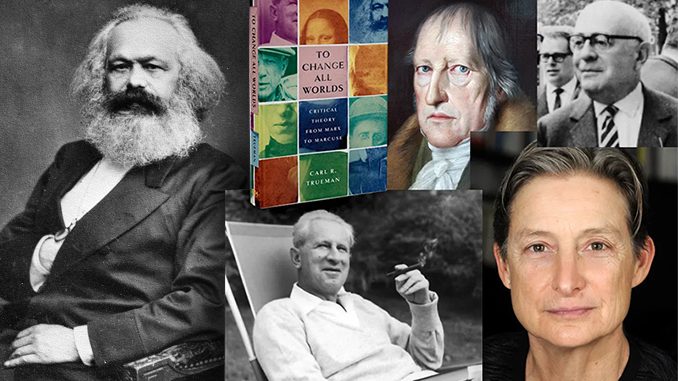

In Carl R. Trueman’s most recent book, titled To Change All Worlds: Critical Theory From Marx to Marcuse (B&H Academic, 2024), the noted scholar and author hones in on the much-discussed but not always well-understood history, foundations, and goals of critical theory.

In doing so, Trueman avoids polemics and hyperbole; rather than looking to argue, he seeks to understand. Charles J. Chaput, OFM Cap., in endorsing the book as “an essential read,” likens Trueman’s work to that of C.S. Lewis and says this book “is a brilliant exploration of critical theory and its impact on the central question we now face as a society: Who and what is a human being?”

I recently corresponded with Dr. Trueman about the book.

CWR: What is critical theory, in a nutshell?

Carl R. Trueman: It is hard to give a concise answer because the term “critical theory” embraces a variety of approaches to the analysis of culture. Some of these are Marxist in origin, such as those associated with the Frankfurt School, whilst others owe more to post-structuralism of a figure such as Michel Foucault.

What all share in common is the intention of destabilizing the status quo, of unmasking the power games and manipulations that lie behind the kind of morality, social practices, and sociological and political categories upon which it depends.

CWR: You assert at the start of this new book that the importance of critical theory is that it is “wrestling with the question of what, if anything, it means to be human…” How does it address basic anthropological questions? And what is lacking in that engagement?

Trueman: One important insight of critical theorists in general is that what it has meant to be human has changed over time and between cultures.

This impulse comes initially from the appropriation of Hegel, and the earlier Hegelian writings of Marx. With critical theorists, this then alters the question from “What is man?” to “Who benefits from defining ‘man’ in this way?” That is a legitimate question, as we know that, for example, a normative understanding of human nature as white was used in the past to justify race-based slavery.

The problem is that this approach also tends to assume that categories such as “human nature” can be reduced to manipulative power relations. That is antithetical to Christian claims about human beings as those made in the image of God as an ontological reality.

CWR: If critical theory is aimed at questions such as, “What is man?”, why is it now known primarily as a neo-Marxist form of political radicalism, wokeism, and reverse racism?

Trueman: As mentioned in the previous answer, critical theory makes the anthropological question an ineradicably political one. Hence, it manifests itself in all areas of the modern world where questions of the manipulative use of social and cultural categories (race, gender, sexuality, and so forth) are important to political discourse.

CWR: The Frankfurt School has, it seems, become a sort of mythical and contentious topic for some when it comes to the origins of critical theory. What are the key facts, especially relating to the mostly privileged and Jewish background of the Frankfurt project?

Trueman: The key figures in the early Frankfurt School, such as Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse, were from very comfortable Jewish backgrounds. That has at least a twofold significance.

First, they were very well-educated and thus deeply read in the Western philosophical tradition. Second, they were nonetheless outsiders in a country that was moving rapidly into the nightmare of Nazism. They were thus both insiders in one sense but also outsiders.

It also meant they were preoccupied with the specific questions of why significant numbers of the working class in Germany supported the nationalist parties rather than the Communists, and how and why the most culturally sophisticated nation on earth was descending into barbarism.

That latter question was not a Marxist monopoly; Thomas Mann addresses it allegorically in his Doctor Faustus. The Frankfurt School found answers by appropriating elements of Hegel and Freud for a revision of the Marxist project that focused not primarily on the economic movement of capital but on notions of consciousness.

