Recently, I was directed to an article by conservative Evangelical author and activist Katy Faust entitled “No Time for Friendly Fire: Why Catholics and Evangelicals Need Each Other Now More Than Ever.” I confess that I was planning on hating it; I presumed Ms. Faust would urge Catholics and Protestants to set aside their theological disagreements in order to focus on cultural and political battles, such as those on abortion, transgenderism, or parental rights. I’ve heard more or less the same appeal from other Protestants, who have quite directly told me I should stop writing books and articles aimed at Protestants and instead focus exclusively on politics and the culture war, because that is more pressing and consequential than ecumenical debate.

Thankfully, that is not what Ms. Faust argues. “We have,” she writes, “significant doctrinal differences, worth discussing, worth debating, even worth worshiping separately over.” Yet, she observes, something seems to have recently changed: Evangelicals and Catholics are “calling each other stupid. Hypocritical. There’s slander, misrepresentation, and clickbait-level caricatures.”

This, Ms. Faust rightly avers, is contemptible and self-destructive, especially when cultural Christianity and the number of self-identifying Christians are in decline.

Admittedly, as someone who largely avoids social media, I am not well acquainted with what Ms. Faust is referring to when she describes increasing tensions between Protestants and Catholics. Indeed, in the almost fifteen years since I left the Reformed tradition to become Catholic, I have regularly witnessed my fair share of ad hominems directed at yours truly. And I’m sure there are Catholics out there (sadly) doing much the same towards Protestants. What’s so different now?

Nevertheless, Ms. Faust has a good point, and she makes it well. Inter-Christian differences matter and are worth debating. “But we must refuse to destroy one another in the process,” she writes. Indeed, there was a time when Protestants and Catholics did try to destroy each other, and their battles almost ended Christian Europe, as is quite viscerally described in the 1938 novel The Wedding of Magdeburg, recently published in English for the first time by Ignatius Press.

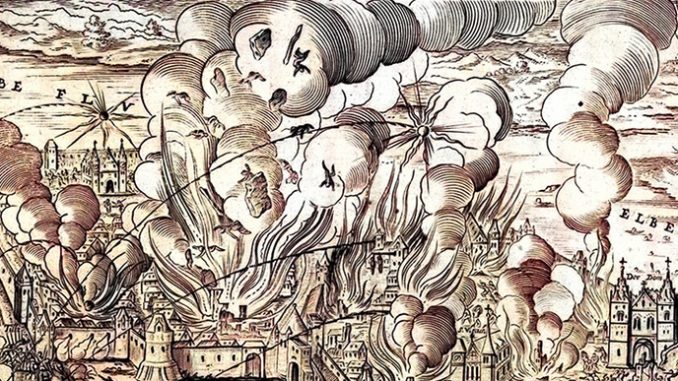

Written in the days leading up to the Second World War by the German convert to Catholicism and Nobel Prize nominee Gertrud von le Fort, The Wedding of Magdeburg describes the siege and sacking of the Free Imperial City of Magdeburg. The city was a prominent municipality in the Holy Roman Empire, whose predominantly Protestant cities rebelled against their Catholic emperor. Almost four hundred years ago, in spring 1631, an imperial army under the overall command of “the monk in armor,” Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, besieged the rebellious city.

The title carries two meanings. The novel depicts the political and military developments of this tragedy, which resulted in the deaths of 25,000 of the city’s inhabitants (most of them civilians), while also describing the romantic relationship of a young bride jilted on the eve of her nuptials by her fiance, who had been commissioned by the city to act as a diplomat with the approaching army.

Thus it is the story not only of a young German couple whose wedding is delayed by political events, but the “wedding” of the imperial army and its “bride”—the city of Magdeburg—whose identity and even architecture was pregnant with bridal connotations.

In Von le Fort’s most capable hands, the story of the sack of Magdeburg is told with excellent anticipatory drama. And yet in another sense, because this is historical fiction largely based on real events, it makes it all the more difficult to read. We know the impending disaster that awaits the beautiful bride of Magdeburg, whose historic buildings and noble people will soon be wiped out. Terrifyingly, that reality is unavoidable; the protagonists, no matter how courageous, are incapable of preventing one of the greatest tragedies of the Thirty Years’ War.

If you know anything about that terrible conflict, you know there are many tragedies to tell. Somewhere between 4.5 and 8 million soldiers and civilians died because of battle, famine, or disease. Some regions of Germany experienced population declines of over fifty percent. That kind of slaughter is difficult to imagine for our contemporary minds. By way of comparison, the suffering and starvation currently endured by Palestinians in the Gaza Strip has not reached anywhere close to the level of devastation inflicted upon what is now Germany.

