It is said that translation is treason, for one language is not another: languages do not simply line up so that one can just swap out words. And so the betrayal of the original source text involved means that much is often lost in translation. It’s one thing to translate between languages close to each other, such as Italian and Spanish, or English and German, but quite another to translate between languages in different families, say, between Semitic languages like Hebrew or Arabic, which employ a triliteral root system and a particular verbal system and Indo-European languages with an altogether different conception of words and its own particular verbal system.

English and Greek are in the same broad family, and yet those learning Greek perceive on day one that the languages are distant cousins, not siblings. Greek uses cases (like the nominative or accusative) to determine function in a sentence (subject and direct object, respectively), whereas English depends on word order. English has an indefinite article (a, an) whereas Greek does not. Greek verbs may not even equate into tenses as we think of them (the several possibilities that get categorized as past, present, and future) but rather employ aspect, which doesn’t do with time what English verbs do. For instance, Greek has a “aorist” form of verbs that has no easy equivalent in English. All that is to say is that those who hear the New Testament in English miss much of what’s going on in the Greek, and those of us who know Greek will still never hear the New Testament the way native speakers in the ancient world could.

And yet translation is a phenomenon that humans have had to engage in since Babel, and it is often successful (though when it fails it’s something between humorous and disastrous, depending on the case). No translation is the original, but an achievement (when well done) in its own right (and so under modern law translations can be copyrighted, even of classic works long in the public domain) that through the miracle of analogy that our intellect is capable of communicates the source to us. Indeed, it’s only by that miracle of analogy that we can translate the reality of God whose simple essence is his existence into human understanding at all. “God is my rock,” says the Psalmist, but we—and the Psalmist back then—both know that God is not literally made of stone, nor finite, nor impersonal, not a creature but the Creator. Rather, by analogy we focus on what is similar between rocks and God: constancy, stability, changelessness. (Of course rocks change over time, but the changes wrought by wind and water are so slow as to be functionally imperceptible.) We know what God is not, and so strip away the crudities from our analogies and then can say positively what God is like. Indeed, we have an imperative to speak of God and translate because God translated himself into our race in the Incarnation and spoke words to us in the person of Jesus. So everyday linguistic translation is a bit like speaking of God who in his Word spoke words to us, and if we can speak of God, then translate we can, and must.

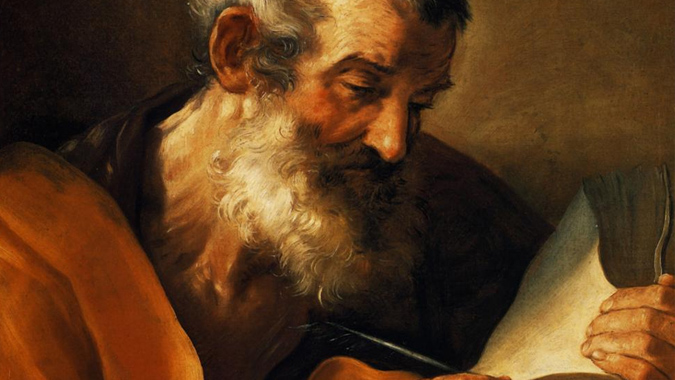

Now Mark is an especially interesting, and challenging, Gospel to translate, for as commentators always note, its Greek is quite rough. German scholars of prior generations like Martin Dibelius and Karl Schmidt regarded the Gospels, especially Mark’s, as Kleinliteratur—klein means “small” and so something like “humble literature” would be a good translation. As compilations of oral traditions and the products of schools, the Gospels were different from literature composed by true authors, Teutonic men of genius like Schiller, Heine, or Goethe.

Now translation isn’t simply trying to get the author’s thoughts from one language into another, but a matter of also respecting form, and trying to bring some sense of the form of the original text being translated, its contours, structure, patterns, verbiage, all in service of an attempt at recreation of rhetorical impact. But that’s the precise difficulty, for (as noted above) languages distant from each other do things differently, and even operate with differing conceptions of time, and indeed reality. Yet respect form we must, for whether Old Testament or New, whether Moses, Matthew, or Paul, the literature of the Bible does not simply convey information (as if it was a tedious compendium of dry truths) but rather tells the story of the People of God. Even prophecy, often poetic in form, presumes the biblical story, and has its own particular narrative substructure. And as such it not only teaches us but moves us, like great stories, speeches, and poems do.