They thus focused on analyzing how societies create and manipulate cultural consciousness as a means of understanding why, for example, the working classes freely voted for Hitler and against their own economic interests. One famous aspect of this was Adorno and Horkheimer’s notion of the culture industry, a term they used for the various systems societies use to shape how people think about the world around them.

CWR: The Frankfurt School, you write, “has insightfully framed questions about the human condition and has legitimate concerns about objectifying persons, [but] it does not offer compelling answers to the anthropological questions it raises.” What are some of the questions it got right? And how did it get the answer wrong?

Trueman: The Frankfurt School rightly saw how modern society tends to treat people as things. Mass bureaucracies do this. Employers who see their employees as interchangeable with each other do this. More subtly, the ethics and practices of the sexual revolution that turned sex into a self-directed recreation by making sexual partners into nothing more than instruments for personal satisfaction do this.

And who of us likes being treated in such a way? We are made to treat others—and to be treated by others—as unique persons, as subjects, not objects. On this point, the Frankfurt School shared the same philosophical concerns that we find in Kant and his successors. As Marxists, they see the culprit as capitalism, but from the vantage point of the twenty-first century, we can see that Marxist-based alternatives proved even worse in this regard.

The real problem, as Christians know, does not ultimately lie in some cultural or economic system but rather in the human heart. As fallen creatures, we inevitably tend to treat others as things that exist for our convenience. The answer to that is Christ and his grace, not economic or political revolution.

CWR: Much of your book, of course, explains how we got to where we are now, in 2025. Can you summarize a few of the essential paths or trajectories involved in that philosophical and political journey?

Trueman: Our modern condition is genealogically complicated, but there are few key issues that lie at its heart.

First, there is the move to prioritize inner feelings as definitive of who we are as human beings. We see that starting in the late medieval period and accelerating with figures such as Descartes and Rousseau in subsequent centuries.

Second, as human nature is psychologized, politics shifts from economic to psychological concerns. The early Frankfurt School represents a transitional movement on this point, still committed to the basic Marxist notion of economic capitalism as the problem, but moving attention to the critique of ideas of a culture’s intuitive ways of thinking.

Today, critical theory is largely detached from old-style Marxist thinking about economic class. I would also add that the emergence in the nineteenth century of the rebel or transgressor as a cultural hero has played a significant role too, making perpetual iconoclasm, rather than the transmission of tradition, the vocation of our cultural officer class–artists, educators, politicians, etc.

Significantly, that resonates with a world marked by technological innovation. Thus, the ideology of culture and the ethos of the technological world are symbiotic in creating a world of flux.

CWR: As you have discussed in detail in previous works, the sexual revolution is, at the core, about what it means to be human. How did critical theory inform the sexual revolution decades ago? And how does it continue today?

Trueman: The early Frankfurt School appropriated Freud’s insight that sexual codes are constitutive of society but then historicized that point with a Marxist twist, arguing that specific sexual codes supported specific forms of society and the particular forms of oppression upon which those societies depended.

That opened the way for placing sexual codes at the center of politics: to overthrow capitalism, one had to shatter the sexual codes (monogamous, heterosexual marriages as the foundation of nuclear families) upon which capitalism depended. The economic underpinnings of this may now have been sloughed off, but the idea that sexual codes are oppressive and need to be shattered has remained a staple of modern politics.

CWR: One of many strong qualities of your book is that you take seriously the concerns, rhetoric, and criticisms of the philosophers and theorists you discuss and analyze. Can you talk about your approach and goals in that regard? What sort of mistakes can Christians make in being dismissive or relentlessly polemical when engaging with critical theory?

Trueman: First, I am an intellectual historian, and therefore my primary task with any texts, ideas, or thinkers is to explicate them in historical context.

For me, that is perhaps the most interesting aspect of such work: Can I explain these thinkers in a manner that they themselves would recognize as fair and balanced?

Second, rare is the thinker or idea that is completely wrong at every point. In the book, I use the analogy of ancient heresies. Arius, for example, had a doctrine of God that was ultimately inconsistent with scriptural teaching. But he nonetheless asked an important question: What is the relationship between the Father and the Son? To move to the correct answer on that point requires both understanding why the question is important and why his own answers were wrong.

It is similar with critical theory, which is best approached by Christians as asking good questions that require careful answers, and as providing answers whose weaknesses and problems enable us to find more adequate ones.

