Among his (temporarily?) abandoned liturgical instructions that generated a firestorm of controversy recently, Charlotte Bishop Michael Martin wanted to suppress the pre-Vatican II practice of praying vesting prayers while putting on vestments for Mass. Upon reading about it, my initial reaction was one of surprise: first, that priests were still using those prayers, and second, that a bishop had a problem with it. It inspired me to write in Adoremus about the evolution of Mass vestments and those prayers.

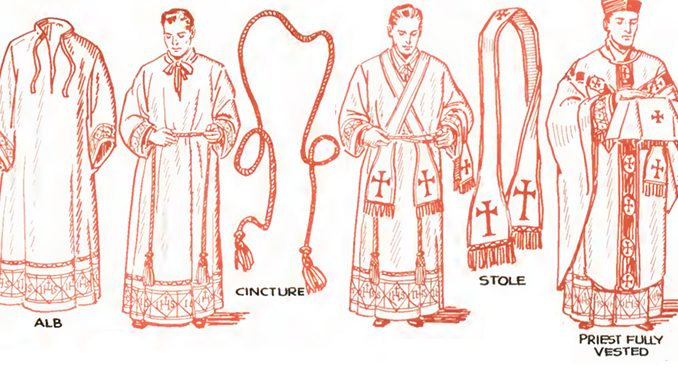

I argued that the principal vestments used at Mass—amice, alb, cincture, stole, chasuble—originated as non-upper-class common garments in the time of the early Church. The Church used them, often with the stipulation that clergy have a special set–their “Sunday best”–exclusively for use during the liturgy. When fashions changed, primarily thanks to the fur-clad invaders from Germania in the fifth and subsequent centuries, the Church retained those earlier garments which, now by virtue of their uniqueness, had in some sense become “sacralized”.

If cinctures and chasubles passed out of daily dress and became sacralized, one should not be surprised that sacred meanings came to be associated with them. Chasubles were originally the equivalent of protective outer gear. When they ceased being that, even though they continued in use, they would need a new meaning. That meaning came to be associated with putting on the “yoke of Christ” upon one’s shoulders, both heavy (the traditional Roman chasuble was a large and weighty garment, especially after Baroque designers got a hold of it, which is why the trimmed “fiddleback” became popular).

The point is that, having retained what had become anachronistic fashion, one had to explain why. The explanation eventually came by attributing religious and mystical meanings to them. It’s not unlike Scripture, which starts with a literal meaning and eventually acquires a mystical one. Without this “mystification,” retaining these garments as liturgical wear would have been an ecclesiastical version of cosplay.

And that’s what’s important here: they are not decorations or play. Their new lease on life came from new meanings given to them, meanings which the old Latin Rite vesting prayers (and current vesting prayers in the Eastern Churches, both in and out of communion with Rome) express. And the primary character of those meanings is moral.

Aimé-Georges Martimort, in his masterful work The Church at Prayer: Principles of the Liturgy, makes the point that the core function of the liturgy is to make us holy through our worship of Him who is Thrice-Holy. It’s not about “community formation,” aesthetics, or even just proper liturgical form. All of those are important, but they are quite secondary to the central truth: the liturgy presupposes holiness and seeks to make us holy. And since holiness in the true Jewish and Christian traditions is not mere ritual but moral rectitude before God and neighbor, a focus on moral readiness seems to be appropriate to the immediate preparation for celebrating the liturgy using those vestments. That mirrors the priority of the Mass itself: immediately after our Trinitarian acknowledgement and greeting, our first order of business is “to prepare ourselves to celebrate these sacred mysteries by calling to mind our sins,”—that is, by turning from what makes us unworthy to celebrate liturgy.

The focus of the vesting prayers was very much on moral uprightness. Consider that current Eastern vesting prayers begin with washing one’s hands and prayer, not unlike the washing of hands during the offertory. “Being clean” is not just a utilitarian, hygienic standard. As Karol Wojtyła noted in an early article, “The Religious Significance of Chastity,” “purifying” and “purity” were also associated with an awareness of the moral uprightness we should have, as well as making us conscious of our deficiencies in that regard.

