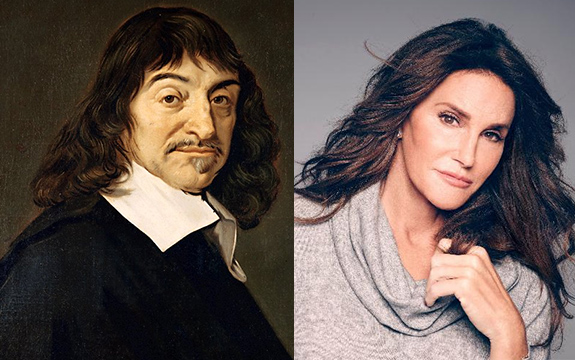

The seventeenth century philosopher, Rene Descartes, is best remembered for his pithy little aphorism, “I think, therefore I am.” His point was profound, though not entirely original. St. Augustine made essentially the same point twelve hundred years earlier: “Even if I am deceived, I am. For he who does not exist cannot be deceived” (City of God, 11.26.). Augustine’s and Descartes’ point was that, in the very act of thinking, we have proof of ourselves—of our own unified personal identity. We can be wrong about the external world. We can even be deceived that we have a body. But the thinker cannot be deceived about his very existence since the very act of thinking entails that I—the person who is thinking this thought—exists.

Contemporary trends have extended—and bungled—this Cartesian insight. And it has done so for reasons that are all too predictable. Descartes’ and Augustine’s point was that there is an almost ineffable difference between the human soul and the rest of the world. The soul is known directly by an immediate act of intuition. The world is external. We cannot know it directly. We could even conceivably be wrong that there is an external world. But each of us cannot be wrong that our individual self—our “I”—exists.

We now live in an era when people want to extend what we must know for certain well beyond the boundaries of the self. They insist that merely believing something can make it true. If you are a white female president of a state NAACP and you really just feel that you are black, well, then you are black. If you are a male one-time athlete turned reality TV show participant named Bruce and you decide that you simply feel female—well, then you can call yourself Kaitlyn. To hijack Shakespeare, “There’s nothing male or female (or black or white) but thinking makes it so.”

The hyper-Cartesian attitude to gender identity or race should not surprise us. For the last three or four centuries, the upshot of our philosophy has been to put all truths “in the heads” of human beings rather than “out there in the world.” Classical philosophers such Aristotle, Augustine and Aquinas all assumed that what we call “truth” is a measure of the correspondence between what we believe and what is out there in the world. If what we believe does not correspond to what is really “out there in the world,” then we have not arrived at the truth.

But modern philosophy has generally fought against this common sense view of the meaning of “truth.” John Locke began the new project by putting ideas “in the head”—making them a subjective thing rather than a measure of external reality. Hobbes said “truth” was just a correspondence of words. More recent philosophers have pretty much followed the same trend, either making “truth” a purely subjective quantity or entirely abandoning the very idea of truth.

The process—what I call the demise of the reality principle—has fairly infected almost every field of thought. Our “moralists” have insisted for two or three centuries now that morality is purely subjective, relative, a human construction. We have been told by our political philosophers that society and the state are products of a social contract and that all human institutions are artificial rather than the natural expression of our human nature, as Aristotle or Aquinas would have insisted. Like the truths of morality, we can revise any of these—abolish the family, for example. Even the last bastion of objective truth—the physical sciences—has been under assault during the last few decades by postmodern philosophers of science who insist that even scientific truths are constructed.

There is little left in our culture of the idea of objective truth. There is nothing that cannot be “remade” by simply thinking it so. Why should we have assumed that the process of subjectification would stop at the gender line?

Now, here is where Descartes got it wrong—and how his philosophy unwittingly contributed to the contemporary gender-subjective mindset. Classical thought—the thought of Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas and many others up to the modern era—always taught that the identity of a person is intimately bound up with his body. The human person is a composite of the soul and the body. The soul, for Aristotle and Aquinas, was the “substantial form of the body.” What this meant is that the soul is not an entirely separate substance that exists independently of the body. There can be no unified life without the soul, but the person is identified and individuated by his body. We call this the “hylomorphic” theory of the person: the human person is a composite of body and soul. There is no “person” without both.

Descartes abruptly rejected this hylomorphic understanding of the person and, in doing so, led to a whole host of typically “modern” philosophical problems—e.g. the “mind/body problem,” the free will problem. He fostered the myth that soul and body were two distinct substances that interact with each other. This made the body something external to the soul—a mere instrument of the soul. We may make of the body whatever we wish, but the real truths are the truths of the mind. Insert this philosophy into the postmodern context and what do we find? What a person is is whatever he think he is. His body—his race, his gender – is irrelevant.

The demise of the reality principle is simply an outworking of modernity’s abandonment of an understanding of the world according to which we are creatures, not Creators. It is a product of our collective cultural insistence not only that we make the rules—but that we make the truth.

The problem with this whole set of developments is that, the more this whole subjectification process continues, the more it makes itself meaningless. We need something outside the self as a referent to what we are talking about in order for our feelings or thoughts to make sense. If truth is only a correspondence between words, as Hobbes thought, what do these words mean? They have to refer to something beyond the words—something objective, outside the mind. Otherwise, they can’t correspond in any way—in which case we will be forced to jettison the very idea of Truth.

This same process is underway in the context of the sex-and-gender debates. There must be an objective reality—embodied in the physical reality of sex—for gender to make sense. When we inflate the currency of gender, we inevitably must devalue the currency of sex. Yet this is self-defeating because gender is ultimately pleonastic on sex. As what it means to be “male” and “female” disintegrates, so too, must the idea of gender. We can only make sense of Bruce Jenner’s desire to identify as a female as long as there remains a substantial number of human beings who actually instantiate the characteristic of “female-ness.”

Permitting people to assign themselves their gender is a bit like income redistribution in this respect. As Margaret Thatcher might have said, “Sooner or later you run out of other people’s gender.”

Related on CWR: “The History, Enemies, and Importance of Natural Law” (May 10, 2016): An interview with Dr. John Lawrence Hill

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.