To attack (or embrace) critical theory without properly understanding it is disastrous for numerous reasons, perhaps most obviously because such wrongheaded engagement cuts us off from offering a better alternative

CWR: In the conclusion, you reflect on what Christians need to do in refuting critical theory. What are some of the key points you outline and prescribe?

Trueman: Read the sources in context. Understanding what a text means or is doing in context is a necessary precondition to critique. Acknowledge the legitimacy of the questions it asks, but do not be intimidated by that.

When it comes to the central concerns of what it means to be human, how humans should treat each other, and why they fail to do so, Christianity has better answers. Demonstrating the legitimacy of critical theory’s questions has to be accompanied with showing the inadequacy of its proposals and the offering of more adequate alternatives.

(Editor’s note: This essay was published originally on the “What We Need Now” site and is republished here with kind permission.)

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Congratulations to CWR on this lucid discussion with Carl R. Trueman of his new & illuminating, intellectual historian’s account of the pervasive influence of Critical Theory or, rather, of Critical Theories. A nicely balanced approach, acknowledging the validity of questions concerning powerful ideas that shape society yet with a questioning of the frequently superficial, dehumanising answers advocated.

A foundational concept in this discussion is the traditional & widely cited concept of every human being as ‘in the image of God’ (see Genesis 1:27; 9:6). One then has to question where that fits in with Jesus Christ being described as ‘The image of the unseen GOD’ (Colossians 1:15) and it’s consequent attribution to the new nature of every true Christian person from every tribe & situation (Colossians 3:9-11).

If we understand the author of the first few chapters of Genesis as reflecting on the so-called Neolithic Revolution, then Genesis 1 appears as a celebration of the good & godly simple life of ancient first peoples (who, for example, were not ashamed to be naked); with Genesis 2 and 3 then explaining how they lost the plot, disobeyed GOD, became farmers and herders and murderers and city builders with unlimited ungodliness. That approach suggests humans during all of what we call history were not of GOD’s image; not as in Colossians 3:5-8 and all through the New Testament.

The discussion gets even more intriquing if we question: “What actually is GOD’s image?” Since GOD is love and spirit and perfectly holy and good we might think in terms of the one self-existent, supremely right ethical choosing Being [EChB]; with all human persons distinct among other biological species as ethical choosing organisms [EChO]. Only those who, by the virtues of Jesus Christ, freely choose right ethics, fit the Colossians 3:9-11 identification as ‘in GOD’s image’.

Musicians from the US, Nigeria, & New Zealand have recently celebrated this in an amazing, multinational Youtube video praise song: “The Image” by Matt Redman.

Interogating the CT discussion in regards to ‘being in the image of GOD’ seems to open new perspectives.

Thanks again to the two Carls for stimulating insights; blessings from marty

If critical theory asks the right question—”Who and what is a human being?’ (Chaput)—then the recent variant in Marxism is just a special (economic) case of how we estrange ourselves from one another as “we” against “they.” Traditional and now digital tribalism, and all forms of communalism are other cases, including Islam—which sets the transnational and mystical/archaic ummah against all infidels (der al-Islam vs der al-harb). In our multiply-entropic “world,” what are the “better answers” of Christianity?

Here, two points about the “HUMAN PERSON” and about “TRUTH”:

FIRST, rather than an interreligious, or cultural, or geopolitical approach to Islam, what would a personalist and “Christian answer” say about the 7th-century Muhammed event?

“In the history of Islam, the foundational principle of Catholic social doctrine—personal dignity—is evident in an almost random way that has altered world history. Mohammed is credibly portrayed as initially a quiet and peaceable man by nature and a lover of family and children, and as emotionally vulnerable due to the very early deaths of his parents and to his likely epilepsy.

“He later becomes passionately religious as a self-proclaimed prophet open finally to defensive and then aggressive forms of jihad. How much of this tipping point and contradiction can be traced finally to deep humiliations—to violations of his personal dignity? Preaching at the Ka’ba he was routinely scorned by his fellow tribesmen. And when driven from Mecca, and before settling in Medina among protective followers, he first was rejected and even stoned by the villagers of Tiaf.

