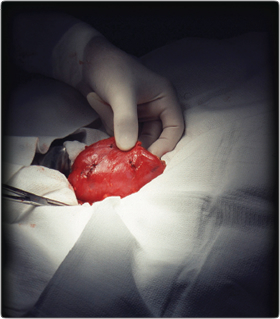

Organ transplantation—the moving of an organ from one body to another—is a relatively new medical procedure. The first successful transplantation in America—whichwas of a kidney—took place in 1954. Today, the most commonly transplanted organs are the kidneys, liver, heart, lungs, pancreas, and intestines.

Organ transplantation—the moving of an organ from one body to another—is a relatively new medical procedure. The first successful transplantation in America—whichwas of a kidney—took place in 1954. Today, the most commonly transplanted organs are the kidneys, liver, heart, lungs, pancreas, and intestines.

The demand for these organs is much greater than the supply. The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), which collects and manages data about every transplant in the United States, maintains the national organ transplant waiting list. As of late May, that list contained 107,729 names. Three quarters of those patients are waiting for kidneys, and they will each wait up to eight years to obtain one. A 2009 study in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology estimated that 46 percent of patients over age 60 waiting for a kidney transplant will die before they receive one. In 2007, for instance, 16,500 Americans received a kidney transplant; nearly 5,000 died while waiting for one.

These numbers have focused the attention of physicians, ethicists, and policymakers on ways to increase the supply of viable organs. While some of the proposed solutions are promising, others, as Dr. John F. Brehany, executive director and ethicist for the Catholic Medical Association, said to CWR, are “inappropriate responses centered on improper notions of the dignity of human life.”

PRESUMED CONSENT

One increasingly popular proposal is for the government to presume that everyone wants his organs harvested if he does not say otherwise in writing. “Presumed consent” would significantly narrow the gap between the approximately nine in 10 people who tell pollsters they favor organ donation and the roughly one in 10 who are both signed up to be organ donors and whose loved ones consent once they die.

At least two dozen countries have adopted presumed consent organ donation systems. In some systems, family members may be required to give consent, while in others family members may veto harvesting even if the donor has consented.

The US has an “opt-in” organ donation system in which one must give consent in order to be designated a donor. All states require that donors make an affirmative statement during their lifetimes of a willingness to donate—by signing a driver’s license, signing up online, or consenting through a health care proxy.

This year, state legislators in New York and Illinois have introduced presumed consent legislation. Cass Sunstein, head of the Obama administration’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, has advocated presumed consent as part of a philosophy of “libertarian paternalism,” elaborated in his popular book Nudge.

University of Pennsylvania bioethicist Arthur Caplan, PhD says that he favors presumed consent. “It is absolutely respectful of voluntary altruism, and it gives most Americans what they say they want—a way to donate. [Presumed consent] doesn’t mean you cannot choose.”

“And we know it works,” he said, noting that waiting lists in countries with “opt-out” systems have been reduced.

Presumed consent places the onus on those who do not want to participate. Libertarians and conservatives are understandably hostile to the idea of government having prerogative over intimate life and death decisions. And so is the Church. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that organ transplantation “is not morally acceptable if the donor or his proxy has not given explicit consent.”

Brehany said presumed consent is rooted in “an improper view of the human person, because it declares that the person’s body is the property of the state, that his organs are the property of the community first.”

TRAFFICKING

Kidneys are the most sought-after organ. And because everybody has two kidneys but needs only one, some policymakers have proposed allowing people to buy and sell them. Iran is the only country that allows kidney selling, and, if its data can be believed, it is the only country that does not suffer from a kidney donor shortage. In most countries, however, buying and selling organs is illegal. The 1984 National Organ Transplantation Act makes it illegal for Americans to buy or sell an organ.

But there is a robust black market for organs. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that one-fifth of the 70,000 kidneys transplanted worldwide every year come from the black market. Stories of organ trafficking are the stuff of suspense thrillers. One of the most startling stories emerged in 2009, when a Federal Bureau of Investigation sting in New Jersey exposed an organ trafficking ring that had operated for more than a decade. An American was charged with conspiring to arrange the sale of an Israeli citizen’s kidney for $160,000. A further corruption probe led to the arrest of 44 people, including state legislators and several rabbis, for money laundering and organ trafficking.

For some, such anecdotes only reinforce the need to legalize organ sales. In an argument similar to those made by advocates of the legalization of drugs and prostitution, organ trade proponents contend that criminalization has not stopped organ sales but only driven it underground, thus creating unsafe and unfair practices for the most vulnerable people involved.

