“My theme is memory, that winged host that soared about me one grey morning of wartime,” says Captain Charles Ryder in Evelyn Waugh’s novel, Brideshead Revisited. “These memories, which are my life—for we possess nothing certain except the past—were always with me,” he continued.

Brideshead is a fictional exercise in what one might call an Augustinian memoir. Its implicit allusions to St. Augustine’s Confessions are found both in the form of the story and in the details of the spiritual pilgrimage of Capt. Ryder, the protagonist and first-person narrator of the novel. Waugh’s Ryder reconstructs the narrative of his own life through a theological interpretation of his relationship with the Flyte family, who constitute an imperfect example of the flawed people who constitute the perfect society of the Church. For Waugh, the use of memory is not to invoke treacly nostalgia for some imaginary better past, but rather to find—or perhaps impose—coherence on the fragments of Ryder’s life. Thus, memory serves the function of ordering Ryder’s life toward resolution. From bits and pieces emerge a coherent story; from random “facts” a deliberate, purposeful life.

Constitutional memory

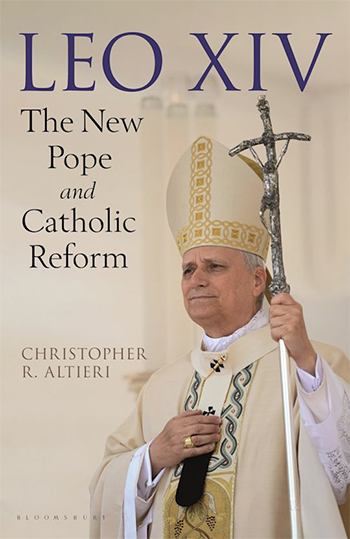

I often thought of this passage from Brideshead as I read Christopher R. Altieri’s wonderful new book, Leo XIV: The New Pope and Catholic Reform.

Situating Pope Leo’s pontificate in his Augustinian formation, Altieri has a keen ear for Leo’s nuanced interpretation of his role as Supreme Pontiff, firmly rooted in the tradition of ecclesia semper reformanda. “For the Augustinian,” Altieri explains, “memory is not merely a storehouse of the past but the threefold presence of all time: a power of the mind to make present the past, yes, but also the presence of the present and the presence of the future” (p. 117).

For the Augustinian, therefore, memory “is not … primarily a power of mere factual and procedural recall—though it is that—but the power that keeps our origin in God before us,” continues Altieri. Memory, one might say, consolidates the reditus and exitus into a coherent account of the now.

Thus, Altieri highlights Pope Leo’s May 24, 2025, admonition to employees of the Holy See: “Memory is an essential element in a living organism. It is not only directed to the past, but nourishes the present and guides the future.”

“Without memory,” Leo continues, the Church loses its sense of direction. “The path is lost.” This “monumentally significant” statement by Pope Leo, contends Altieri, expresses the “mode of communion-in-memory and communion-as-memory that unites the whole Church through all time and into eternity” (pp. 117-118).

Communication and community

A couple of caveats are in order.

First, Christopher Altieri is a frequent and long-time contributor to Catholic World Report and a friend of both the editor and this reviewer. This has no importance for my review of the book, but readers should be aware, nonetheless.

As a long-time, formerly Rome-based journalist, Altieri is one of the two or three sharpest-eyed American Vaticanistas. As such, his acute observations about the place of Leo XIV in recent papal history carry substantial weight and are worthy of careful consideration, without regard to where they are published or by whom they are critiqued.

The second caveat is that Pope Leo XIV is not—as it is not intended to be—a biography of the new Pontiff. Of course, key details of his life are recounted along the way. But the focus of the book is the See of Peter itself, in the context of the early weeks and months of its current occupant. This is not to say that Pope Leo XIV is incidental to Altieri’s thesis. On the contrary, by focusing on Leo’s Augustinian formation, Altieri is able to situate Leo squarely within a hopeful account of the current crises and perpetual hope that always accompanies any consideration of the ecclesia militans.

Put another way, Altieri’s purpose is to explore the hope of the current Pope in the historical, theological, and ecclesiastical context of the turbulent history of the Church, including specific crises that must be addressed in the very near future. Altieri understands that Pope Leo faces challenging tasks in the wake of the less-than-successful pontificate of his immediate predecessor. “The conclave that elected Pope Leo XIV was not so much a referendum on his predecessor,” he writes, “as it was an acknowledgment of the good and the ill of the Francis pontificate.”

The electors were neither looking to repudiate nor perpetuate Francis’s agenda. Rather, “[t]hey were looking for someone with a fighting chance at bringing peace to the Church: order to her affairs and justice to her people” (p. 52). While Altieri approaches the problem with a light touch, the shortcomings and missteps of the prior papacy are inescapable as one reads his catalogue of the challenges that face Leo.

Sustained by narrative continuity

My own discernment of a theme in Altieri’s fine book is two-fold.

First, he understands that one cannot fully appreciate Leo’s approach to his office apart from St. Augustine of Hippo, especially The City of God and Confessions. From the former, Altieri’s Augustine-formed-Leo takes very seriously the strange citizenship of members of the Civitas Dei as we toil in this Civitas Terrena. “‘All of us, in the course of our lives, can find ourselves … living in our native land or in a foreign country,’”

Altieri quotes Leo from his May 16, 2025, speech to accredited diplomats to the Holy See. This reflects the Augustinian notion that humans are “being[s] in motion, exiled from our true home in the celestial Jerusalem and existentially either mostly on the way there as pilgrims or else mostly wandering about as vagabonds” (p. 66). Pope Leo seems to have a strong sense of the peregrinations of human existence and the place of the Church in discovering order in those wanderings.