“Historian John Bagot Glubb speculates on the historical significance of the Meccan rejection. He writes: ‘It is quite possible that this campaign of defamation [!] did the Apostle more good than harm…the hostile remarks which the Qurayish leaders took such trouble to disseminate among the pilgrims may perhaps have served to enhance Mohammed’s importance [!] and to carry his name to distant parts of Arabia’ [!] AND, far beyond Arabia and even into the Third Millennium [!]” (from Beaulieu, “Beyond Secularism and Jihad: A Triangular Inquiry into the Mosque, the Manger & Modernity,” University Press of America, 2012).

SECOND, from Pope Leo XIV, about “peace, justice, and truth,” in his address to the College of Cardinals (May 10, 2025):

“The third word is ‘truth'[!] Truly peaceful relationships cannot be built, also within the international community, apart from truth. Where words take on ambiguous and ambivalent connotations, and the virtual world, with its altered perception of reality, takes over unchecked, it is difficult to build authentic relationships, since the objective and real premises of communication are lacking.

“For her part, the church can never be exempted from speaking the truth about humanity and the world, resorting whenever necessary to blunt language [!] that may initially create misunderstanding. Yet truth can never be separated from charity [and vice versa…], which always has at its root a concern for the life and well-being of every man and woman” (“Peace, Justice, Truth,” In “ONE”, CNEWA, June 2025, 51:2).

The political revolution of the Bolshevik regime was accompanied by a cultural revolution — and from the beginning, this was, above all, a sexual revolution. The goal was not merely to transform institutions, but to redefine human nature itself.

As historian Roberto de Mattei has noted, the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow collaborated with parallel movements in Weimar Germany, such as Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research. In 1929, Wilhelm Reich, a Freudian Marxist, was invited to Moscow to lecture on the abolition of the family and the social liberation of sexual instincts. Reich admired Vera Schmidt’s infamous Detski Dom, where experimental child-rearing incorporated sexual theories, later echoed in Alfred Kinsey’s “research” in the United States. These disturbing ideas — that children are sexual from birth, that moral restraint is repression — laid the groundwork for modern sex education programs endorsed by Western governments and international agencies.

The early Soviet regime initially welcomed this agenda, but Stalin, needing social cohesion, rolled much of it back. Reich and other cultural revolutionaries fled to Germany, and later to the United States, where they seeded what became the Frankfurt School. From prestigious American universities, their theories — now stripped of economic Marxism but fused with Freudian psychology and post-structuralist thought — infiltrated education, law, media, and popular culture.

This is the genealogy of today’s Western sexual revolution. It is not Russia’s heritage, but Russia’s mistake — a mistake that Western progressivism has embraced wholesale. The agenda continues: to dissolve natural law, displace the family, and recast the human person as a pliable social construct. Under the guise of liberation, cultural Marxism offers not emancipation but re-education: language, conscience, and even biology must conform to the new orthodoxy.

This long march through institutions has reached the global stage. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (notably Goal 3.7) now frame access to abortion, contraception, and comprehensive sex education as essential “healthcare” and human rights. Yet this contradicts the natural-law spirit of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which affirmed the family as the “natural and fundamental group unit of society,” prior to the State, and the right of parents to direct the education of their children. The shift from defending human dignity to redefining it — often in ways alien to nature and reason — is a hallmark of the new critical orthodoxy.

Trueman’s book helps us trace how that shift happened — and why recovering a sound anthropology is no longer merely academic. It is a matter of cultural and civilisational survival.

About the mentioned Kinsey “research,” here’s a footnote. The Kinsey Report (1948, 1953), a report pretended to be a statistically valid survey of sexual practices in the West, and then promoted mainstream casualness and pornography under the cover of scientific respectability. The report was later revealed to be based on non-scientific research of a very non-random survey, including willing prison inmates with a disproportionate share of abnormal personalities (Judith Reisman and Edward Eichel, “Kinsey, Sex and Fraud: The Indoctrination of People,” (Huntington House Publishers, 1990)…

The Kinsey “findings” are based on eighteen thousand “sex histories,” all of whom were self-selected volunteers and a quarter to half of whom were prison inmates, and 1,400 of whom were sex offenders, apparently even including nine sex offenders who engaged in direct experimentation on children aged two months to fifteen years. Prostitutes and cohabiting females were classified as married, leading to the claim that a quarter of married women committed adultery. Janice Shaw adds further that Kinsey “was promiscuously bisexual, sado-masochistic, and a decadent voyeur who enjoyed filming his wife having sex with his staff” (see Janice Shaw Crouse, “Kinsey’s Kids,” at http://www.nationalreview.com/comment/crouse200311140923.asp).

