I recently returned from visiting Croatia, where a controversial referendum was held on December 1 amending the constitution to define marriage as a union of a man and a woman. The results surprised many foreign observers: 66 percent of voters were in favor of the proposal.

Though some media outlets asserted that the campaign in support of the resolution was organized and promoted by “reactionary” officials from the Catholic Church, the truth is that the referendum and its results were all entirely the handiwork of grass-roots activists—mothers and fathers, young couples, and the mass mobilization of thousands of families of different faiths. In short, it was lay people—not priests or religious—who orchestrated it all.

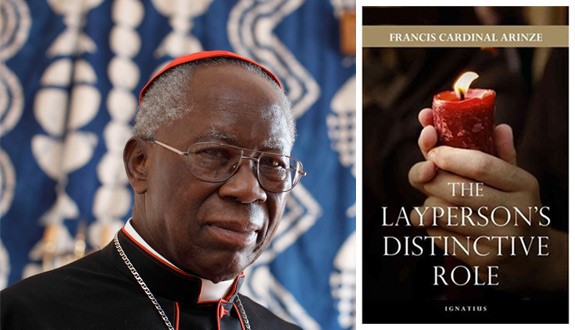

Cardinal Francis Arinze’s new book, The Layperson’s Distinctive Role, explores precisely this topic: the role of lay people in politics, society, and the Church. In this, it is a timely and necessary book.

Arinze begins by explaining that the word “laity” comes from the Ancient Greek word for people, laos, and describes some of the earliest forms of Christian communities that arose in the wake of Our Lord’s Passion and Resurrection. However, he stops short of offering a historical survey of the rise of religious orders and communities and, instead, focuses on the key documents of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) that clarified the duty, role, and apostolate of the lay faithful “in the Church and in the world.”

Arinze starts with a look at the main Church documents in which the role of the laity has been defined, clarified, and elaborated upon. These documents include those from the Council such as Gaudium et Spes, the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium, and the Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity Apostolicam Actuositatem. In addition, he considers various papal documents such as Pope Paul VI’s 1974 exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi and Blessed John Paul II’s apostolic exhortation Christifideles Laici, issued after the 1987 Synod of Bishops on the vocation and mission of the lay faithful. These documents provide “the major orientation for our times on the role of the lay faithful in the Church and in the world,” according to Arinze.

Of course, this understanding of the layperson is quite modern. For centuries, the common assumption was that priests and religious were called to lives of sanctity, with little focus on the laity. But, in recent decades, especially at the Council, the Church began to emphasize that the call to holiness was for everyone—the clergy, religious, and laity. As Arinze points out, “[e]veryone in the Church shares in the Church’s mission according to each person’s vocation.” And this can be through the vocation to Holy Orders, the vocation to the consecrated life, or the heroic vocation of the lay faithful. It is not insignificant to note that 99.9 percent of the Church’s members belong to this latter category.

It’s true that it took a long time for most people to accept this new understanding of the role and duty of the lay faithful in the life of the Church. There was more than a little resistance. Religious institutions like Opus Dei, for example—whose special charism focuses on the lay faithful—were initially viewed with much suspicion: their message that even laypeople could aspire to sanctity, and that all walks of life and all roles in society were important for the life of the Church, seemed scandalous.

But by drawing on Church documents and offering a few exegetical comments on certain passages from the Gospels, Arinze does us a favor, helping to clarify exactly how the Church sees my role as a lay person within the life of the Church and in secular society. I finished it feeling encouraged—even emboldened—to go out and participate more fully in, say, the life of my local community and neighborhood, and to help bring religious faith back to the public square, from which it has been banished over the last several decades.

Arinze spends quite a bit of time considering the public or political realm. On the one hand, he points out that although it is the lay faithful that have the duty to work in the world of politics and effect changes for the common good and the good of society, the Church also has a role here—an indirect duty, he says—“to contribute to the purification of reason and the reawakening of moral forces.” To be sure, the Church’s priests and officials have done this, in some countries more than in others, often sacrificing their own lives in defense of a higher good.

But he emphasizes that the laity have a unique role to play in the broader and long-term “evangelization of politics and government.” By this, Arinze means simply that the lay faithful should strive continually to bring “the spirit of Christ into the various spheres of the secular order.” He elaborates on this point further: “This is another way of saying that politics and government should respect God’s plan, should obey the natural law.”

Such a message may surprise some of us, accustomed as we are to the exaggerated division between church and state that exists in the United States. Mind, Arinze is not advocating a reunification of church and state or some form of “Catholic integralism”; far from it. He is simply reminding the lay faithful that they have a duty to live the spirit of Christ in every sphere of human activity, to be an alter Christus and essentially to sanctify the secular world and do the work of apostolate.

Actually, some might find Arinze’s treatment of the nature of “apostolate” a bit wanting. He says quite simply that “[b]y apostolate, we mean the mission of the Church, the motive of Christ in founding his Church. It is to spread the Good News of salvation in Jesus Christ.” The cardinal could have gone further on this point; for instance, he could easily—and for our great profit—have made reference to the seminal work L’Âme de Tout Apostolate (The Soul of the Apostolate) by Jean-Baptiste Chautard. Beginning with its first edition in 1907, that work explained to generations of faithful how prayer is central to apostolic work and how “the preaching of the fundamentals of the Faith by people imbued with the interior life” was one of the most effective ways to “save” the world.

Because Arinze cites so many passages of different Church documents to establish the authority of things, I found the book at times a bit repetitive. But this may have been unavoidable as the different documents referred to necessarily overlap, with one building on the intimations of a preceding one or elaborating further on a theme mentioned previously.

For a more detailed treatment of what the lay vocation entails in the modern world, one could turn to Living the Call: An Introduction to the Lay Vocation, written by Michael Novak and William E. Simon, Jr. and published in 2011. That book meanders through the lives of various exemplary people, provides numerous vignettes of how lay people can deepen their inner lives, and offers tips on how to better be in the presence of God. But for a very brief and very sound introduction to the role of the layperson and his distinctive duty in the world and in the life of the Church, Arinze’s book is ideal.

Laypeople are far more important than many of us may think. They have a great and grave responsibility to help the Church, complementing it in its activities and in its sacramental actions, but also supporting and sharing its message in those spheres of life in which laypersons can have a great impact. And through his activities, the layperson can help sanctify the whole of life, no matter what his station in life.

We should remember this as we go about our day to day activities—and always keep in mind not just a sense of divine filiation, but a sense of responsibility. We are called, after all, to be saints.

The Layperson’s Distinctive Role

Francis Cardinal Arinze

Ignatius Press, 2013

118 pages, $9.95

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.