Organ trafficking often involves financial and physical exploitation. The WHO estimated that 10 percent of all transplants in 2007 involved patients from developed countries traveling to poor countries to buy organs. Many donors never receive full payment or remain ignorant of the health risks involved with donation. The Journal of the American Medical Association recently published a study of 305 Indians who sold one of their kidneys. Ninety-six percent said they had done so to pay off debts. But three-quarters remained in debt, and 86 percent said their health seriously declined after the operation.

Caplan doesn’t think a regulated market will develop anytime soon in America, in large part because of opposition by religious groups, including the Catholic Church, and policymakers’ reluctance to open up another front in the culture wars. He also believes that in the world’s richest country huge pay-offs would be necessary.

Writing in the Journal of Economic Perspectives in 2007, Julio Elias and Nobel laureate economist Gary Becker estimated that a payment of $15,000 for living donors would alleviate the shortage of kidneys in the US. There seems to be at least some political support for compensated organ donation. Last year, Sen. Arlen Specter (D-Pennsylvania) circulated a draft bill that would allow government entities to test compensation programs for organ donation. These programs would offer only non-cash compensation, such as funeral expenses for deceased donors and health insurance or tax credits for living donors.

According to the Church, the selling of an organ violates the dignity of the human being because it eliminates the criterion of true charity for making such a donation, and promotes a market system that benefits only those who can pay. Pope John Paul II often said that organ transplants should be undertaken as an “act of self-giving, from the love that gives life.” Speaking to the International Congress on Transplants in 2000, he said “…any procedure which tends to commercialize human organs or to consider them as items for exchange or trade must be considered morally unacceptable, because to use the body as an ‘object’ is to violate the dignity of the human person.” The Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services state that “economic advantages should not accrue to the [organ] donor.”

Specter’s bill hasn’t gotten much traction. But in a society that has already embraced legal markets for human sperm, eggs, and surrogate mothers, one wonders how long it will be before a regulated organ market appears.

The Chinese government has a straightforwardly immoral approach to its organ donor shortage: it just steals organs from members of its highest-in-the-world prison population. According to China’s Deputy Minister of Health, approximately 65 percent of organs used for transplantation come from executed prisoners.

Harvesting organs from prisoners has been discussed in the West (some South Carolina lawmakers want to offer prisoners reduced sentences in exchange for kidneys and bone marrow), but it’s not a solution. Unlike China, America executes only a few dozen prisoners each year. Plus, as Caplan noted, “prisoners are full of infectious diseases like HIV and AIDS,” which make organs unusable.

ALTERING THE DEFINITION OF DEATH

The most troubling and longstanding problem raised by organ transplantation has involved altering the very definition of death, since to transplant a vital organ, the donor’s organs must still be alive. For centuries, prolonged absence of heartbeat and respiration were the criteria for certifying death. In 1968, however, a special committee at Harvard Medical School proposed a definition of death as “brain death” that became widely accepted. Today, determination of “brain death” is used in all 50 states to pronounce patients dead. In brain death donations, the donor is kept on a ventilator to keep blood flowing to organs until they can be removed.

But less than one percent of all deaths involve brain deaths, which has led to further alterations in the definition of death to include “cardiac death.” Because of increasing demand for organ transplants, the federal government has over the past decade challenged medical centers to find novel ways to increase organ transplantation from patients whose hearts have stopped beating but who have not been declared brain dead.

Donation after cardiac death, or “DCD,” increases the pool of eligible donors by allowing physicians to declare a patient to be dead earlier, when the patient’s organs are still healthy. DCD donations tripled between 2002 and 2006 and now account for nearly one in 10 organ transplants in America.

When a person suffers cardiac death, the heart stops beating and the blood stops pumping, which quickly makes vital organs unusable. There is much debate among physicians and ethicists over how much time should elapse between cessation of heart function and declaration of death. A five-minute time span seems to be the emerging norm, but it’s an arbitrary standard and protocols differ. In 2008, the Colorado Children’s Hospital set off intense debate with a federally funded DCD pilot project that involved harvesting hearts from babies 75 seconds after they were taken off life support. After a review, the program re-started with a 120-second wait period.

The same year, New York State received a federal grant to institute a “rapid organ recovery ambulance” to obtain and preserve the organs of people who died of cardiac arrest. This year the Department of Health and Human Services gave $321,000 to two Pittsburgh hospitals for pilot programs to obtain organs from emergency room patients.

Some physicians and ethicists think such practices create perverse incentives for ER workers, who may begin to see patients as prospective organ donors. Dr. Leslie Whetstine, a bioethicist at Ohio’s Walsh University, commented to the Washington Post about the ER organ harvesting program: “there’s a fine line between methods that are pioneering and methods that are predatory. This seems to be in the latter category. It’s ghoulish.”