Thank you, Peter, for this important clarification on Kinsey’s deeply flawed methodology and moral blind spots. To your crucial historical note, I would add that Kinsey’s “research” was more than pseudoscience—it was also an expression of a deeper philosophical and spiritual rebellion.

As Italian philosopher Massimo Borghesi has argued, the spirit behind much of 20th-century radical thought is Promethean: man rising in defiance against all that is given—especially the figure of the Father. This Promethean impulse runs from Marx (who praised Prometheus as the first “philosophical martyr”) to Nietzsche, and ultimately the Frankfurt School thinkers who gave Kinsey his cultural footing.

Kinsey’s project wasn’t just about data—it was about redefining the human person by dissolving natural law, parental authority, and the moral structure of creation itself. In this sense, his work embodies what Hans Urs von Balthasar called the “Promethean temptation”: not simply to reject God, but to replace Him as the source of meaning and identity.

Author and interviewer present a poignant clear-eyed examination of the “destabilizing” of order and godliness. This trend is much in vogue today and the follower of Christ needs to give convincing answers. The use of simple tested responses carry weight and can change opinions.

The power of listening and asking questions that cause a person to reflect on what they have just proposed can cause the seeker of truth to listen to what God is saying. Opinions are one matter yet, the quest for honesty is the basis for a meaningful and heart changing dialogue.

Kudos for this systematic examination of a topic that will help people to find verity and dispel inexactitude.

“What all share in common is destabilizing the status quo, unmasking power games, manipulations that lie behind the kind of morality” (Precis of Trueman). Except regarding Jürgen Habermas.

If Habermas is frequently quoted by Alasdair MacIntyre, my first acquaintance in After Virtue Habermas cited for recognizing universal norms – then he has added difference plus significance than the others from my perspective as a Thomist.

Jürgen is decidedly Germanic. He apparently has a Lutheran background although he doesn’t claim religious belief. He’s said to be the secularist pope of Marxism. That title indicates his distance from the Jewish members of the Frankfurt School who understandably sought to dismantle the cultural ideological framework that produced Adolf Hitler and Nazism.

Habermas was interviewed 1999 Eduardo Mendieta philosophy prof Penn State. The content of the interview was said to be misinterpreted as a quasi recognition of God and religious belief. Habermas later replied to that presumption in his book Time and Transitions: The reader may form his own judgment.

“Egalitarian universalism, from which sprang the ideas of freedom and social solidarity, of an autonomous conduct of life and emancipation, of the individual morality of conscience, human rights and democracy, is the direct heir of the Judaic ethic of justice and the Christian ethic of love. This legacy, substantially unchanged, has been the object of continual critical appropriation and reinterpretation. To this day, there is no alternative to it. And in light of the current challenges of a postnational constellation, we continue to draw on the substance of this heritage. Everything else is just idle postmodern talk” (Jürgen Habermas Time and Transitions 2006 p 150f originally from 1999 interview)

A useful addendum to this currently highly relevant interview can be found at: https://www.newoxfordreview.org/documents/karl-rahners-baneful-impact-on-theology/

See, especially, its powerful summarizing guidelines.

Also of importance: considerations of what sort of vices spread into The Church when our love and obedience to The WORD OF GOD is corrupted by Christ-demeaning, philosophical theologies – for example, see:

https://www.newoxfordreview.org/no-man-is-an-island/

To respond directly to Olson’s Trueman critical theory enquiry, which theory seeks to destabilize the status quo. Trueman makes two important points, first is to address the criticism in context, the other is that persons are relegated to raw commodities rather than persons.

That apocalyptic Nazism loomed above the minds of the mostly Jewish Frankfurt School is certainly a predominant context that shaped their critiques. Although, it’s not to say that these above ordinary intelligent members did not reveal raw realities, whether what they critiqued had positive value or not. On that score it’s relevant to critical theory that such theory is an equal opportunity proposition. An example is National Socialism, acronym Nazism.