Mark’s Gospel is a weird literary masterpiece. Weird, because on one hand its Greek is indeed rough—it’s not like Homer, Sophocles, or Aeschylus, or even St. Luke or the author of Hebrews—but on the other hand its literary dynamics are amazing. Mark is “A Master of Surprise” (the title of a great little book on the Gospel of Mark by the late Don Juel) who has crafted a narrative that keeps the reader (or hearer in an oral culture) enthralled, on the edge of her seat the whole time. It’s a Gospel of beautiful, striking irony, in which outsiders become insiders and insiders outsiders, faith conquers fear, the identity of the Messiah is a secret, and God hangs on a cross. (I’ve tried my best to capture the brilliance of Mark’s story here.)

Much of that gripping literary dynamism is lost in many modern translations, however, for they endeavor to communicate content, without much regard for form, while also employing different English words for the same Greek word for the (ironic!) sake of keeping the reader’s interest, which also ignores form. For instance, the word schizō appears in Mark’s scene of the Baptism of Our Lord (1:10) and in the verse relating the tearing of the temple veil (15:38). In this latter, most translations render it “tear”: “And the curtain of the temple was torn in two” (RSV, RSV2CE, ESV, etc.). But in the former, it is usually rendered “open”: “immediately [Jesus] saw the heavens opened” (RSV, RSV2CE, ESV, etc). The modern anglophone reader thus misses the linguistic connection in Greek between the two dramatic scenes bookending Jesus’s ministry. In each, the one beginning and the other ending Jesus’s earthly existence in Mark, there is a violent rending of the fabric of the cosmos; the heavens are ripped open and the temple veil before the holy of holies, the very cosmic gate to heaven on earth, is ripped open.

Another example: Mark is known as “the Gospel of the way” because Mark uses the Greek phrase en tē hodō several times in the Gospel (Mark 8:3, 27; 9:33–34, once in each verse; 10:32; 10:46, 52; the word “way” without the full phrase appears in 1:2–3; 2:23; 4:15; 6:8; 10:17; 11:8; 12:14) to indicate discipleship, as in the case of no-longer blind Bartimaeus who got up and “followed” Jesus “on the way” (10:52), his literal actions becoming a symbol and icon of discipleship. But most modern translations will employ several different English phrases for the one Greek phrase again in service of a variety that supposedly keeps the reader’s interest. And so in the Markan verses listed above we find in paraphrastic translations things like “on the path,” “on the road,” “along,” “along the path,” “for the journey,” “by the roadside,” and “along the road” (so the NIV). The reader thus misses the repeated refrain. Similar is the case with a final example, euthus, “immediately,” which occurs forty-one times in Mark’s Gospel. We get variations in many modern translations: “at once,” “right away,” “just then,” “without delay,” and so forth.

Now Michael Pakaluk has provided a new translation of the Gospel of Mark (along with some commentary), titled Memoirs of St. Peter. On one hand, his approach is literalistic: Mark employs the present tense of verbs often, the “historical present,” which (many think) is a rhetorical maneuver designed to keep the reader’s attention through the presentation of a most vivid narrative, as if things are happening now, not then, in the past. And so Pakaluk renders Mark’s present tense verbs with the English present, whereas most translations render them with a past tense verb, since Mark is telling things that happened in the past. On the other hand, the translation reads like a paraphrase similar to famous paraphrases like Eugene Peterson’s The Message.

Here’s a sample, Pakaluk’s translation of the healing of the paralytic (Mark 2:1-12):

When some days had passed, he went into Capernaum again. Word got out—he’s in his house! So many men gathered there that it became impossible to move. There were not even any open spaces around the door.

So he was speaking his message to them. And here they come bringing him a paralyzed man, carried by four men! When they couldn’t bring him through, because of the crowd, they pulled away the roof above the spot where he was. And after they’ve dug up the tiles, they lower the pallet down—where this paralyzed man was lying. So Jesus sees their faith and says to the paralyzed man, “Child, your sins are forgiven.”

There were some scribes sitting there. And they are thinking to themselves, “How can he talk like that? He is blaspheming. Who has the power to forgive sins except God alone?”

