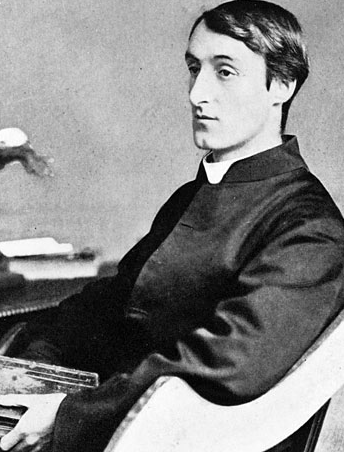

A new EWTN film about the Jesuit priest and poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-89) seeks to introduce the unique nineteenth-century Victorian-era writer to a wider audience. The film was made by Dr. Andrew Nash, who studied English literature at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was Head of English and a Housemaster at the Oratory School (founded by St. John Henry Newman). Nash, who is the first doctoral graduate of the Maryvale Institute, Birmingham, has lectured on Newman and his critical edition of Newman’s Lectures on the Present Position of Catholics in England was published by Gracewing in 2000.

Now retired from his former position as Headmaster of St. Edward’s School, Cheltenham, he spoke recently with CWR about the film Gerald Manley Hopkins: Priest-Poet, which will debut in the United Kingdom and Ireland on December 9th (12:00 pm London Time) and in the United States and Canada on December 18th (8:00 pm EST) on EWTN.

Edward Short for CWR: It is clear from the film that you are a great critical admirer of the work of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Can you tell our readers what it is about him and his work that first drew you to him? And when were you drawn to him?

Andrew Nash: When I was studying English literature at Cambridge University in the early 1970s, I found I couldn’t share the common enthusiasm for the Romantic poets like Wordsworth, and so I was put off nature poetry generally. I preferred the earlier “metaphysicals” like John Donne because their language and ideas were simultaneously strong and subtle, and reading them was exciting. Hopkins’ poetry had the same effect on me. His use of language was strikingly original; and as a young Catholic with an interest in theology, I was thrilled to discover that this extraordinary poet was profoundly Catholic. Even secular literary critics hailed him a ground-breaking writer, as great as the 20th-century modernists like T.S. Eliot. English literature since the Reformation has, for obvious reasons, nearly all been Protestant and latterly secular. In Hopkins, finally, there was a figure whom critics hailed as a great writer, even if they had no sympathy for his Catholicism.

My own life has not been given over to writing but to teaching school students. I found that Hopkins’ poems were particularly good for an “unseen” practical criticism exercise in which students are given a poem they know nothing about and have to tease out its meaning and how it achieves its effects. In parallel with teaching, and especially since I retired, I have become involved in editing the works of St. John Henry Newman, without whom Hopkins wouldn’t have become a Catholic.

CWR: You show in the film how Hopkins’ faith colored everything about his art. Can you elaborate on that?

Nash: Hopkins was one of the second generation of Oxford converts who were influenced by Newman, not through personal contact as in the early days of the Oxford Movement, but by the publication in 1864 of Newman’s Apologia pro Vita Sua. Like Newman, when Hopkins made his decision to become a Catholic he faced opposition from his family and exile from mainstream British culture. It also led directly to his discovery of his religious vocation as a Jesuit. Newman told him “they will make a saint of you.”

Beauty, both in nature and in people, had a strong emotional effect on Hopkins. Without his conversion and his subsequently becoming a Jesuit, he would almost certainly have drifted into mere aestheticism and a morally decadent lifestyle. The iron discipline of the Jesuit life was what he knew he needed, and it was out of that crucible that he was formed as a poet. Secular culture today always presents Catholicism as repressive—Hopkins’ life shows exactly the opposite: it was the great creative force of his poetry.

CWR: You also show how nature moved Hopkins, though his relationship with nature was not the sort that we associate with Wordsworth or the other 19th-century Romantic poets. How does Hopkins’ relationship with nature differ from theirs?

Nash: In his autobiographical poem “The Prelude,” Wordsworth records the terrifying experience he had one night when he rowed out into the great Ullswater lake and suddenly became aware of the huge mass of a mountain which “Towered up between me and the stars, and still,/For so it seemed, with purpose of its own/And measured motion like a living thing,/Strode after me.” This is more like an experience of a malevolent pagan deity than of the Christian creator God. In the poem he goes on to address the pantheistic “Wisdom and Spirit of the universe!/Thou Soul that art the eternity of thought.”

