MPAA Rating: R

USCCB Rating: NR

Reel Rating:![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (4 reels out of 5)

(4 reels out of 5)

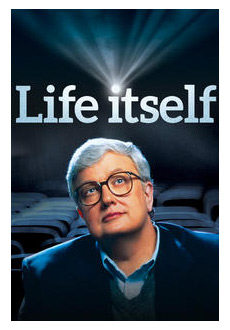

Roger Ebert was the most well-known film critic of all time, a man whose career “spanned half the history of motion pictures.” Yet while enduring a debilitating illness, he also became a wonderful reviewer of life itself, culminating in an autobiography from which this work derives its title. The film delivers a sound summary of Ebert’s journey from being the blue-collar son of an electrician to an alcoholic journalist to a master of the English language, but it also excels at demonstrating his passion for film and the effect he had on the industry. It’s a very compelling documentary that is oddly absent of his thoughts on religion, especially his Catholic upbringing, yet nonetheless is essential viewing for any lover of movies.

From the opening scene, director Steve James makes his presence and purpose known to the audience. Roger Ebert even asks James to point the camera to a mirror so viewers know who is telling the story. This is fitting as James is one of countless filmmakers who owes Ebert much of their success; his documentary Hoop Dreams was named by Ebert as the best film of the 1990s.

James begins in December of 2013 with Ebert stationed at a local hospital, suffering greatly from a fractured hip. But that is not the most dramatic medical element. In 2006, Ebert suffered a ruptured artery after a difficult operation to remove a tumor in his jaw, leaving him unable to speak, eat, or drink. However, this does not daunt his spirits as he continues to review movies and blog about all elements of life. His humor and courage calls to mind the final days of St. John Paul the Great, who continued his ministry publicly despite a disease the progressively robbed him of all motor function. While it is difficult to watch Ebert wince in wordless pain as fluid is drained from his trachea, the scene encourages respect and dignity for the disabled, aged, and dying.

Interspliced with his hospital visits and rehab sessions, James allows Ebert to narrate his life story. The only child of populist Michigan parents, Ebert was a natural writer who began publishing his own newspaper while in his teens. Rising through the journalist ranks to become the Chicago Sun-Times’ film critic, he won a Pulitzer Prize in 1975 when just thirty-three years old. After a brief and bizarre stint as a screenwriter for a series of sexploitation films—which his television producer tries in vain to explain—he landed international fame as the rounder and earthier half of Siskel & Ebert with his frienemy from the Chicago Inquirer, Gene Siskel. Ebert continued to widen his cinematic insight with writing, teaching classes, attending festivals, and hobknobbing with the rich and famous at red carpet events. As the documentary progresses, Ebert grows weaker and weaker until a heartbreaking end that is sadly incongruent with the rest of his life.

It’s very rare to see a man who finds his passion early, is extremely skilled in that area, and comes at the right time and circumstance to allow that passion to thrive unbounded. Emerson’s famous adage comes to mind: “pick a job you love and you’ll never have to work a day in your life.” Yet Ebert not only loved film, he loved the people involved and helped others in pursuing their dreams and projects. James interviews several filmmakers who got their start by simply asking Ebert to view their movies. Even the great Martin Scorsese, usually known for his gab and pleasant wit, briefly begins to break down as he recalls how Ebert brought him out of a deep depression in the early 1980s, convincing him to continue make movies (including Raging Bull).

Ebert’s television show also brought his intellectual observations to the common moviegoer, igniting scores of amateur internet blogs like Ain’t It Cool News and Awards Daily. Ebert fully embraced this movement, posting all of his reviews online for free. Great artists aren’t afraid of competition because they know it will only advance the medium; artistic talent and love for the creative life are meant to be shared.

Despite his success, Ebert had a dark side and was only too willing to admit it. Nights during his twenties and thirties were frequently spent in bars with seedy women. Rare was the morning that did not start with a hangover. A friend recalls Ebert picking up a prostitute and then entrusting her with someone else to get her home. In 1979, he quit drinking, joined Alcoholics Anonymous, and started cultivating important friendships. In 1992, he married trial attorney Chaz Hammelsmith and became stepfather to a large family. His final years saw an outpouring of affection and a deep need to help humanity. Ebert blogged not only about movies but also important issues of the day such as religion, politics, philosophy, and his decreasing health. A film critic should be interested in all aspects of life as the art form deals with every subject under the sun. It is this exposure to a wide range of ideas that Ebert saw as film’s greatest strength. He called it “an empathy generator,” where for two hours people experience what it’s like to be in someone else’s shoes.

The greatest flaw with Life Itself is that it completely ignores Ebert’s intense interest in spiritual matters, especially regarding his Catholic upbringing. He would frequently mention his days in Catholic grade school and being an altar boy, even defending priests when the sexual abuse scandal broke in 2002. For someone who had an oddly intense attraction to sexually explicit films, Ebert had a very strong moral compass. He often gave poor reviews to films he felt violated these norms, calling Blue Velvet “disturbing” and Wolf Creek a “sadistic celebration.” He also blogged frequently about religious matters, telling his audience:

I consider myself Catholic, lock, stock and barrel, with this technical loophole: I cannot believe in God. I refuse to call myself an atheist however, because that indicates too great a certainty about the unknowable.

Most of this is missing from the film, however, except for one very funny (albeit mean) comment about Siskel’s Protestantism. For an excellent survey of Ebert’s faith, I recommend Steven Graydanus’ moving obituary.

If a film is measured by the empathy it shows, Life Itself is wonderful. James effectively captures one man’s life, honestly portraying the good, the bad, and some of the transcendent. Ebert’s life is living proof that if one embraces their talent and pursues their passion, amazing things can happen. Many who knew Ebert took this to heart and now seek to carry on his legacy. I am one of them.

While a struggling film student in 2006, I e-mailed Ebert asking about his Catholic faith and if he could recommend any good Catholic movies. To my great surprise, he responded about a month later. “Dear Nick,” he wrote. “I’m not a very good Catholic anymore, but I do recommend Dairy of a Country Priest. Sincerely, Roger.”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.