Dr. Paul Seaton, who is a contributor to CWR, is an independent scholar whose areas of intellectual interest and specialization include political philosophy and French philosophical thought. He has translated and written extensively on modern and contemporary French political philosophers, from Alexis de Tocqueville and Benjamin Constant to Rémi Brague, Chantal Delsol, and Pierre Manent. He is the translator of Pierre Manent’s The Religion of Humanity, and author of Public Philosophy and Patriotism: Essays on the Declaration and Us (2024), both published by St. Augustine’s Press. He most recently translated Manent’s Challenging Modern Atheism and Indifference: Pascal’s Defense of the Christian Proposition, published recently by Notre Dame Press.

He corresponded recently with CWR about Manent’s new book, focusing on Pascal and what the famous French thinker has to offer to 21st-century Catholics and others.

CWR: For readers who are not familiar with Pierre Manent, can you give an introduction to his thought, work, and importance?

Paul Seaton: First of all, thank you for this opportunity to speak about this book on Pascal and its author, Pierre Manent.

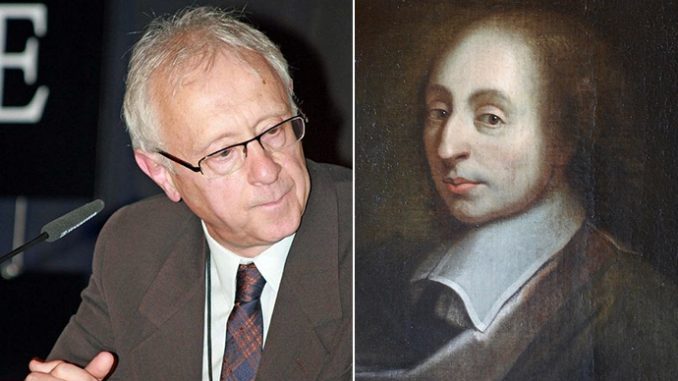

Manent, born in 1949, is France’s and Europe’s premier political philosopher. In a career now spanning over fifty years of incisive exegesis and analysis, he has tracked the origins and vicissitudes of “liberalism” and its real-world progeny, liberal democracy; revived interest in the modern nation-state in the face of its critics and the sirens of its demise; detected, named, and critiqued an ersatz democratic-humanitarian religion, the religion of Humanity, which has infected secular and clerical elites alike; and, more recently, produced original scholarship on Montaigne, natural law, and, now, Pascal.

All of this has been at the service of understanding and defending “man, the political animal” and “man, the responsible agent,” figures of the human put in the shadows by modern political theory and practice. The new book on Pascal (1623-1662) continues this set of concerns by explicating Pascal’s analysis of a dawning modern world and his attempt, on one hand, to restore the understanding of the fullness of the Christian life of repentance and conversion in the face of Jesuit laxity, and, on the other, to address arguments to modern atheists capable of stirring them from their complacency and indifference to the Christian religion.

CWR: How is this book different from most of Manent’s work?

Seaton: It is different in two fundamental ways.

First, in its subject, which is Pascal’s powerful rearticulation of the Christian faith and life in the midst of dawning modernity, characterized by a new natural science and a new form of government, the modern state.

Secondly, by its scrutiny of dimensions of human being that previous work only touched on, aspects illumined and addressed by Christianity: original sin, grace, and life with God. Ever the political philosopher, he incisively reconstructs Pascal’s view of political and social order, but adds Pascal’s provocative discussion of how a Christian should comport himself vis-à-vis the newly ordered human world. The discussion is “provocative” because Pascal locates himself between what we today call “social justice Catholics” and “integralists”.

CWR: Pascal is, on one hand, a well-known name to many Catholics, but he is also somewhat controversial because he is associated with Jansenism and has a reputation for being “dour”. Does Manent shed new light on Pascal’s thought, especially his famous “Wager”?

Seaton: Manent demonstrates that Pascal has been subject to misunderstandings and misconstruals from the beginning. He was never a Jansenist, and his personal experience and poignant descriptions of the life of fidelity to grace belie the characterization that he promoted “a sad religion,” as the famous man of letters, Leszek Kolakowski, put it. Pascal’s famous “Memorial” of an intense experience of God and His goodness one November night in 1654 continues to move the heart, and Manent ends his book with an appropriately moving “analysis” of it.

As for “the wager” (le pari), Manent’s treatment of it is one of the many highlights of the book. Its chief virtues are to emphasize Pascal’s objective in the wager, which is to put the insouciant or “libertine” reader in a certain disposition–the proper disposition–toward a unique Object, an infinite God, and a unique alternative, an eternity with or without Him; and to track the subtle rhetoric employed by Pascal as he moves the reader to that disposition and decision. As they say, this discussion is “worth the price of admission.”

CWR: How does Manent think Pascal helps in addressing 21st-century skepticism and atheism?

Seaton: I would put things this way: Manent helps Pascal make his case in ways that the 17th-century apologist could not have. That, however, does not mean that Pascal does not speak to 21st-century human beings. Pascal had an acute sense of “natural reason” fueled by “self-love,” as well as the specific determinations of “modern reason,” both of which continue to pose obstacles to the understanding and acceptance of the Christian Faith.