Contrast this with Hopkins’ “The world is charged with the grandeur of God./It will flame out, like shining from shook foil,” which ends with the tender image of how “the Holy Ghost over the bent/ World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.” Hopkins sees nature as shot through with God’s presence. More than this he is Christocentric: he knew that all creation is made through and for Christ, and so he can look at a flower and say “I know the beauty of Our Lord by it.”

CWR: Hopkins tends to have two registers: one celebratory and the other rather less than celebratory. What does this tell us about his deep faith?

Nash: Hopkins’ characteristic tone is indeed celebratory about nature, even ecstatic at times. He is uninhibited about being utterly joyous—as one of his titles, “Hurrahing in harvest” shows—and his use of sudden exclamations, like “Ah!” But there are also the “terrible sonnets,” as they have been called, which Hopkins wrote during his unhappy final years in Dublin. I hesitate to call these poems enjoyable—they are terrifying in their expression of his struggle with depression. What psychological and spiritual agonies lie behind lines like “O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall/Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap/May who ne’er hung there.”

One could say that Hopkins truly went through a dark night of the soul. As I show in the film, however, because of his faith he never despaired. None of us know how strong our faith is until it is tested. Hopkins’ faith certainly was, and he expresses this with searing honesty in these poems. There is one in which he reflects with great sadness how he hasn’t been able to achieve anything (his poems were never published in his lifetime), calling himself “time’s eunuch.” And the poem ends with the desperate plea, “O Lord of life, send my roots rain.”

CWR: With the help of Father Richard Conrad, OP, you share with your viewers the influence that the medieval Franciscan philosopher and theologian Duns Scotus had on Hopkins, especially on his delight in the inimitability of things. Can you tell us how this is reflected in his poems?

Nash: Scotus taught that individual things are not just examples of general ideas; he saw individual things a having a “this-ness” (in Latin, haecceitas) which meant, for instance, that two chunks of the same stone, though having identical physical characteristics, each have their own individuality. When Hopkins read about this during his philosophical training, it chimed with his own view of nature. He observed things very closely, making detailed drawings of individual plants and trees. He saw each thing as having its own unique “inscape”—by which I suppose he meant a thing’s unique internal landscape. It’s not that he got the idea from Scotus and then applied it to nature; rather it was a case of the philosopher’s concept and Hopkins’ own insight coinciding. Scotus’ philosophy assured Hopkins that his own view of nature was true and valid.

But there was also a theological insight of Scotus’ which gave even greater depth to Hopkins’ Christocentric view of nature and of human beings. Scotus (who is now a Doctor of the Church and so we can be sure his theology is orthodox) taught that God did not become incarnate in Jesus Christ just as a sort of divine rescue mission because of Man’s sin. Rather, as the early Greek Fathers of the Church had taught (and which is implicit in St. Paul), God always intended, before the Fall, to become incarnate, to share human nature so that humans could come to share God’s nature. Human beings are modeled on Christ and they are for Christ. And so we can see Christ in human beings. As Hopkins put it in one poem: “Christ plays in ten thousand places,/Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his/To the Father through the features of men’s faces.”

CWR: One striking thing about Hopkins is his utter originality. Although he was influenced by other poets—Walt Whitman, Crashaw, and Tennyson come to mind—he is utterly unlike any other poet. He is also not an easy poet to understand. And yet he has always enjoyed a truly popular readership. How would you account for this—his ability to gain and move readers despite the demands his poetry makes on them?

Nash: Hopkins can indeed be a “difficult” poet—sometimes so obscure that, without the aid of a good editor’s notes, it can be hard to make out what he’s saying. This is because Hopkins puts words together in unconventional ways—he crashes words against each other to create new poetical effects. However, you can “get” these effects by just reading aloud his words, letting the sound of them impact on you, rather like listening to music. For example, his poem about a falcon in flight, “The Windhover,” begins: “I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-/dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding/Of the rolling level underneath him steady air.” Feel those internal rhymes and the alliteration and assonance. You can later think about what exactly Hopkins means by calling this beautiful bird “daylight’s dauphin,” but before that you can get a feeling of its superb movement and Hopkins’ sense of wonder and exhilaration in it.

