“During the past forty years, the Church in China has suffered severe persecution. . . . Please pray for the suffering Church in China!” – Ignatius Cardinal Gong Pinmei (June 30, 1991)

The Vatican has signed a “provisional” agreement with China’s Communist government, and for the first time in several decades all of China’s Catholic bishops are in full communion with the pope. The agreement was not unexpected; negotiations have been at an advanced stage since February and March. In addition to the agreement regarding the future election and consecration of bishops, Pope Francis has removed the excommunications of seven bishops who has been ordained without the Vatican’s consent.

This has precipitated confusion and frustration within online discussions by Chinese Catholics, especially since one of the bishops who the Holy Father has accepted into full communion, Peter Lei Shiyin, was excommunicated in 2016 after his ordination because he was consecrated without papal mandate, and also because it was widely rumored in China that he was in a relationship with a woman and had a child with her at the time he became a bishop. The former bishop of Beijing, Michael Fu Tieshan, was also known to have “been married” while fulfilling his pastoral leadership in China. Whether these rumors are factual remain in question, but they had been sufficient to prevent the Holy See from finalizing an agreement with China’s state officials as it was felt prudent to not only await a time when China’s Church was less controlled by the Communist Party but also a time when state-controlled bishops such as Peter Lei and Michael Fu were less implicated in China’s ecclesial rumor mills.

More to the point, many of China’s Catholics, not to mention many Catholics all over the world, are mystified as representatives of the Catholic Church—which has made its views on atheistic Communism forcefully clear over past decades—have just sat at the table with a Communist Party official and signed an agreement of collaboration. For his part, China’s current leader, Xi Jinping, has made his commitment to Communism and the legacy of Chairman Mao known in several speeches. He once praised the iconic founder of Communist China, saying: “Comrade Mao, whether he was crossing ‘a sea of surging waves’ or scaling ‘a mountain pass impregnable as iron,’ always held unwaveringly to his course, setting a shining example for the Chinese Communist Party.” China’s government has grown more adamant about its pledge to Communist rule over the past several years, which is why so many Catholics in China are perplexed by the Vatican’s willingness to negotiate with Beijing’s Party officials at this particular moment. Papal statements about Communism in recent decades have not been forgotten by Chinese Catholics. For example, in the 1961 encyclical Mater et Magistra, Pope St. John XXIII stated, “Pope Pius XI further emphasized the fundamental opposition between Communism and Christianity, and made it clear that no Catholic could subscribe even to moderate Socialism” (n. 34). Pope St. John Paul II was also, of course, a vocal opponent of atheistic Communism, and is often attributed to the fall of the Party in Poland and the USSR, though he claimed little credit, saying, “I didn’t cause this to happen. The tree was already rotten. I just gave it a good shake and the rotten apples fell.”

Pope Francis has adopted a different tone and approach than that his predecessors. In a November 2016 interview with the atheist journalist Eugenio Scalfari, Pope Francis responded to a question about Communism in these words:

It has been said many times and my response has always been that, if anything, it is the Communists who think like Christians. Christ spoke of a society where the poor, the weak and the marginalized have the right to decide. Not demagogues, not Barabbas, but the people, the poor, whether they have faith in a transcendent God or not. It is they who must help to achieve equality and freedom.

If this response is indeed accurately recounted (Scalfari is not known for his commitment to accuracy), then Chinese Catholics have sound reason to fear Vatican relaxation of the Church’s long critiques of Marxist thought. Some are now asking if the Church still seeks to shake down the “rotten apples” of Communism—or to join them in the same barrel.

Why this agreement has caused confusion

The Vatican News Communiqué, released on Saturday, September 22nd, reveals very little of the provisional agreement’s contents. It merely describes the agreement as concerning “the nomination of Bishops, a question of great importance for the life of the Church, and creates the conditions for greater collaboration at the bilateral level.” The final sentence of the short document asserts, “The shared hope is that this agreement may favor a fruitful and forward-looking process of institutional dialogue and may contribute positively to the life of the Catholic Church in China, to the common good of the Chinese people and to peace in the world.” China’s Catholics, the vast majority of whom have resisted Communism in some fashion, discern mixed messages coming from the historical Church. “Collaboration at the bilateral level” is unambiguous; it implies the fraternization, or even an alliance, between two parties. Cardinal Gong Pinmei was imprisoned for thirty years in the notorious Ward Road Prison in Shanghai because he refused to collaborate with China’s Communist Party, and many other Chinese priests, probably thousands, likewise suffered for refusing to cooperate with China’s officials. Many of the Chinese priests who endured decades in Chinese prison did so after reading Pope Pius XI’s encyclical, Divini Redemptoris, wherein the Holy Father condemns Communism as the work of the Evil One. Of Communism’s rise in the 1930s, Pius XI wrote:

The struggle between good and evil remained in the world as a sad legacy of the original fall. Nor has the ancient tempter ever ceased to deceive mankind with false promises. . . . This all too imminent danger, Venerable Brethren, as you have already surmised, is Bolshevistic and atheistic Communism, which aims at upsetting the social order and at undermining the very foundations of Christian civilization (Divini Redemptoris, March 19, 1937, nos. 2-3).

