Few coal miners wanted anything to do with the stranger in the black cassock who arrived in town in 1933. It was the Great Depression in West Virginia—food was scarce and shifts were irregular. So nerves were raw in the pits when miners spoke about unionizing against deadly conditions. The last thing anyone wanted, as they emerged at sundown, was a young Catholic priest pressing his unfamiliar ways upon them.

Father Charles Carroll understood he was an outsider. In Anmoore, Wendel, Philippi, Brownton, Rosemont, Galloway, and Bridgeport, most families were rock-ribbed Appalachian Protestants—Bible-only believers who trusted Scripture, not Rome. The Catholic population was thin in this remote stretch of north-central West Virginia, where cold creeks cut through mountains and rolling green hills, and streams meandered into hollows.

Embracing the cost of the priesthood

The Ku Klux Klan had a presence in this forgotten corner of the state, even in Fr. Carroll’s no-stoplight parish town called Grasselli, later known as Anmoore. Many of its members saw the Catholic Church as a foreign cult and an intrusion that threatened their settled country ways and established patterns of worship.

The newly ordained priest saw cross burnings with his own eyes. More than once, Fr. Carroll dodged rocks hurled at him outside his new mission church, St. Francis Borgia. Rude words and curses followed him, too, shouted from the open windows of the few passing cars that ground their way up the hillsides.

It seemed the perfect time for the slender Wheeling native to expedite and carry out the directive Bishop John Swint had given him: shutter St. Francis Borgia and the failing mission churches, lock their doors for good, and wait for reassignment to a safer area in West Virginia that might receive the graces the zealous priest was eager to pour out. Until his work was complete, Fr. Carroll was instructed to devote his days to care for the sick and dying as chaplain of St. Mary’s Hospital in Clarksburg.

Priests like Father Carroll, though, see through a different lens. Growing up in a large, devout Catholic family of Irish lineage, “Charlie” came early to see Jesus Christ as a life poured out from the Cross, a libation emptied to the last drop of his Blood. By the time he entered minor seminary at St. Charles College in Catonsville, Maryland, he had begun to believe that unless he accepted the cost of priesthood—unless he embraced the sacred and sacrificial pattern of the Slaughtered Lamb—his vocation would always remain hollow at the core.

When he was ordained on June 10, 1933, he shaped the burden of his priestly identity around a single, uncompromising idea: he would try to become like the mysterious first priest of the Old Testament, Melchizedek: Fr. Carroll would make his own life an offering and a sacrifice. He often told his parishioners, “Love is the complete giving of oneself to the person or persons beloved, without ever counting the cost to self.”

With that understanding of what his priesthood demanded, it was no surprise that Fr. Carroll asked his bishop for permission to remain as the administrator of St. Francis Borgia, despite the threats, isolation, and long odds to establish a Catholic foothold. He asked for the chance to breathe life back into the remote and rural mission churches. Given the time and space, he hoped his prayers, penances, and efforts might help him find common ground and forge relationships with the Protestant community.

And then he told his Bishop Swint one more thing: He wanted to try to raise a mission school—a Catholic home for children scattered across the mountainous county—who were raised in the faith but were cut off and separated by the terrain, where many potholed gravel lanes were virtually impassable, or too treacherous to carry them to a distant Catholic school.

Knowing the young priest’s shepherding heart, Bishop Swint decided to give him a grace period to salvage the bleak situation. He granted his request to remain for a period to try to build a Catholic school and to get to work on the scattered mission churches.

“Let the little children come to me…”

Thereafter, folks far and near began to see an emerging St. John Vianney-like image of poured-out love. The tireless French cure’, named the Patron Saint of Parish Priests by Pope Pius XI in 1929—just four years before Fr. Carroll’s ordination—seemed to rise from his tomb and slip into the skin of Fr. Carroll. As the Cure’ of Ars understood that the youth needed to be catechized, loved, and educated after Robespierre’s bloody Reign of Terror, Fr. Carroll turned to the youth submerged within West Virginia’s rugged landscape for the same reason. Through toil, poverty, and pain, too many children had been amputated from the Catholic Faith.

The Cure’ of Ars, though, had an advantage Fr. Carroll lacked: Vianney’s students each lived in his same small farming village; Fr. Carroll’s hoped-for spiritual children were spread out across mountains and valleys and scattered among families dozens of miles away from his small parish in Grasselli. These were the seemingly forgotten children, many of whom lived in poverty, for whom Fr. Carroll carried an ache in his heart.

He saw Jesus’s command in the Gospel of Matthew at a deeper level: “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.” To Fr. Carroll, these overlooked, poorly educated, and little ones of the hills and hollows were the children Jesus commanded his disciples to permit coming to Him two thousand years later. These children, too, needed the chance to rest their heads against Christ’s Sacred Heart.

But how to get to these children? Practically, Fr. Carroll knew he had to traverse many miles to find, gather, and transport them up and down winding roads and old mining lanes. But that was only one of his problems; he also needed to build a school and find instructors to care for, catechize, and educate the children.