This is all the more mournful because the people killing each other professed the same Jesus as Lord. Practically all of them even professed some of the same creeds, such as Nicaea and Chalcedon. They prayed to the same God, and then mercilessly slaughtered one another in the very name of that God. Von Le Fort has the Count of Tilly ask:

Did Mary not want a war of religion? Would she rather endure the pain of religious division instead?… He suddenly felt as though he’d misunderstood the Blessed Virgin his entire life. For Mary did not triumph with sword in hand, Mary triumphed with the sword in her heart; she achieved victory through the suffering love of her Divine Son!

It’s a provocative question. Surely, Jesus and Mary could not approve of Christians massacring each other. That this happened while the Ottoman Turks were encroaching into Christendom makes this all the more disturbing. Belgrade fell to the Turks ten years before the sack of Magdeburg; Buda, in turn, fell twenty years later. How could Christians be so foolish?

Through certainly a faithfully rendered historical novel about the Thirty Years’ War, Von Le Fort also obviously intended for this book to speak to modernity’s turn away from God.

She writes:

Where yesterday there had been a holy power to restrain the naked powers of the world, tomorrow there will be only those naked powers, with nothing more to restrain them — who indeed could restrain them, if Holy Religion is no longer able to do so? The nations will turn on one another like the ravenous beasts of the forest, and Holy Religion will stand by and watch, her hands bound. She will be locked up in the narrow confines of the church walls, or in the quiet chambers of the heart, and perhaps one day there will be an attempt to drive her out of these places as well…. Eventually there will be nothing on earth more embattled and more imperiled than Holy Religion!”

The aftermath of that miserable, decades-long conflict inaugurated precisely this development, as Enlightenment philosophes looked with disgust at the seemingly useless bloodshed done in the name of religion and Christianity. States became increasingly secular and detached from their religious heritage. In Nazi Germany, where Von Le Fort wrote, Christianity was dramatically muzzled. Now, in much of Europe, it is on life support.

When non-Christians, whatever their particular variety, witness Protestants and Catholics treating each other with shameful disrespect, it will certainly harm our collective witness. Regardless of how much they know about Christianity, they know we are all in some sense on the “same team.” Caustic and uncharitable sniping among us thus undermines our attempts to share a Gospel message that is supposed to evince a transcendent love.

That’s especially the case given that Protestants and Catholics are often trying to effect the same outcomes, based ultimately on a Christian paradigm of love. We oppose abortion because God loves children. We oppose transgenderism because God loves us as He created us. Our opponents claim these beliefs are motivated by hatred and bigotry. Let’s not give them ammunition. As Faust argues: “Let’s debate with respect, but lock arms where it counts.”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

“Belgrade fell to the Turks ten years before the sack of Magdeburg; Buda, in turn, fell twenty years later. How could Christians be so foolish?”

The author has confused the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

It’s altogether possible that we will soon be persecuted alongside our “separated brethren “ so it may be well to get to know them.

I agree Br. jacques.

It’s complicated. Historically change of suzerainty over Bohemia from Habsburg Catholic Emperor Ferdinand by Protestant Frederick of the Palatinate upset the balance of power drawing in Catholic v Protestant combatants. Although Catholic France and Lutheran Sweden had territorial interests in opposition to the Austrian Habsburgs and their German and Spanish counterparts. England sided with Lutheran Prussia.

William Makepeace Thackeray in his novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon, an historical satire set against the backdrop of that War, speaks as a commenter saying in all his research of historical accounts, consult of philosophers he could never understand the reason for the war. Catholics, German and Spanish had the war won until Sweden’s Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden intervened and turned the tide.

Although the doctrinal war between Catholicism and Protestantism is more clearly defined by the issues transgenderism and abortion. Chalk implores we lock arms, a noble sentiment with possibilities given conditions.

Fortunately, the Ignatius Press book club with Father Fesio, editor Vivienne Dudro, and Joseph Pearce has been hosting this book discussion every week. Thank you for this alert. I will run to get caught up with this read.

How did you hear about the book club? Thank you.

I’m not sure if “outsiders” think all Christians are on the same team. Certainly though, the early Church pulled no punches in defeating the threat of gnosticism, regardless of the existential threat posed by outsiders. In the end, the terminal threat is the one that can distort the faith. The Thirty Years War concluded with the triumph of the idea that religion is determined by civil society. That is indeed an existential threat to Christianity, one worth quarrelling over.