When asked if she thought that college creative writing programs stifle too many aspiring authors, Flannery O’Connor said that the real problem is that they don’t stifle nearly enough of them. That such programs do an even worse job now than they did in O’Connor’s lifetime is predictable, as are many of the problematic mentalities found within them—mentalities which tend to equate art not with beauty but with angst, expression of a writer’s “inner self,” fashionable “social advocacy,” rebelliousness, “edginess” and other values of leftist ideology, therapeutic culture and pop existentialism.

Few of those who do not take a professional interest in such matters are, however, likely to guess at the existence of a very different tendency found among professors of creative writing—that of treating their own literary efforts like an academic discipline rather than an art. They will attend conferences at which composition is analyzed in as dryly scholarly a way as quantum physics. They will compose fiction for “literary journals” operating on the “peer review” model intended to assure high standards of research in non-fiction scholarship but largely useless as a means of assuring artistic quality, editorial control being in the hands of those chosen for academic rather than artistic accomplishment.

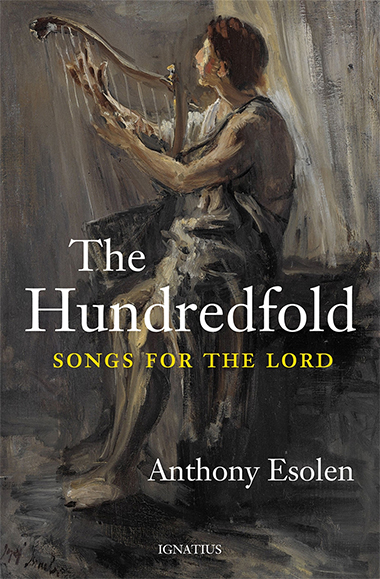

Anthony Esolen’s The Hundredfold presents a direct contrast to such aberrations, representing instead an older tradition which, rather than expecting putative literary artists to be academics, expected teachers of literature—and to some extent, teachers and scholars of the other liberal arts—to themselves have a more artistic literary side and to make at least occasional amateur efforts at artistic composition. Saint Thomas Aquinas wrote some of the church’s most enduring hymns. Saint John Henry Newman’s extensive corpus includes a handful of novels which demonstrate considerable literary skill despite their tendency to be used as vehicles for theological reflection in the manner of a Platonic dialogue. Nobody now reads the poetry of Richard Busby and few recognize his name, yet he taught many of the greatest artistic and scholarly figures of his age, including John Dryden, its leading poet and playwright.

From artistic perspective, The Hundredfold reminds me of the poetry of Samuel Johnson, which was undoubtedly the work of a fine mind yet not a superlative achievement on the level of Johnson’s Dictionary or the poetry of such as Alexander Pope and Walter Scott. To an age accustomed to giving the accolade of “among the best ever” to anything at the better end of the contemporary range, this might seem faint praise. But it is no small thing to compose works which bear comparison to even the lesser writings of a man of Johnson’s stature. This is particularly true when we consider that neither Johnson nor Esolen is primarily a poet, or even primarily a writer in the other artistic genres of drama and of prose fiction. Both are, in large part, moralists, critics and essayists, with Johnson a lexicographer and Esolen a translator.

An easily overlooked fact is that the very pervasiveness of artistic endeavor within the educated circles of the mid-sixteenth to the mid-twentieth century is one of the reasons why that time period produced great literature with remarkable consistency. That volume of great literature was not the consequence only of the existence of a relatively small number of truly brilliant individuals. Handfuls of the truly brilliant exist in all societies. But not all societies provide them with the foundation upon which to begin using and developing their talents.

During the centuries just mentioned, those with literary genius built on a foundation which did not consist solely of classic great works from but also included that of their many contemporaries who had solid literary taste, aimed at a high standard of excellence in their own literary composition and produced literature which was good and solid even if not classic and great. The world of Robert Herrick and Richard Lovelace was also the world of James Shirley and Walter Montagu. To suppose that the former great poets were not positively influenced by reading the works of the latter minor ones, were not positively influenced by personal encounters with the latter and by living in the same literary world with them, would be entirely erroneous. Good, respectable “second tier” works make up no small part of and play no small role in great, living, and developing literary cultures. Not only are such works worthwhile in themselves, but the existence of the living literary culture which they help to create and sustain provides one of the strongest foundations on which the handful of geniuses can develop their talents.

Our society’s often bemoaned (and, admittedly, over exaggerated) lack of good new literature is due only in part to abandonment of solid aesthetic standards. Another problem is that many who are devoted to solid aesthetics are interested solely in reading and teaching the great works of the past, or in promoting and defending solid aesthetics and good literature in didactic and philosophical ways, producing countless articles, volumes, and lectures on the value of the “great books” without ever engaging in an attempt at original artistic composition or encouraging others to do so. Treating literature purely as a subject for the classroom or for philosophical analysis can, however, halt that creation of good new literature just as surely as can abandonment of literary standards. Rebuilding literary culture does not require us to wait for a John Milton or an Anthony Trollope. It does require capable, talented writings to compose and publish good works that can help to get the ball rolling.

At the beginning of his introduction to The Hundredfold, Esolen says that “I don’t know whether anyone in the world of poetry will read it, or, if they do read it, whether they will like it or understand it.” While I cannot claim to be a poet, it is probable that I am more in touch with the contemporary artistic and literary world than anyone else who will review his new book, much of my own writing being for “mainstream” periodicals and much of it concerning artistic and literary matters. And my opinion, for whatever it is worth, is that, despite the need for praise of it to be measured and nuanced, The Hundredfold is a fine, needed, and very welcome artistic achievement.

The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord

By Anthony Esolen

Ignatius Press, 2019

Paperback, 232 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

I’ve been writing what passes for poetry since I was about 8 or 9. (I turn 40 this fall.) None of it has ever been published. Except for the occasional haiku, and a spate of ridiculous teenage angst poems in free verse, it’s all in traditional forms, with at least meter, and often also rhyme, to give it structure. Most of it is on religious subjects, although my favorite poem that I wrote in the past year is not explicitly religious.

If Mr. Baresel were to review the best things I’ve written, I suspect he’d offer a considerably harsher version of the article above; I don’t think I’m as good as Tony Esolen. It’s comforting nonetheless to find someone else advocating for the second tier of writers. A diet of only the best of the best encourages the perception of a gulf between the anointed artistes who produce and the silent masses who consume, which only reinforces and perpetuates our current artistic malaise.

I love this book. My husband and I read a bit of it every night.