So Jesus—who knows immediately in his spirit that this is how they are thinking among themselves—says to them, “Why are you thinking those things? Which is easier, to say to the paralyzed man, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’ or to say, ‘Get up, take your pallet, and walk’?…[sic] But so that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins…[sic]”—now he speaks to the paralytic—“I say to you, get, up, take your pallet, and return home!” The man got up. Without delay, he grabbed the pallet and left—right in front of everyone. The effect was that everyone was overcome with amazement. And they gave glory to God, saying, “We have never seen anything like this.” (pp. 27-28)

Pakaluk has rendered present tense Greek verbs in the English present, while rendering what we usually translate as past (like the aorist) as past. He has also been quite free in using punctuation, especially dashes, though here too there’s a major issue with the translation of ancient texts, which were usually written in continuous script (lectio continua) in all capitals, without any spaces between words and without any punctuation (which was an invention that came about with the invention of the printing press). Translation is treason, and it is always interpretation.

Pakaluk explains his approach as follows:

By trying to make the translation as much like an evocative, spoken narrative as possible, I have found it relatively easy to resolve the two difficulties which confront any translator of Mark. The first has to do with sentence connectives […] Mark is famous for largely limiting himself to one such connective—the simplest one at that—“and” (kai). The majority of his sentences begin with “and.” Translators usually deal with the problem by just leaving the word out. But Mark’s usage makes more sense if we think of how we speak when we tell a story: “So I left my driveway. And I turned around the block. And I saw a man with a pig. And I thought that was strange. So I stopped to ask him about it. And he said….” And so on.

The second difficulty is that Mark varies his verb tenses in apparently unpredictable ways. Sometimes he uses the present tense, sometimes the imperfect, sometimes the “aorist.” Most translations solve this problem by throwing everything into the past tense. And yet this removes the vividness that Mark’s frequent use of the historic present conveys. But when one approaches the text as originally a spoken narrative, one can generally retain Mark’s tense changes. For example: “So I left my driveway. And I turn the corner. And what do I see? I see a man with a pig. And I thought, that was strange. So I stopped and I asked him….” Someone speaking from memory in this way will change tenses to keep the hearer’s attention, but mainly because, as he is speaking “from memory,” he finds it easy to revert to the viewpoint of “what it was like to be there.” (pp. xxiv-xxv)

Memory is rather important here, for Pakaluk believes St. Mark is recording the literal reminisces of St. Peter. St. Peter is the one “speaking from memory in this way” reflecting “what it was like to be there,” because St. Peter was. Mark is understood as a Gospel of urgency and intensity, euthus (“immediately”) again appearing forty-one times, and for Pakaluk it’s not a function of rhetoric or literary construction but history. The Gospel’s immediacy (which Pakaluk makes much of on pp. xiii-xv) is a function of its orality as St. Peter’s memoirs.

Pakaluk thus expends the bulk of his energies in the introduction defending Mark as a Petrine Gospel (pp. xvi-xxviii). He presents an efficient summary of the arguments for Mark’s Gospel being St. Mark’s jottings of St. Peter’s memories that one will find in conservative commentaries of greater rigor and length, presenting the many patristic texts claiming (since the famous testimony of Papias) that St. Mark was St. Peter’s interpreter.

Pakaluk’s translation is worth reading because it will allow the English reader to encounter Mark in fresh ways. The commentary section accompanying each chapter is selective, and often leaves untreated issues that seem to merit treatment.

There are some issues, however. For even as Pakaluk is trying to be literal with his rendering of Greek verbs, he engages in paraphrastic translation which often means he doesn’t present verbal links present in Greek, such as schizō in Mark 1:10 (which he translates there “opened up”) and Mark 15:38 (which he translates there “ripped in two”). Or again in the Markan passage cited above (Mark 2:1-12), he translates euthus as “immediately” in v. 8 but as “Without delay” in v. 12. Nor does he translate en tē hodō (“on the way”) consistently throughout Mark’s Gospel. Now one can make the argument that the varying translations of particular Greek words have the same force: is “immediately” so different from “without delay”? But doing so means the modern reader misses Markan repetition and thus risks missing major Markan motifs.