His various arguments were designed to expose and remove these obstacles, as well as to show properly tutored reason that Christianity not only did not violate it, but that it was truly reasonable to believe. Manent adds to this an awareness of “us” today. At any number of points, he sketches this-or-that belief “we” have concerning equality, justice, religion, etc., and then shows how Pascal’s arguments effectively respond to them. This is Manentian “value-added.”

CWR: And how do Manent’s philosophical background and his deep knowledge of France and Europe in general help in his explications and exegesis of Pascal?

Seaton: I’m glad you asked about Manent, la belle France, et l’Europe. Manent is a true son of France and a true son of Europe. Reading him is a privileged guide to France’s history and culture, and to Europe in its essential nature and vocation.

Elsewhere, I have written about his analyses of Europe’s nature and vocation and how and why Europe has abandoned its heritage (an analysis that closely tracks with Benedict XVI’s). At the beginning of the Pascal book, Manent recalls the essential role that Catholic Christianity played in the formation of Europe, in the psychic dynamics of Europeans, and contrasts it with today’s jettisoning of its founding faith and enforced secularism.

Then, in a bold move that is at once countercultural and deeply faithful to European culture, he declares that his purpose in this book is to “repropose,” with Pascal’s help, this faith in its challenging integrity. I find this to be a model for all Catholic Europeans today.

CWR: You write, in your Introduction to the book, that while you’ve translated many books, including some others by Manent, “none has touched me or moved me the way that this book has.” Can you reflect and explain that a bit?

Seaton: I am very much a political animal. Manent’s political philosophical analyses have helped me enormously as I try to understand the Western world, especially in its post-Cold War “structure and dynamics.” In so doing, he has both fueled and directed my thumos or righteous indignation against the enemies of liberal democracy, the nation-state, and Western civilization.

But with the Pascal book, he “reminded” me that I am a Christian and that I need to attend to my soul. While this book has brilliant analyses that appeal to the intellect, it also has passages that deeply touch the heart and cause one–me–to pause, to ponder, and to pray.

CWR: The “indifference” aspect of the book and its focus are important. How does Manent describe, explain, and address it?

Seaton: A splendid question! Pascal and Manent constantly operate on two levels: the level of human nature after the Fall, and the level of dawning modernity and its aim to form a new kind of human being, one satisfied with the world, and proud of his freedom and power.

The analysis of “indifference” or “insouciance” therefore operates on two levels or registers. The regular pattern of the book is to cite Pascal on this-or-that quality of being human–in this case human “indifference” to the Christian proposition, or even to one’s unavoidable death—then for Manent to explain and illustrate it. Pascal constantly calls his reader to the reality of his situation, be it his mortality or his disproportionate attention to slights and games rather than his inescapable fate.

But what is most striking in Manent’s reconstruction is the recognition that Pascal does not aim to fully awaken his reader with these exposés. Rather, he wants the reader to see his, at best, half-awareness, which confirms the Christian teaching of man’s inescapable bondage and need for a Liberator.

CWR: You also note that Manent builds upon Pascal’s argument(s). What is an example of this?

Seaton: Above, I indicated in a general way Manent’s “value-added”: he articulates contemporary attitudes and serves as a middleman to Pascal and the contemporary reader. To this, I would add the following. Manent can look back at Pascal and provide a sure and illuminating exegesis of his texts and thought. But because he writes from the 21st century, he can also contextualize Pascal and “read him backward and forward,” as it were. These contexts include predecessors such as Machiavelli and Montaigne, Luther and Calvin, contemporaries such as Hobbes, and later philosophical interlocutors such as Voltaire and Rousseau.

What Manent does is put Pascal in the context of “modernity,” with its aim and addiction to “Progress,” and the various “vectors” that constitute it, including a narrowing of “the domain of commands” and an expansion of “the domain of freedom.” This is not eisegesis (a practice and vice I hate). The Jesuit laxity exposed by Pascal in The Provincial Letters unintentionally but historically took its place in a wider modern endeavor to dissolve the dictates of conscience and, as Nietzsche wrote and Manent cites, “to loosen the bow of the European spirit.”

CWR: Any further thoughts?

Seaton: Translating is a privilege, it is a privilege because one spends “quality time” with a mind superior to one’s own, it is also a privilege because it makes available the penetrating thoughts and elevated sentiments of a foreign mind and soul that the recipient audience may not be in a position to know. In my case, it is also part of a vocation to serve God and His Church. My hope is that this book enlightens the intellect and moves the heart of its readers. It certainly did both with me.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Oct 3 2025

🇺🇲

When will I see the Catholic Church, and the Pope, and the Cardinals all condemning the horrific Genocidal Holocaust against innocent defenseless minor Palestinian children and unarmed civilians in Gaza?

And

condemning our government’s complicity by supplying the weapons of mass-destruction and Felony-Straw-Guns to the idf?