The prayers, of course, followed the order of putting on vestments (amice, alb, cincture, stole, chasuble), which followed their layers from inside out. The prayers for two vestments—ones often unused—particularly stand out: the amice and cincture.

The amice is a kind of head covering that the priest momentarily places on his head before lowering it and wearing it on his shoulders. The prayer accompanying the putting on of the amice speaks of thoughts: of pure thoughts elevated to God, of impure thoughts, vanities, and earthly priorities put away. The priest prayed for a “helmet of salvation” that would protect him against the assaults of the devil.

The cincture is a white rope around the waist. Its use was to regulate the length of the alb, especially when parishes didn’t have a variety of short-medium-tall sizes. Encircling the waist, the prayer accompanying the tying of the cincture in place alluded to what is below the waist: more earthly passions and desires. While vesting with the cincture, the priest prayed to “extinguish in my loins the desire of lust” while cherishing the virtues of chastity and continence.

Controlling one’s sexual urges and raising one’s mind to God—aren’t these two central spiritual motivations we should want in our clergy, deficiencies whose lack has cost us, spiritually and financially, in the sexual abuse crisis? Besides bringing back amices and cinctures in the many places they have fallen into disuse, might we not also consider the prayers that accompanied them?

The alb–a long, white gown–also alluded to purity, purity akin to Christ the High Priest, whose seamless priestly tunic is among the garments the Gospel of John specifically names and for which even the pagan Roman soldiers had enough respect to gamble over rather than rip? A prayer for a “purified heart” made “white in the Blood of the Lamb” should remind the priest in donning the alb that, even (especially?) in the Novus Ordo, it’s not about him but about Him whose alter Christus he is?

The stole is a sign of the clerical office. It’s why the East has a different style for the diaconal and sacerdotal stoles. It’s why in the West the manner of its wear distinguished its wearer: over the shoulder for deacons, over the shoulders crossed at the breast for priests, over the shoulders hanging straight for bishops. (Bishop Martin took exception to priests crossing the stole over their hearts.) The priest prays for the restoration of the “joys of immortality” lost through sin so that “as I draw near to Your sacred mystery, may I be found worthy of everlasting joy.”

Finally, the chasuble. As noted above, what was an ample protecting outer garment became a symbol of Christ’s “yoke.” Yokes are heavy, and chasubles were heavy, too, especially when richly ornamented or in pre-air conditioning churches during the summer. The yoke of priesthood is heavy, whether it be lifestyle sacrifices or simply the multiplicity of duties intensified by a lack of priests. But, as much of a yoke as it might be, the priest should approach yokes with the eyes of faith: “My yoke is easy and my burden light” (Mt 11:29-30).

No doubt, for some priests, the old vesting prayers might have become rote ritual. That is not an argument against them but against the one “praying” the prayers. But for the priest who did consider what he was praying, the vesting prayers were a daily reminder (assuming the priest celebrated Mass daily) of certain basic moral truths that should have shaped his priestly identity and spirituality.

One also suspects the vesting prayers would help shape overall preparation for Mass in a more spiritual direction. If, in an earlier time, the vesting prayers were recited in the priest’s sacristy while the altar boys did their thing in the altar boy’s sacristy, the absence of vesting prayers in our day seems to mirror what is perhaps the imbalance in the modern sacristy: a lot of movement (especially for ritual details, e.g., candle lighting and book placements), some small time (to fill the airtime), and little prayer.

Recovering that sense of the sacred will not happen just from external forms, but I do not believe that is what those priests who resurfaced these prayers had in mind. That a new generation of priests rediscovered the old vesting prayers does not necessarily mean there is some traditionalist fifth column waiting for the moment to celebrate like it is 1959 again. A “synodal” listening Church might ask whether the phenomenon points to some lacuna those priests sense in “the way things are” and how that gap might be filled–by things new or old, a readiness to visit the storehouse (Mt 13:52) not out of nostalgia but out of need.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Thank you so much. I thought those illustrations looked familiar.