The fundamental issue is what we are dealing with in the case of Mark’s Gospel: is it literature? A heap of unstrung pearls (as Schmidt and Dibelius would have it)? The rough reminisces of the fisherman from Galilee? In any accounting attention must be paid to the text itself, for whatever Mark’s Gospel ultimately is, it’s a sequence of words on a page. And when we read it those words, we find that Mark’s Gospel is a literary masterpiece, whatever the historical situation of its origin. From there we can certainly engage in historical reconstruction and draw on the Fathers to support this or that hypothesis (St. Augustine, for his part, thought Mark’s Gospel was a mere summary of Matthew’s Gospel). But we must also deal with the form of the text as St. Mark set it down, and go from there.

In sum, although I do wish Pakaluk would have paid more attention to St. Mark’s literary dynamics (and more attention to theological issues in his sections of commentary), I would readily recommend Pakaluk’s translation to those readers lacking Greek who wish to hear Mark’s Gospel in a new key, that they might hear the story in ways that they perceive dynamics they might have otherwise missed reading more stolid translations.

Memoirs of St. Peter: A New Translation of the Gospel According to Mark

By Michael Pakaluk

Regnery Gateway, 2019

Hardcover, 338 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Knowledge without faith is useless, as His Living/‘Way’, Word/Will is radial, and enlightens all ‘honest’ hearts who encounter It, as they seek out the wisdom (Kingdom) of God (Truth). So this saying is still apt for many today.

“You search the Scriptures, because you think that in them you have eternal life; and these are they which testify about me”

I am relatively new to the chaos that I have found on the internet, in how the Science of Interpretation (Hermeneutics), is been used, it’s cold divergence from the living Word of God, with intellectualised nuances. For many it appears to be a game of one-upmanship by the better educated, His compassionate vibrating heart is nowhere to be seen, it appears to be just a mind game for many, but sadly they do not know it.

It is comparable to those who tried to build the Tower of Babel, they cannot understand each other, they are not of one mind, the Mind of Christ, the living Word of God within the heart. The fullness of Gods Inviolate Word is not enough for them, individually they would have more; wanting to be the arbitrators of His revealed Inviolate Will, they would exhaust the treasures in Christ and then still desire more, they are comparable to a man filling a bucket with a hole in it, they retain nothing within the heart.

Faith is trust, trust in His Inviolate Word (Will) as defined by Jesus Christ and the certitude of His teaching. I believe that the questioning of Church teaching is healthy, when the basis of that questioning relates to the conformity of her teaching in relation to Gods Inviolate Word (Will). As only the prior acceptance of the ‘gift’ of Jesus Christ speaking to us through the Gospels, delivers any ground for fruitful discussion, as It will always lead us into the reality of walking His ‘Way’ in humility, as a humble heart is the only place that the on-going transforming action of the Holy Spirit can take place.

“For my gift will become a spring in the man himself, welling up into eternal life.”

The True Divine Mercy Image one of Broken Man given by our Lord Himself to His Church, has the means to call back all of our brother and sisters who are entangled in sinful situations (Those who presently cannot receive the Sacrement of Reconciliation) as it creates an open door, so to say, for them to participate at His Table, in Humility, before God and the Faithful.

As the true image if viewed ‘honestly’ confronts the ego, impelling one to proclaim in humility “Jesus I trust in thee” Trust in God is not just about words, rather it is a movement of the heart, that induces a shared relationship with Him, and underpinning this relationship, is our humility before Him.

Sincerity of heart sits at the base of Christs teachings, and this state (Sincerity) I believe can be ‘ongoing’ even in a soul entangled in a sinful situation (Who cannot receive the full Sacrament of Reconciliation) because it is on the spiritual plane that we encounter (‘Walk’ with) God from moment to moment as in 70×7.

“A bruised reed He will not break and a smouldering wick He will not snuff out”

And neither should the Church, as

“A broken and contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise”

Please consider continuing the theme of brokenness and Divine Mercy via the link

http://www.catholicethos.net/catholic-teaching-assault-amoris-laetitia/#comment-192

kevin your brother

In Christ

Has anyone compared/contrasted Pakaluk’s translation with David Bentley Hart’s “The New Testament” (Yale University Press) ?

I wonder when we will have a translation of the Gospels that really does keep the “roughness” of the Greek originals that enabled the power of Christ’s actions and teachings to “explode” into the hearts and minds of the men and women of the early centuries. Many of the Fathers actually boasted that the literary “roughness” (much derided by many among the Graeco-Roman elite) actually brought out the astonishing marvel of Christ’s life and promises.