How, many ask, can one rationally reconcile the Church that Cardinal Gong suffered for and the Church today that advertises its “collaboration” with a Communist government?

In a short reaction to the agreement, Joseph Cardinal Zen regrets the Vatican’s lack of transparency on such an important matter as what appears to be a cooperation with forces that have been consistently denounced by previous popes. After the agreement was signed, Zen asked:

What is the message the Holy See intends to send to the faithful in China with this statement? Have faith in us, accept what we have decided? And what will the government say to Catholics in China? Obey us, the Holy See already agrees with us? Are we to accept and obey without knowing what must be accepted, to what one must obey? An obedience tamquam cadaver [obedience of a dead man] to quote Saint Ignatius?

In other words, Cardinal Zen acknowledges the impossible position China’s Catholics are now in because of this agreement. In a recent Reuters interview, Zen exclaimed: “They’re giving the flock into the mouths of the wolves. It’s an incredible betrayal.” Priests within China, too, have expressed their fear over what this agreement might entail. One anonymous priest lamented the fact that no Chinese prelates who truly understand the Catholic Church in China, leaders such as Archbishop Savio Tai Fai Hon, John Cardinal Tong Hon, or Joseph Cardinal Zen (all appointed to advise Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI), were invited to participate in the negotiations with China’s Communist Party.

Another unidentified Chinese priest, who acknowledges the success of other Vatican negotiations with Communist regimes (such as in Vietnam), insists that this agreement with China is fundamentally different. He writes:

In fact, we have all along hoped for an agreement and the establishment of diplomatic relations. However, this agreement and diplomatic relations should not be achieved at the cost of abandoning the Church’s longstanding disciplinary rules or her bottom line. Furthermore, we should consider the creditworthiness of the negotiating parties. When did the Communist Party become credible since it was born out of lies? Except for its policy to impose violence on people of different ideologies – which is quite convincing – are there any other believable policies whose only aim is to maintain the stability of the government?

Accompanying this priest’s remarks is a photograph of two Chinese policemen holding a banner that reads, “Firmly reject religion, do not believe in religion (决拒绝宗教,不信仰宗教).” This kind of official pressure against religion, the priest insists, is precisely why now is not the time for the Vatican to sign an agreement with China’s government. In reality, most Chinese Catholics probably welcome some form of agreement between Rome and Beijing, just as long as it does not compromise the faith and it does not actually endanger China’s Christians more than they have been in recent years. “Not yet,” is what one hears many Chinese Catholics plead. Of the twelve million Catholic faithful in China, five million are listed in the register of the “official Church”; the remaining seven million attend Masses in the “underground Church,” and it is these Catholics who display the most anxiety about an agreement at this moment.

Chaos benefits Communist goals

I have spent many years of my life living in China, and I love China; it is like a second home to me. I am also a professor of Chinese history, and I can attest that the history of Christianity there has always been plagued with tension and conflict, though Chinese cultural suspicions of Western religion are not always unwarranted. Looking at the long history of Catholicism in China, the present situation there for Christians is particularly fraught with disagreement and danger.

“When everything under heaven is in utter chaos,” exclaimed Chairman Mao, ” the situation is excellent.” Mao believed that Marxism is the best approach to creating a classless society, and he also believed that violence and chaos are the best ways to assure that a classless society is maintained. It is astonishing that the Holy See is presently making diplomatic overtures toward a government that not only uses tactics of division and confusion to control its people, but also unambiguously asserts its aim to eliminate religion. In 1982, an influential Communist journal, Hongqi (Red Flag), outlined the Party’s view of religion: “Religion is an inevitable phenomenon at a certain stage of human history. This phenomenon must undergo the stages of emergence, development, and disappearance” (Hongqi, June 16, 1982). While religious freedom is ostensibly assured under the Chinese Constitution (Article 36), the state’s explicit policy is to guarantee that religious belief dissolves under the persistent efforts of political policy and propaganda. Mao supported chaos because chaos engenders a people occupied with revolution and anti-religious ideology.