Oh dear God Almighty please forgive our wretchedness and our failure to act in the face of such evil beyond hitler 😪🤲

“… in the face of such evil beyond hitler [sic].” And you really expect people to take you seriously?

Timothy: “beyond Hitler”aside, let’s not make light of the plight of the Palestinians. Don’t throw out the baby with the bath!

Well, if you are so concerned, what are you doing to actually help those in need, other than lecturing the rest of us?

Supporting NEWA , for starters! and you?r.

A bit histrionic for a man, wouldn’t you say?

Well, that’s easy. There is no “holocaust” taking place in Gaza. The Palestinians are simply reaping what they have sown, rightly so. When you choose the behavior, you also choose the consequences of that behavior.

This is a most-welcome book. When I was in graduate school studying and writing on Pascal, I was practically berated for maintaining that he was no Jansenist, despite his abhorrence of Jesuit laxity. But then, back in the 1980s, it was über chic to maintain that Pascal never intended to write an apology of the Catholic Faith! Academics will do anything to avoid considering the important and obvious questions.

The interview discusses many things that remain in the background. It was Jansenism that was declared to be the heresy not “Jesuit laxity” of that time. Jansenism had attacked “Jesuit laxity” of that time in a way that is rooted in the Jansenist heresy. Once the heresy was declared, Jansenists made to distinguish themselves from what was declared. There are many confusions going on in and around Jansenism. Pascal was the committed “apologist” in all of it, his activity served for repurposing. Repurpose.

Or, “re-propose”. It could additionally be demonstrated that the “re-proposing” was an exercise in drawing forth the “eminent sense” and “Augustinian merit” in the “Port Royal community and outlook” -Jansenism.

In which case the book is an admission.

The indifference or insouciance to history showing HERE would actually fit right to the confusions that comes with Jansenism. Now I haven’t read the book, but Seaton seems to admit what it is that it means to be doing when he says -which he actually does say:

‘ … I indicated in a general way Manent’s “value-added”: he articulates contemporary attitudes and serves as a middleman to Pascal and the contemporary reader. To this, I would add the following. Manent can look back at Pascal and provide a sure and illuminating exegesis of his texts and thought. But because he writes from the 21st century, he can also contextualize Pascal and “read him backward and forward,” … ‘

I am not a scholar. Not good enough CWR.

A true son of France and a true son of Europe reveals Seaton’s Francophilism. This does not dismiss the important influence of France on culture in Europe and in general, although it may indicate a more subjective than objective critique of Manent’s description of Pascal.

Although “Natural reason fueled by self-love” is a strong affirmation of Seaton’s critique, underlining a major premise of a Religion of Humanity. Certainly a premise that has taken hold of Catholicism at this time. “Human indifference to the Christian proposition”, a state of satisfaction with the world as is. Jesuit laxism and a host of philosophers are named as culpable, probably the most significant Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

For those interested in an in depth review of trends of thought that lead to where we’re at today Seaton’s book, although it’s not clear to this writer which translation and commentary of Manent by Seaton – is well recommended.

France: The inventor of pre-emptive surrender.

Also, the first place that required a state issued marriage license.

It’s true that Islam won’t be integrated into the the modern state in the West, with all the consequences that ensue. Manent is involved in these debates. He’s mistaken, however, in defending the modern state in the first place. The modern state became hegemonic around 1700, by overcoming the last, Baroque, phase of the traditional Christian West. The modern state, by definition, makes civil society an absolute, and the final arbiter of whether to recognise natural or divine law. This does not sit well with Islam, but is even more incompatible with the old Christian West. If we’re going to sort out such problems, we have to revisit the notion of the modern state itself.

The primacy of the state was concocted in the minds of theological opponents, Henry Tudor and Martin Luther. This was excised from another site today.

“Marriage is a civic matter. It is really not, together with all its circumstances, the business of the church.”

“What Luther Says” CPH 1959, Vol. II, page 885)

“I feel that judgments about marriages belong to the jurists. Since they make judgments concerning fathers, mothers, children, and servants, why shouldn’t they also make decisions about the life of married people?

LW Vol. 54 page 66)

The state tells you that a woman can leave her husband for any reason or none at all, and he will be obligated by the force of law to maintain her in a separate residence-at the same time it tells me that I must submit to its declarations that two people of the same sex are married.

And I might note, that Henry Tudor-not for the sake of theological novelty-but the satisfaction of his baser urges-and despite meting out his mass murderous rage on Lutherans as well as Catholics also subordinated marriage to the state.

I assume both had to answer for rendering to Caesar what is God’s.

Innocent X condemned Jansenism by apostolic constitution no less, Cum occasione, in the form of the papal bull.

Jansenists then set about distinguishing what it could mean while they remained Jansenist; and Pascal persisted as if nothing had just happened.

Now then: is there one account of a Jansenist renouncing the community and heresy and embracing the apostolic constitution, transferring obedience to the Pope?

https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_letters/documents/20230619-sublimitas-et-miseria-hominis.html.

Where is the Jansenist convert.