He convinced the diocese to purchase an old casino, which became the brand new St. Francis Borgia School in 1934. Thereafter, he located a band of willing and good-hearted nuns from the Sisters of St. Joseph to instruct the elementary students he prayed would begin to filter in, one by one, to his empty school.

Then, it could be argued, Fr. Carroll had come to his greatest dilemma: he had to find a way to bring children to school. He imagined that a mountain-tested, smaller-sized bus with, hopefully, weather-resistent tires, would do the trick. With all of his remaining funds, he purchased an undersized but sturdy bus-like vehicle—more like an oversized suburban—that he knew an able and experienced bus driver could negotiate up and down roads to get to rural outposts.

With his money depleted, Fr. Carroll could not pay a full-time bus driver.

So he took the wheel.

In the days, years, and decades that followed—through the Depression, World War II, and into the long postwar stretch—the priest with the collar and the steering wheel rose well before dawn to make his way up and down lonely and withering backcountry roads. Along forgotten lanes called Brushy Fork, Corbin Branch, Saltwell, Langtown, and dozens more, he gathered his new students one by one.

Each day, he drove ninety or more miles across Harrison County, grinding up ridgelines and down into hollows to bring children to a Catholic school their parents had never imagined possible. Snow and ice, thick mountain fog, and driving rain made the coal-dusted two-lane roads perilous, but Fr. Carroll—rosary always clutched close—became known as an unfailingly punctual, cheerful, and beloved bus driver.

Within a year of St. Francis Borgia School opening, 76 students filled the classrooms.

A servant who worked constantly for souls

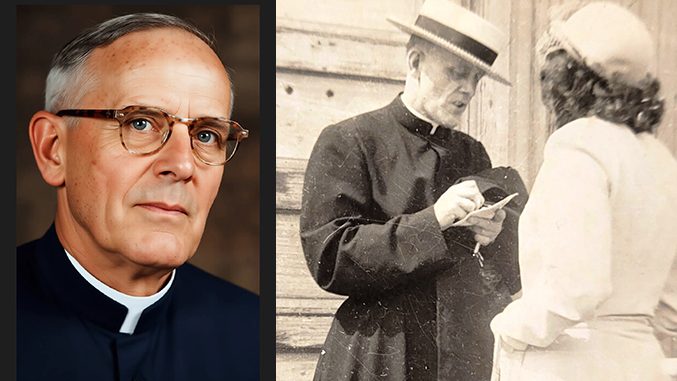

His bus, school, and paternal love are only part of the priest’s tale. The many who love and remember him here regard Fr. Carroll, who died on December 6, 1993, at the age of 89, as the “John Vianney of West Virginia.” They believe him to be a true saint, as deeply holy and sacrificial as any priest they have ever known.

“He was on the run constantly,” said former parishioner James Molina. “I don’t think he slept at all—and if he did, it was just for a few hours. … When I was a young boy, I prayed for Fr. Carroll to be healthy and live forever because he was helping my family and everyone else to such a heroic and selfless degree.”

By the mid-1940s, as the mission churches and his school began to flourish, Fr. Carroll—and his now-famous transport bus—had become widely known among mining families, town mayors, Protestant ministers, shop owners, and nearly everyone else in the region. He was beloved for his sense of humor. Stories lingered of how, as a new priest, he had been forced to create a humble makeshift church out of an abandoned pool hall and saloon—posing for photographs with First Communicants in ivory dresses and suits and ties beneath an old sign that read: “Beer, Fireworks, and Camel Cigarettes.”

Perhaps it was this good-natured spirit that caught the attention of Michael Benedum, an oil wildcatter and, at the time, one of the wealthiest men in America. Bridgeport’s mayor, a Catholic named Joe Deegan, mentioned to Benedum—himself a devout Methodist—that Fr. Carroll dreamed of one day building a new parish by his small new home located at the very heart of the mining communities in Bridgeport.

When Benedum learned that Fr. Carroll was making little headway in building a new parish, he arranged a meeting on a life-changing day in 1953. Benedum had persuaded his Methodist pastor to grant Fr. Carroll first right to purchase the old Bridgeport United Methodist Church off Main Street. An agreement was reached in short order. Fr. Carroll—who for nearly a decade had been celebrating home Masses in his humble Bridgeport dwelling—became the founding pastor of All Saints Catholic Church in 1953, a parish community that remains vibrant today, in 2026.

Patrick Whalen grew up at All Saints, where Fr. Carroll became a fixture for him at the new school and parish. “He had an uncanny ability to always know how his children were doing; it was common and routine for him to give words of praise for accomplishments of all the youth he pastored,” Whalen said. “He had no limits. He was a servant who worked constantly for souls, and ran from church to church to celebrate Masses, confessions, novenas, stations of the Cross, funerals, baptisms, and weddings. He always found the time to make unscheduled visitations to the sick and dying.”

An American Saint?

Because of this heroic witness of priesthood and his tireless spiritual labor on behalf of souls, Bishop Mark Brennan of the Diocese of Wheeling–Charleston has approved the development of a new guild to begin the cause that he—and many others—hope will lead to Father Carroll’s canonization.