The same is true of so much of his verse: it’s more than lyrical—it’s musical. His lines roll round one’s tongue and then round one’s mind. Try reading aloud these lines about nightfall: “Earnest, earthless, equal, attuneable, vaulty, voluminous…stupendous/Evening strains to be time’s vast, womb-of-all, home-of-all, hearse-of-all night.” All good poetry sticks in one’s head, of course, but once you’ve got the sound of Hopkins, you’ll find that you develop an “ear” for him. It’s like what happens when you first experience a Shakespeare play in the theater: at first you can’t follow in detail what is being said, but gradually you get tuned to his verse and you are drawn into the dramatic experience.

One other thing about Hopkins’ verse I should add is that he doesn’t write in regular metre, nor does he write free verse. He adopted what he called “sprung rhythm,” which had been used by medieval poets like Langland and relies on how stresses fall irregularly in a line. He wrote a lot of highly technical stuff about this and gave some of his poems detailed markings to show how it worked. But you don’t need to know all that to enjoy the poetry—just read it as it comes naturally and the sprung rhythm will work.

CWR: Art and faith go hand in hand, and yet we live in a culture in which this is rarely the case. Hopkins reminds us that Western Civilization—if we can still speak of the dear old thing—is grounded in devotion to Mary, in delight in Mary’s beauty. Hopkins grew up amidst the aesthetic movement of the French decadents and Walter Pater. And yet his insistence on beauty is always on the beauty that animates Marian devotion. Can you tell our readers what you make of Hopkins’ preoccupation with beauty? How is this celebrated in the poems?

Nash: His preoccupation with beauty stems from his awareness that celebrating it is a both a joy and a problem. He knows that all beauty comes from God, but he also knows that human beauty can be a source of temptation. He asks in one poem: “To what serves mortal beauty—dangerous; does set danc-/Ing blood—the O-seal-that-so feature, flung prouder form?” Indulging in it, like hedonists, as the aesthetes did, leaves only bitterness and despair when it is gone. Also, how can something be so good and yet so transitory? These are paradoxes which the non-Christian thought of his day did not resolve (and our post-Christian culture has given up even trying to resolve). But Hopkins’ faith and his religious vocation found him a way.

You can see him debating the issue in his poem “The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo,” which begins by asking “How to keep—is there any any, is there none such, nowhere known some, bow or brooch or braid or brace, lace, latch or catch or key to keep/Back beauty, keep it, beauty, beauty, beauty, … from vanishing away?” In the second part he answers: “Give beauty back, beauty, beauty, beauty, back to God beauty’s self and beauty’s giver./See; not a hair is, not an eyelash, not the least lash lost; every hair/Is, hair of the head, numbered.” By his Christian faith Hopkins knows that when we freely give back to God the beauty we have, it will be kept by God “with fonder a care.” It is striking that Hopkins, an austere 19th-century Jesuit, living a life of ascetic self-denial, could at once celebrate—revel in—earthly beauty but also understand how it can be returned to its origin, God.

As regards the Marian dimension, I should mention something else that Hopkins loved about Scotus’ writing, though we didn’t have space to include this in the film. Scotus championed the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception at a time when it hadn’t been defined as Church teaching and was disputed by many theologians. Scotus turned out to be right when the doctrine was defined by Pope Pius IX in 1854. Hopkins rejoiced that Scotus had “fired France for Mary without spot.” His enthusiasm for Mary’s sinlessness is part of his view of human nature—Mary is what human beings were meant to be like, before the disaster of sin. She is the New Eve (the patristic idea that Newman said underlay the Church’s whole Marian doctrine). Hopkins wrote some specifically Marian poems, including the remarkable “The Blessed Virgin Compared to the Air we Breathe,” but in a way you could regard all his poems as Marian because he celebrates the sinlessness of all Nature as God made it, and Mary is God’s most perfect creature.

CWR: Admirers of poets always have their favorite poems. What are some of yours from Hopkins and why?

Nash: I suppose they must be the ones I put into the film! But it was very hard to select the few we had space for. I begin the film with some extracts from “The Wreck of the Deutschland” because writing it marked the beginning of Hopkins’ mature poetry. But it’s not my favorite; the poem itself is long and the first section is extremely difficult, so I wouldn’t recommend it as the place to start reading Hopkins. I prefer his sonnets, such as his famous “The Windhover” and “God’s Grandeur.” There are times when Hopkins writes very simply, and I am fond of his “Spring and Fall,” which begins with the direct, “Margaret, are you grieving/Over Goldengrove unleaving?” particularly as a musician friend (the British concert pianist Nicholas Walker) set it to a haunting melody as part of a wedding present for my wife and me.