Caplan is not opposed to DCD, but said, “we need to have a national standard on how it is to be implemented.” Without agreed-upon standards, he believes, the public’s trust will quickly erode. “The public wants to trust that when a doctor says you are dead by cardiac death standards, there’s national agreement about what that means.”

DCD advocates are always careful to stress that physicians won’t check on a patient’s organ-donor status until after death is pronounced and that those involved in transplantation will not participate in end-of-life care or the declaration of death. But instances have already arisen of physicians being accused of hastening the death of disabled patients. Opinion polling suggests fear is widespread. A 2009 online survey conducted by Donate Life America asked 5,100 non-organ donors why they weren’t registered. Fifty-seven percent said they question whether or not a person can recover from brain death, and 50 percent were concerned that doctors will not try as hard to save them if they are known to be an organ donor. In its section on organ donation, the Catechism states, “it is not morally admissible directly to bring about the disabling mutilation or death of a human being, even in order to delay the death of other persons.”

As the baby boomers approach the end of life, more pressure may be placed on new sources of potential donation. The prevalence of organ-destroying diseases like diabetes and hypertension has soared and with it the number of people in need of transplants. Wesley Smith, on his blog Secondhand Smoke, recently wrote that potential targets include “patients with profound cognitive impairments who will remain unconscious or minimally aware for the rest of their lives.” Smith cited an editorial in the prominent scientific journal Nature arguing that “the legal details of declaring death in someone who will never again be the person he or she was should be weighed against the value of giving a full and healthy life to someone who will die without transplant.” He also quoted National Institutes of Health bioethicist F.G. Miller, who argued in the Journal of Medical Ethics that ethical proscription against killing by doctors is “debatable.”

In the long-term, Miller wrote, “the medical profession and society may, and should, be prepared to accept the reality and justifiability of life-terminating acts in medicine in the context of stopping life-sustaining treatment and performing vital organ transplantation.”

ETHICAL SOLUTIONS

But it may not have to. Regenerative medicine, which uses stem cell therapies to create and repair damaged tissue and organs, holds the most promise in addressing the organ shortage. Some researchers hope to use embryonic stem cell research to grow tissue and organs. But so-called “therapeutic cloning” has not advanced despite lavish government funding.

Dr. David Prentice, a leading expert on stem cell research and a senior fellow at the Family Research Council, said to CWR that “embryonic stem cells, simply because of their nature, are unsuited for organ replacement. Their tendency to grow rapidly, rather than repair, makes them hard to control and dangerous for use in transplants.”

The real progress has been seen in therapies derived from adult stem cell research. For one thing, Prentice explained, “repairing the existing, damaged organ in the body replaces the need to do a whole-organ transplant.” Several thousand heart patients have been treated with adult stem cells and subsequently taken off transplant waiting lists.

A study released last December in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology described how stem cells from bone marrow were used to help repair heart damage. And at the annual World Congress on Anti-Aging Medicine & Regenerative Biomedical Technologies last December, Zannos Grekos, MD, director of Cardiac and Vascular Disease for Regenocyte Therapeutic, showed the successful engraftment of stem cells into damaged organs and subsequent regeneration of tissue.

In describing details of the stem cells project, Grekos said, “This is the logical next step in harnessing the regenerative power of stem cells. This will be the next phase in turning science into medicine.”

Grekos highlighted several case studies to illustrate his team’s success with adult stem cells. “We are able to bring patients from a Class IV congestive heart failure status to a Class II status in less than 180 days,” he said. “Three months after treatment, cardiac nuclear scans of the areas treated reveal reversal of damage. We have been able to take patients off the transplant list, and we have been doing it consistently.”

Other scientists and physicians have been treating vascular, pulmonary, and kidney diseases. Athina Kyritsis, MD, chair of Regenocyte’s Medical Advisory Committee, said, “I believe we have only begun to discover what adult stem cells can accomplish in altering the course of diseases currently believed to be untreatable with not only improved clinical results, but also a financial savings to society.”

Other potential stem cell solutions include a 3-D biological printer that—somewhat like an inkjet printer but with an extra dimension—coaxes stem cells extracted from adult bone marrow and fat into many other types of cells by applying appropriate growth factors. According to The Economist, once clinical trials are complete, perhaps in five years, the new bio printers could “be used to create the networks of blood vessels needed to sustain larger printed organs, like kidneys, livers, and hearts.”

All my interviewees—Caplan, Brehany, and Prentice—consider adult stem cell therapy the long-term solution to the organ shortage problem. It would appear that the solutions consistent with the Catholic understanding of the human person are also the ones that show the most promise.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.