This month, two of Fr. Carroll’s former altar boys will travel to California to be certified for the newly formed Center for Sainthood, where the men will be trained in understanding the inner workings of the canonization process. They represent the guild in which Bishop Brennan and countless others believe will result in Fr. Carroll being recognized as an American saint.

Whalen is part of that guild. “Fr. Carroll was filled with what I saw as a divine energy,” he said. “In the midst of his non-stop schedule and traveling through over 900 square miles of his pastorate, he was always ‘present’ to everyone for whatever time he was able to spend with them. Looking back, when he wasn’t traveling in his school bus or car, he seemed to live in his sacristy, in his confessional, and on the altar at Mass.”

Even if he is never canonized, Fr. Carroll is considered by thousands in West Virginia to be one of the most enduring and legendary figures in their state’s history. What he accomplished for God, West Virginians, and the spread of the Catholic faith into formerly hostile areas borders on the incomprehensible.

Within just a few years of being granted a stay by his bishop, Fr. Carroll established St. Francis Borgia as a parish and rebuilt seven mission parishes within three contiguous counties. Two of his early mission churches, in Philippi and Bridgeport, began with the celebration of Masses in homes. These small and intimate Masses led to the current-day parishes, St. Elizabeth and All Saints.

His new school thrived from the start, in large part because of the many thousands of miles he drove each year so that children could be unshackled by remoteness and led to a deeper love for Jesus Christ and the Catholic faith.

A life focused on the Eucharist, the Mass, and the salvation of souls

Meanwhile, Fr. Carroll had begun to break down thick walls and factions in the same manner he split the seams of mountains; he just pushed forward to bring Catholics and Protestants together. He forged friendships with Protestant pastors and cultivated ecumenical bonds with non-Catholics through food drives, outreach efforts, and community gatherings—picnics, Italian meals, and events open to all. His spaghetti dinner became known as the social event of the year throughout the rural mining communities. Believers of all stripes, with calloused hands and large appetites, commingled over plates of pasta as they shared stories from the mines.

Hundreds of folks Fr. Carroll touched in these parts of West Virginia say it was his Christ-like magnanimity, tirelessness, self-deprecating humor, and selflessness that allowed him to conquer calcified and widespread anti-Catholic prejudices. His old parishioners say his life revolved around the Eucharist, the celebration of Mass, and a devoted prayer life. They say that he knew he could not be a priest constantly on the move if he was not first nourished by devotion to Christ and his mission to build the Kingdom of God.

“He reminded us of the wonder and awesome gift we had in our small rural churches,” Molina recalled. “He would tell us, ‘Jesus lives among us and for us in the tabernacle of the altar. He invites us to come, we who are weary and heavily burdened, so He might refresh us.’”

While Fr. Carroll loved his Boston Red Sox, he had no hobbies except, folks here say, his fight for the salvation of souls. He lived simply and almost always turned down gifts or ended up giving them to the poor. When he saw that local children had no extracurricular outlets, he organized a baseball league that would endure for decades. He became widely known for supporting families in need with food, clothing, and financial support with the money that kept coming to him. Townsfolk understood that he was a saintly man who would be a dutiful steward of their resources. Still, because he never asked anyone for money, no one truly knew how he managed to sustain so many of West Virginia’s poor, lonely, and struggling.

He became famous on West Virginia’s roads for taking his trusty bus off hours to pick up anyone he saw stranded on the roadside—no matter who they were or what state they were in.

“My grandfather was an Italian immigrant who worked in the coal mines and couldn’t speak much English,” said Stephen Pishner, an All Saints parishioner in Bridgeport. “He was walking alongside the road one day when Fr. Carroll stopped to give him a ride. My grandfather said he was too dirty and full of soot from the coal. He didn’t want to get on the bus to make it dirty. Fr. Carroll insisted that he get on and let him give him a ride home. He didn’t see a dirty immigrant coal miner; he saw a member of the Body of Christ.”

“He just seemed to know.”

Many here say Fr. Carroll’s interior life of prayer was so intimate—perhaps even mystical—that he possessed foreknowledge of events yet to unfold. Throughout his forty-nine years of priestly service in north-central West Virginia (1933–1982), there were several occasions when he appeared at precisely the moment he was needed, without having been summoned.

“He had a sixth sense about him,” said Al Quagliotti, a former parishioner at Sacred Heart mission church in Brownton. “There are so many stories that I’ve heard where he would show up to give last rites to people who were on death’s door—but no one had called him. He just seemed to know.”

This supernatural vision was inseparable from his priestly heart. It is for this reason that many in the region, whose lives he changed, believe he may one day be canonized a saint and perhaps become known as the Curé of the Appalachians.

“He is our St. John Vianney. Like the holy French priest-saint, he never stopped serving God and souls,” Quagliotti said. “Just as John Vianney transformed a remote and overlooked town that opposed, disliked, and threatened him—Fr. Charles Carroll managed the same in an uncannily similar way.”

“This rural part of West Virginia will never be the same. Fr. Carroll’s legacy of resiliency, intense faith in God, and unrelenting priestly service will be forever woven into the fabric of West Virginia.”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

In a time of mass church closures, this is an inspiring story that I hope more people hear.