If I had to choose just one poem from Hopkins’ rich output, it would be the one which, despite being written during his final unhappy years, I think expresses his faith most thrillingly. It has a very challenging title: “That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the comfort of the Resurrection.” Heraclitus was an ancient Greek philosopher who taught that the universe is in a constant state of flux, so that nothing is permanent. I chose this as the final poem in the film, and I hope viewers will share my love of this triumphant poem of what the Resurrection means for Hopkins, and for us.

CWR:You and your film-making friends set out to make the excellent film you made to reach a certain audience. Which audience? And what should you like the film to accomplish?

Nash: Hopkins is now very well known in the academic world—it’s remarkable how he fascinates even secular literary critics. But I don’t think he has much name recognition among ordinary Catholics, and these are the audience I want to introduce him to. I think it’s important for Catholics today to appreciate that we have a great literary heritage, that there are writers who are as good as—in Hopkins’ case much better than—famous non-Catholic writers, like Wordsworth, that we’ve all heard of.

Newman speculated (in The Idea of a University) that there would never be an English Catholic literature because the literary canon had been formed in such a strongly Protestant culture. But I think that in this case he has turned out to be too pessimistic. Alongside non-Catholic (and now post-Christian) mainstream culture, there has gradually emerged a distinctive modern Catholic literary stream. And in Hopkins we have a writer of major stature. We should rejoice in him. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with simple, popular devotional writing—we mustn’t be spiritual snobs. But Hopkins gave us poetry of enormous literary power and profound theological insight which can nourish us today.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Looking forward to this film.

We read that Hopkins (1844-89) “observed things very closely, making detailed drawings of individual plants and trees. He saw each thing as having its own unique ‘inscape’—by which I suppose he meant a thing’s unique internal landscape.”

No less intent on singular realities, but also much more on external systems like food chains, the scientist Charles Darwin (1809-82) still based his entire theory of classification on a keen eye for the particular, e.g., a particular kind of flower…

Late in life, Darwin (Hopkins’ contemporary) cherished most his relatively obscure paper in the Journal of the Linnean Society examining something so specific as a particular kind of flower: “I do not think anything in my scientific life has given me so much satisfaction as making out the meaning of the structure of those plants” (“On the Two Forms, or Dimorphic Condition of Primula”: the existence of two forms of cowslip with different lengths of pistils and stamens).

Not Tennyson’s “flower in a crannied wall,” nor Wordsworth’s “simplest flower that blows,” nor Hopkins’ own “individual drawings of plants and trees”–But, what a graced moment there might be when together the scientist and the poet someday share a brew around, say, a fresh-cut lily in a Christian pub…

Perhaps even to notice together the uniquely singular event of the Incarnation at the center of human history, which does not suffer replicated verification through any mere, controlled, scientific lab experiment, but only through the myriad souls of individual saints fed by the sacramental life of the Church.

When one’s faith is tested, one makes a choice. When faith is not tested, one takes it for granted. Long live the memory of Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Wonderful to see Hopkins being appreciated! Perhaps the most original voice in all of poesy.

His vivid, unrestrained, full-throated love for our Creator renews even the English language.

Sure does.

I applaud Dr Nash’s vision and initiative in making this film, and look forward keenly to seeing it.

As the interview reveals, Hopkins was no green pantheist: while recognising and celebrating creation in all its “pied beauty” and “skeined, stained, veined variety”, Hopkins never loses sight of the Giver behind the gift. For him, nature manifests the majesty and generosity of its Maker, the original and originating Artist. Hopkins helps us appreciate and celebrate God’s beneficent providence, providing a sane corrective perspective in poems such as “God’s Grandeur” to the despair of doomsday environmental alarmists. Hopkins’s appreciation of nature is

based on and encourages a theological vision of gratitude, hope and stewardship.

Am a fan of Hopkins since being introduced to him by a high school English teacher in the 1950s. Looking forward to seeing this film.

One correction: Duns Scotus has not been declared a Doctor of the Church.

Many thanks to Dan Baedeker for pointing out my mistake in terming Scotus a Doctor of the Church. My apologies for this error. However, Scotus was widely known as the ‘Doctor Subtilis’ for the subtle nature of his thought. I hope that one day he will be both canonised – he was beatified by Pope St John Paul II in 1993 – and formally declared a Doctor.