Adolf in Mein Kampf applied critical theory to the Weimar Republic. Former Catholic choir member, onetime aspirant to the priesthood now future Fuhrer critiqued Catholic social services as detrimental to nation building. He assessed the charity given to those in need perpetuated the social disease of apathy to work. Charity, he argued, was a cause of widespread poverty and inertia. Germans were required to recover by grasping their own boot straps. A Nazi intellectual [author journalist William Shirer called Nazis ideologues intellectual gangsters] like philosopher Alfred Rosenberg would point to the success of Nazism in restoring Germany to its former dominance.

Since you and I, most of us here are Catholic or Christian, not to ignore the large non aligned – it behooves us to answer some of these valid critiques made by, let us say Nazi intellectual gangsters. What about charity? Does it, in context or contexts, do more harm than good? For example, the institutionalizing of charity as a form of NGO, a social dimension of the faith. Does government, including religion, create a sociocultural condition that removes the obligation to perform hands-on charitable works by simply submitting a monthly check or government tax? Are we perpetuating the inertia that underlies poverty and spiritual decay? Has socialism Nazi or Marxist crept into and numbed our spirituality? Is it time to reevaluate these programs and make adjustments? Critical theory can be have benefit.

Dear Fr Dr Peter Morello: what a provocative perspective!

“Does government, including religion, create a sociocultural condition that removes the obligation to perform hands-on charitable works by simply submitting a monthly check or government tax? Are we perpetuating the inertia that underlies poverty and spiritual decay?”

Flowing from GOD’s generosity in giving us the priceless gift of Christ, Christian Catholic social ethic has long been established, as in Acts 20:35 –

“. . we must exert ourselves to support the weak, remembering the words of the LORD Jesus, who Himself said:

‘There is more happiness in giving than in receiving'”

The rewards for generosity (and the punishments for lack of it) are starkly presented to us in Matthew 25:31-46.

Recalling that Matthew (Levi) was a professional, acquisitive tax collector makes his chapter 5 presentation of Christ’s Beatitudes especially impactful!

Including: “Give to anyone who asks, and if anyone wants to borrow, do not turn away.” Levi is unmistakeably reborn in Christ!

Also, Luke reports that the first Christians were faithful in obeying Jesus’ instructions to share ALL; as at Acts 2:42-47; 4:32-37; etc.

In Australia, we are proud of our only official Catholic saint – Saint Mary of the Cross MacKillop. She and her sisters gave everything away and lived on whatever charity The LORD provided for them each day. Yet, out of their faithful poverty a wonderful work flowed, saving thousands of souls and providing for numerous needs.

I’d want to rephrase and redirect your: “. . perpetuating the inertia that underlies poverty and spiritual decay.” as:

“. . miserly accumulation of excessive personal wealth that sponsors moral inertia, gross social fractionation, and spiritual morbidly.”

How easy it is for us (even good Catholic Christians) to worship Mammon and to measure our righteousness in terms of our wealth, shares, and property; all the time forgetting that our eternal Judge, The King of Kings, who rules the Heavens and the Earth, lived here as an iterant mendicant, with no permanent address.

We know that without faith no one can please GOD yet Saint James writes that our faith is spiritually dead when we make distinctions between people; we are committing sin and will come under judgment. “. . but the merciful need have no fear of judgment.” see James 1:19 to 2:13.

On the other side of this there is the question, recently raised by Pope Leo XIV, of why work has been made so psychologically unbearable as to break the heart of so many men and women who were ready and eager to contribute to society.

If you want to punish or put pressure on the unemployed you may be doubling the crippling hurt that our dysfunctional society has already loaded on them.

How sad for us, that The Church is sometimes led by the ways of the world, rather than setting a clear example of what GOD’s will on earth looks like.

That Critical Theory has been able to establish and extend a niche for itself is surely, in part, because The Church has not been actively filling that niche.

Yet, I agree with you, dear Fr Peter, its a mistake to believe simply throwing money at people solves society’s problems.

Without a RE-ENLIVENING of genuine Christian faith, led by The Church in CHRIST-obedient mode, it will all avail nothing. Jesus, like Moses, sets before us life and death; so, let us choose Life.

Ever in the love of The Lamb; thanks & blessings from marty

My comment Dr Martin is to remind us all of our requisite for hands on charity. It can be easily done by visiting local nursing homes, clinics which is most efficacious.

Insofar as government for example USA and Medicare, SS should be kept within reason and justice. We are our brother’s keeper, not his enabler.