🙂

My Catholic Faith is my go-to Catechism book. I have a slightly later edition from the mid 1950s. It’s a wonderful resource.

I have one too and love it for its clarity.

Grondelski makes a good point citing Aimé-Georges Martimort, that the liturgy is to make us holy rather than entirely focused on community formation. Although when the priest becomes holy that holiness becomes manifest in the liturgy having salutary effect within the community.

After ordination the first item that slowly disappeared was the amice. Next the cincture. Now many priests simply wear a glorified alb and stole. The pattern was contagious until a friend passed on a couple of the old fiddleback chasubles. Although these were heavily, beautifully embroidered. I wore them on feast days, solemnities starting using rope cinctures again.

External form as Grondelski alludes doesn’t necessarily affect Holiness. Although it certainly is conducive to a deeper appreciation of the entire spectrum of meaning attached to offering the sacrifice of the Mass.

Actually the fiddleback was simply much lighter, not too embellished. The draping front and back chasuble is the Roman chasuble. The chasubles given me were much heavier, highly embroidered Roman kind.

The other similarly embroidered chasuble more like a full tunic is called the Gothic chasuble. They’re also beautiful although not as heavy and as fully embroidered. The masterpiece example of liturgical art in vestments is the Roman chasuble.

Form without content is usually useless, agreed. But it seems that, without prayers, our cosplay form is empty.

Thank you for the interesting information. Our priest dresses right next to the main entrance but there are doors he can close if he chooses. The altar servers dress up front and come back with the processional cross.

He clearly is dressing “special.” Unlike the ancient Church, these garments are not the typical everyday wear, and our clergy don’t dress in modern, everyday “wear” for Mass. So, it’s more than “dressing,” and that suggests it should be more than just the utilitarian task of putting on some old clothes.

John,

Thanks for this article. Great reminder of who the clergy are… we can learn about who the priest is by learning about their vestments.

One vestment was unmentioned: the maniple. When I heard about the bishop who wept at his first offering of the Usus Antiquior, the maniple becomes not only liturgically and spiritually meaningful, but quite necessary.

Young people are especially interested in these ancient signs of who the priest is ontologically.

So many of us younger Catholics are thirsting for knowing these lost truths that were never formally taught in Catholic School or anywhere in the last 60 years.

Thanks again, John.

The weeping of the bishop relates to the priest’s prayer while donning the maniple: “May I be worthy O Lord, so to bear the maniple of tears and sorrow, that with joy I may receive the reward of my labour.”

In olden times and from the pews, the vestments used to serve as drawing attention not to the consecrating priest himself, but as acting in persona Christi. By some strange inversion, the untutored in the pews now see the vestments as decorations for their buddy, Bishop Joseph or maybe Fr. Joe, and possibly Fr.(?) Josephine. Very synodal, that.

Yves Congar described Sacred Tradition as onion rings: strip them down and you are not “back to basics” but left with nothing. Post-Conciliarism is busy proving him right.

Hierarchy excepted, we’re all traditionalists now ?

Ps: Great piece Mr Grondelski.

Thanks so much for this article! Thanks, too, for the “Correction”, the addition of the maniple, which was not mentioned in the earliest part of the article. I always liked the maniple, which I understood to be one of the earliest required in the Latin Rite, having been given by a Pope to his sub-deacons in Rome. It reminds me of the towel worn over the forearm by waiters in classier restaurants when I was a kid, and underscored the “servant” nature of Priesthood. I am also quite certain that it was made OPTIONAL after the changes, but NEVER suppressed. But it was often made too short when produced by Vestment companies, and consequently became a problem since it tended to sweep things (like chalices, patens and linens) off the altar, rather than simply lying on the mensa and hanging over it, its weight enabling it to “stay put” and not move things around it.