I recently returned from a month in China where I attended Mass and spoke with Chinese Catholics, who expressed their confusion then over the latest Sino-Vatican negotiations. A tide of media sources had mentioned a puzzling statement by Bishop Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo, the chancellor of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, who said in an interview with Vatican Insider that “at this moment, those who best realize the social doctrine of the Church are the Chinese.” That is a very different view of China’s government than was expressed by an exiled Archbishop of Nanjing, Yu Bin, during the Second Vatican Council. Archbishop Yu called the Council fathers to recognize the fact that, “There is never absent, wherever Communism is in political control, a bloody, or at least legal, persecution or stifling liberty” (Archbishop Paul Yu Bin, Second Vatican Council, “Mentioning Atheistic Communism by Name,” October 23, 1964). Two more dissimilar views of China’s government and its ideological goals can hardly be imagined.

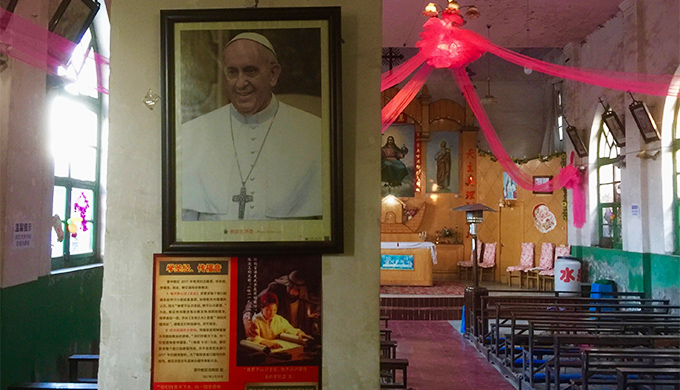

China’s official enforcement of birth control and forced abortions can hardly be described as a state that “best realizes the social doctrine of the Church.” Nor can it be said that a state that is currently bulldozing churches and regularly arrests clergy who refuse to abide by state oppression is an exemplary agent of Catholic social doctrine. News reports over the past several months have proven wrong those who would suggest that the Chinese Communist Party has changed its view toward religion in general and Catholicism in particular. An article in the South China Morning Post, for example, revealed that thousands of poor Christians “in rural southeast China have swapped their posters of Jesus for portraits of President Xi Jinping as part of a local poverty-relief program that seeks to ‘transform believers in religion into believers in the Party’” (South China Morning Post, November 14, 2017). The article included several photographs of Christians replacing their Christian images with large photos of Xi Jinping.

While some in China’s sanctioned community view this agreement as potentially helpful, the majority of China’s Catholics express confusion, and even a sense of betrayal, as Rome appears to be aligning itself with a Communist government that has proved itself inconsistent in its treatment of Christians. From the Vatican’s point of view, normalizing relations with China’s government could mean the pope would finally be empowered to select (at least ostensibly) who can be consecrated a bishop in China. But even if Sino-Vatican relations are normalized, many Chinese Catholics find it difficult to imagine that Beijing’s anti-Christian policies will disappear.

Even so, there is another view of what is happening between the Vatican and Beijing. While in China I have met many bishops, priests, sisters, and lay faithful, and commonly expressed this perspective: “The best thing that could happen to Catholics in China would be a visit from the pope – a pope has never been to China!” While for some the recent political choreography being arranged by Vatican officials appears contradictory and chaotic, for others these moves seem to follow a carefully orchestrated plan to finally achieve an accord between the Holy See and Beijing – and perhaps the first papal visit in China’s history. Perhaps China’s government thinks that it would gain much positive attention by normalizing relations with the Holy See, especially as it begins to prepare for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games. China’s rising international profile means that something like a papal visit, if that is indeed on the negotiating table, could potentially add much to China’s diplomatic prestige.

It is impossible to predict how this Sino-Vatican rapprochement shall affect China’s Catholics; perhaps it could be a balm of hope after decades of suffering. Still, any savvy historian of China’s Catholic past understands that no matter how friendly and careful the pope’s diplomacy is toward China’s Communist government, Party officials have not lessened their disdain toward religion and their distrust toward the Holy See. In 2014, the government allowed the pope to fly over Chinese airspace, which was viewed by many as a thawing of Sino-Vatican enmity. But, when Pope Francis invited President Xi Jinping to visit him in Rome, Xi quickly declined. And when the pope again asked Xi to meet with him at the 2015 New York General Assembly, Xi again refused.

This is not the first time that we have seen mixed messages coming from China’s Communist leaders; mixed messages have always been a strategic part of Beijing’s political apparatus. The problem I see with this Sino-Vatican agreement is that it is now the Vatican that appears to be sending mixed messages.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Just yesterday, I received a message from a priest I know in China. Chinese Catholics are more than just “dismayed” by the actions of Pope Francis. They feel betrayed, and they are angry and fearful. This priest told me he and others are praying daily for a new pope.