Second, Altieri understands the importance of communication for a successful Leonine pontificate. From St. Augustine, Pope Leo has a keen sense of the necessary role of continued truthful discourse to sustain the truthful community of the Church. Thus, he spends a good chunk of the book discussing the importance of truthful, transparent, and humble confession, both of the failure of conventional ecclesiastical institutions and the supernatural sustenance of the Barque of Peter. Pope Leo, Altieri explains, “has been thinking about the nexus of communion and communication, communio and communicatio” throughout his priestly career (p. 79).

Thus, Altieri is hopeful that Pope Leo XIV can “repair[] the broken communications culture in the Vatican.” This task is “mission-critical because the Church’s whole purpose is to communicate the Good News of salvation to the whole world” (p. 104). This is not mere public relations. Rather, quoting Leo, “‘[w]e have a duty to work together to develop a language, of our time, that gives voice to Love’” (p. 165, quoting the pope’s 29 July 2025 address to “Catholic digital missionaries and influencers”).

As both Altieri and Pope Leo XIV know very well, we already have the vocabulary and grammar of such a language. Thus, we do not invent but rather develop that language in a way that takes seriously the signs of the times, but never abstracts them from the continuity of Christ’s promise to his Church.

In other words, as Altieri points out, concrete reform and regulation are of critical importance. This includes improvement in the financial, juridical, and communicative offices of the Holy See, which, not to put too fine a point on it, are in urgent need of renewal and reformation after years of less than successful oversight.

This is not a task for the pope alone, as Leo himself cautions us. “We have a duty to work together,” he said in the July 29th address. Put another way, Pope Leo might be uniquely situated to revive a synodal way of being Church without succumbing to the nebulous concept of Synodality that has vexed the Church over the past several years.

To understand the depth of the issues and why Leo might be the perfect man for the job, the reader can do no better than to take up and read Christopher Alieri’s insightful and engaging book, Pope Leo XIV: The New Pope and Catholic Reform.

Leo XIV: The New Pope and Catholic Reform

By Christopher R. Altieri

Bloomsbury Continuum, 2025

Hardcover, 212 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

The first move toward a successful Leonine pontificate would be rescinding the use of the word “synodality.” It is a term that harbors within it all the accretions of the Bergoglian Papacy and immediately shuts down dialogue. Find some other word that ALL the faithful can comprehend and get behind. If you want transparency, then one needs to use terms that are easily comprehensible.

Benedict’s term, already forty years ago, is “ecclesial assembly.” No confusion with or even gradualist replacement of the distinct synods of bishops within the Apostolic Succession as a “hierarchical communion” (Lumen Gentium).

Right now, Leo isn’t a copy of Francis, but maybe a mimeograph.

If Leo XIV has a grand strategy of reconciling a divided Church due to Francis the First’s ham fisted rough handling, it’s yet to be revealed in Pope Leo’s more gentle velvet glove approach.

Memory is Augustine’s ‘the power that keeps our origin in God before us’. It’s an enormous task of rectification as well as communication. Not to recognize the former already foretells a losing effort. And a ‘cementing of Francis’ unacceptable ‘novelties’.

We have the grammar to transmit the voice of love. But do we have the heart to speak the truth? Example. We no longer hear the Word’s admonition to sin no more, to repent, and to convert. If Leo XIV can succeed in forming a faithful community meaning one faith one baptism in this divided ecclesial condition we’re in then all the world’s blessing upon him.

Father, it seems to me that courage is a virtue long buried by the papacy. The clear voice that once declared God’s love, identified and condemned the sins of the world, and extended the invitation to repentance seems lost. Popes appear hesitant, fearing they might offend sinners, and as a result, fail to point out the righteous path back to our Father in Heaven. It’s a disheartening state, unable to inspire the hope found in Christ. The Church, under the pope’s guidance, stands on the sidelines, leaving the work of the Gospel to others.

We must be patient, prayerful and supportive. Change will take time and will require openness and charity. If we expect others to change we must be willing to change as well. The Pope has one of the hardest jobs on earth and he is only a mere mortal and he will make mistakes. We must be sure to support him as much as we can and be slow to criticize. He IS our Pope!

A delight to read about the Augustinian perspective of Pope Leo XIV. Our times are very much like Augustine’s when the Eternal City was sacked by Alaric in 410 A.D. About that catastrophe, the shepherd Augustine sermonized this to his flock in North Africa:

“This is grievous news, but let us remember if it’s happened, then God willed it; that men build cities and men destroy cities, that there’s also the City of God and that’s where we belong.” He then spent thirteen years reflecting and elaborating, in “The City of God,” on the reality and meaning of the Incarnation…as compared to the backwardist (!) pagan ideologies still lingering in the empire of his day.

In our own time of internal chaos and external fantasies, we now look forward to more reflection and elaboration from Leo on the irreducible DIFFERENCE between invertebrate tendencies within “synodality”—as an “attitude” and “a way of ‘being’ the Church”—and what Pope Benedict clarified when he also wrote that even a council (or synod!) is only what the “does” and not quite what the perennial Church “is.”

Too many things that “go without saying,” today need to be said. For example, about the universal (not synodal) Natural Law: “the Church is no way the author or the arbiter of this [moral] norm” (St. John Paul II, Veritatis Splendor, n. 95).

SUMMARY: As a luminary in the secular Oval Office once pontificated: “it all depends on what the meaning of the word is, is.”

https://bigmodernism.substack.com/p/the-synodal-seance-when-truth-becomes?publication_id=4940692&utm_campaign=email-post-title&r=4d8ftt&utm_medium=email