” In the winter, temperatures quickly drop well below zero, and heating is a tremendous challenge, given the electrical infrastructure is damaged.

For now, the emergency is no longer felt on the Polish-Ukrainian border in the Polish region of Podkarpackie, where the city of Rzeszow is located and which immediately faced the massive arrival of refugees from Ukraine. But there is the sense that an emergency will return.

Władysław Ortyl, president of the Podkarpackie Region, explained to CNA that “the first wave of refugees belongs to the past, but there is the possibility of a second wave, and this is caused by the fact that in Ukraine, many energy infrastructures have been destroyed, and therefore the risk of cold, the lack of water and services can lead to further refugees.”

Although the massive arrival of refugees from Ukraine has effectively doubled the population, the presence of Ukrainians is hardly felt in the city. The situation at the airport, on the other hand, is striking. It is a small civilian airport, used since January to land U.S. troops, who pass through the so-called “blue gate” and have installed patriot missiles that proudly protect the runways used by budget airlines.

It is officially a civilian airport, but the presence of troops — about 500, a soldier from Texas told CNA — makes it part military airport. Several areas cannot be accessed for security reasons.

“When the Americans arrived,” an airport official said, “they wanted their arrival, their troops, to be photographed to give Russia a signal of a strong NATO presence on the border. But now, strategic reasons prevail with the war, and so does information transparency.”

The airport thus represents the suspended situation of the entire region, divided between being a sort of enlarged front and place of refuge for refugees, between being Poland and being so close to the Ukrainian border, between being in an emergency and having overcome the crisis.

Then there is the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) center, where Polish is taught to those who arrive because, they said, “Ukrainians are very dignified people. They don’t want to live on mercy.”

There’s a young girl among them who explains how she would have liked to stay in Ukraine, but the bombs wouldn’t allow for it. Not far from the airport, there is the medevac medical center. The facility, almost new, can accommodate about 20 people for hospital-level emergency care. It is funded by the European Union.

Zaporizhzhia

Bishop Jan Sobilo of Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, comes from one of the areas most affected by the war. He says that when he arrives at the front (he tries to go once a week), he brings food and has to leave immediately because “the Russian troops know they are there and start shooting after five minutes to intimidate me.”

“The hospitals are full of wounded at the front,” Sobilo explained, “but all the people have great faith in victory and want to go back to the front so that the fight and the evil and all the cruelties that we are witnessing do not spread [to] all of Europe. They want to block all the evil that happens here.”

The bishop recounted having visited the Holy Father with the Latin bishop of Lviv, Mieczysław Mokrzycki, two weeks ago.

“While I was waiting for the meeting with the Holy Father,” he said, “I looked out the window and saw that they were decorating the Christmas tree in St. Peter’s Square. And then I [wondered] if we could have the Christmas tree in Zaporizhzhia. But, of course, it won’t be there in the square, but we will prepare it in the houses and wait for Jesus because Jesus, too, was born on a dark and cold night with only one candle.”

The bishop talked about the time he consoled a mother who lost her daughter, beheaded in a bombing, and when a grandfather whose granddaughter had been raped and killed turned to him for consolation.

“Those who die show us that love always wins, as Father [Maximilian] Kolbe said,” he noted, “and even in this situation today it will be like this because, after the war, the world will be spiritually reborn.”

Even the Latin bishop of Kyiv emphasized this need for psychological support in the face of a senseless war. A person might be physically consoled under normal circumstances, he said. “But if a person is a victim of rape, we know that we shouldn’t even touch them.”

Caritas assistance

The Caritas centers of Przemysl have helped 2,500 people, have sent 280 generators for electricity, and have various warehouses from which they distribute food in Ukraine. For a time, at least 200 trucks departed from there every day.

As of Nov. 26, the Foundation for the Pastoral Care of the Family had helped 1,454 refugees, paying for about 44,076 nights at a cost per person of about $22 a day — a considerable amount of money.

Amid the drama and sheer humanity of war — and the looming uncertainty of winter — the Church remains at the forefront.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply