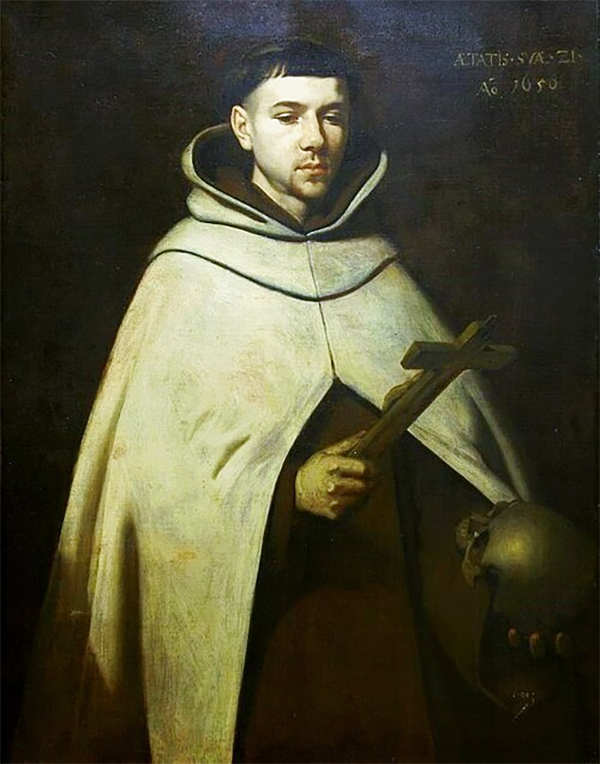

John of the Cross, whose feast day is celebrated on December 14th, has been granted many titles since his death: reformer of the Carmelite order, master of Spanish classical poetry, canonized saint, and Doctor of the Church.

Yet his life was full of seeming contradictions, paradoxes that only make sense in the light of Christ.

Early life

The man we call John of the Cross was born in Fontiveros, Spain, and was given the name Juan de Yepes y Álvarez (1542-1591) at birth. His devout parents had married for love and had three sons. John was the youngest.

John’s father was disowned by his wealthy family when he married a poor but beautiful young woman. He tried to support his wife and sons through weaving. But his father’s health suffered due to their poverty and lack of food, and he died when John was about five years old.

John’s mother took over the family business to support herself and her sons. But her oldest son became a rebellious teenager, and her middle son died, apparently from malnutrition. She uprooted her small family and moved to Medina del Campo, a bustling trade city.

In Medina del Campo, young John’s life improved. He was taught for free at a school for poor children and learned to read and write in just a few days. Yet he did not seem to have an aptitude for the practical trades his instructors tried to teach him.

Fortunately, the administrator of a hospital noticed the sensitive teenager and offered him a job as a nurse. It was an excellent fit. John’s compassion for his patients overcame his distaste for the smelly, messy aspects of nursing. Although the pay was poor and his own living conditions were worse than those of his patients, he also had time for prayer. Gradually, he realized that God was not calling him to a career as a nurse but to enter religious life.

Friar John of the Cross

He asked to be admitted to a nearby Carmelite community as a religious brother, was accepted, and took the name in religious life of John of St. Matthias.

John completed his novitiate and was sent to a Carmelite college so that he could be ordained to the priesthood. He impressed his professors through his careful attention to his studies and his thoughtful theological reflections. John also felt called to live a more penitential life than was practiced by the other members of his community. With permission from his superiors, he began practicing additional penances, such as prayer vigils and fasting. Some of the friars resented him for this reason and snubbed him. He quietly accepted his loneliness as a God-given opportunity for greater solitude.

John was twenty-five years old when he met the famous Madre Teresa of Ávila, the founder of the Discalced Carmelite order. Although he was a quiet man and had fragile health, Saint Teresa immediately recognized John as the man who could bring the same reforms to the men’s branch of the Carmelite order that she had begun to implement among the Carmelite nuns.

Now known as Friar John of the Cross, he and a few companions began to live out the Carmelite rule in a rigorous way. Lay Catholics who lived nearby and who heard him preach were moved by his gentleness and spiritual depth. As the years passed, Madre Teresa often turned to John for spiritual advice and for help in founding new Carmelite communities. However, as the reform of the Carmelite order spread throughout Spain, so did resentment by Carmelites who saw no need for reform.

For a few years, tensions between the Carmelites and the Discalced Carmelites increased, with contradictory orders being issued by leaders of each group, various bishops, the Spanish king, and the pope’s representatives. In 1577, a leading bishop who had supported the Carmelite reform died. Taking advantage of the fact that the Discalced had lost a powerful protector, a group of Carmelite friars broke into John’s dwelling in the middle of the night and kidnapped him. They charged him with being disobedient to the order of a Carmelite superior—although John had been obedient to the orders of the papal nuncio—and imprisoned him in their community in Toledo.

The dark night of the soul

John was placed in a small, dark, smelly, unheated cell, received weekly beatings from members of the community as “discipline,” and was given only scraps of food to eat. During those long months of captivity, he experienced what he later called a “dark night of the soul,” a period of spiritual dryness in which God seemed to be absent. Deprived of consolation even in prayer, John might have given up hope, renounced the Carmelite reform, or become a bitter, angry man.

Instead, he composed The Spiritual Canticle, a love poem between a soul and Jesus Christ, modeled on the Biblical book, Song of Songs. As he later told others, it was precisely through this experience of apparent abandonment by both God and man that his faith in God deepened.

When John realized that he was slowly dying from the mistreatment he was experiencing, he decided that he had to escape. His new jailer had been moved by John’s kindness and was lenient. John surreptitiously used a piece of thread to measure the drop from a balcony to a nearby wall and decided he could survive the fall. He secretly loosened the screws on the door of his cell. He tore his blanket into strips and sewed them together to make a rope.

Then, in the middle of the night, he pushed open the door to his cell, which fell and made a tremendous noise. Surprisingly, no one came to investigate. Then, he used his homemade rope to drop himself down from a balcony onto the wall of the monastery. He jumped outside the wall and wandered through the streets as fast as he could until he reached a community of Discalced Carmelite nuns. The nuns were speechless when they saw the emaciated, sickly man, and they helped him recover from his ordeal.

Leadership and declining health

John returned to his labors among the Discalced Carmelites. During this period, he encouraged the order’s nuns in their lives of prayer and mortification, and he wrote some of his greatest spiritual works to help others grow deeper in their love of the Lord. He taught the friars how to live out their vocation through his example of personal mortification, his generosity with the poor, and his gentle but firm leadership. While he loved spending hours in nature and in prayer, he also spent hours among his friars during their common recreation periods and led them in long, fruitful conversations.

John had uncomplainingly accepted assignments in Carmelite communities in southern Spain for years, even though that meant he was far away from his beloved mother and brother. Now he was given important administrative positions throughout Spain and was able to visit his family again. Since Saint Teresa had died, John became an influential leader in the order and worked to ensure that the Discalced Carmelites remained focused on prayer and contemplation, not on preaching or the service of others, as good as those other acts might be.

As a superior, John was forced to correct some of his friars, and not all of them peacefully accepted his correction. One Carmelite superior publicly insinuated that John was guilty of inappropriate behavior with nuns. As his false allegations spread, John refused, out of charity, to criticize his detractor.

At the same time, John’s health began to suffer. His superiors ordered him to go to a Discalced community to rest and receive medical treatment. Given the choice between a monastery at Baeza, where he had many friends, and a monastery at Ubeda, where the prior disliked him, John chose Ubeda.

John was feverish, nauseous, and unable to eat when he was carried to the Carmelite house in Ubeda. The prior put him in a drafty cell. The doorway to his room was so low that John, who was only four feet ten inches tall, had to bend to enter it. He never complained about the prior’s criticisms and petty behavior. He patiently endured a painful surgery (obviously without modern anesthesia) to remove diseased flesh from his leg. When the Carmelite provincial learned that John was being mistreated, he personally came to Ubeda to reprimand the prior, and to his credit, the prior repented.

A holy and patient death

John, however, was dying, and his final words were the words of Christ: Into your hands I commend my spirit.1 As his insightful biographer, Richard Hardy, describes it, “His death was as his life: gentle, tender, compassionate, and loving.”2

The cruel lies that were told about John hung like a foul cloud over his memory for many years. But the doctor had seen his gentleness. The friars had watched his patient, painful death. These witnesses knew that they had been in the presence of a saint, and they continued to pray for his intercession from heaven. It took eight decades for John of the Cross to be beatified and another five decades for him to be canonized.

Saint John of the Cross was a holy man, yet his holiness seems to lie in absurd contradictions. He lived in poverty, yet he did not resent being poor and even drew spiritual riches out of his suffering. Although he was small of stature and seemed too weak to endure even ordinary physical trials, he survived months of torture with his faith intact and forgave his persecutors. He possessed the sensitive soul of a poet, yet was a strong leader who could make difficult decisions. He conquered the natural human fear of suffering not by avoiding it but by offering his pain to God.

In all these ways, of course, Saint John of the Cross was merely walking in the footsteps of our Lord, who deserved to grow up in a palace but was born in a stable, who remained silent when he was falsely accused, and who became the King of Kings while being humiliated, tortured, and killed. When our own lives include experiences of rejection, cruelty, and weakness, we can, like John, turn to Jesus Christ as the cause of our joy, but also the cause of our holiness.

Or as John explained it in a collection of simple, profound sayings about the spiritual life: “Well and good if all things change, Lord God, provided we are rooted in you.”3

Endnotes:

1 Lk 23:46

2 Richard P. Hardy, John of the Cross: Man and Mystic (Washington: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 2015), 121.

3 Saint John of the Cross, The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross, Kieran Kavanaugh, OCD, and Otilio Rodriguez, OCD, trans. (Washington: Institute of Carmelite Studies Publications, 2017), 88.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply